Researchers sifting through data collected by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft during a close flyby of Jupiter’s moon Europa in 1997 have found evidence the probe flew through a water vapour plume spewing from the fractured surface of the icy world. The data are consistent with earlier indications of a plume in pictures taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

“Today’s announcement of yet more evidence of plumes jetting out of Europa are an outstanding leap forward in our search for life and habitable environments in the solar system,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s science chief, said after a 5 May news briefing.

“There were hints of plumes in the past from the Hubble Space Telescope and today’s finding … gives us further evidence to sink our scientific teeth into.”

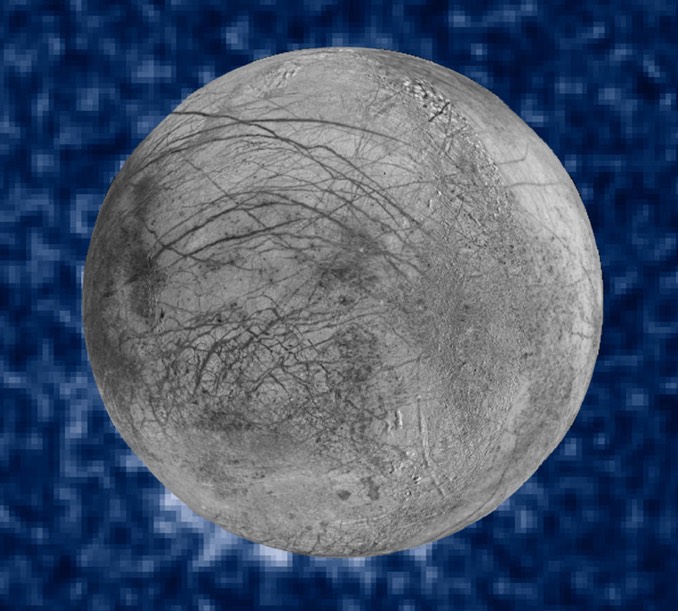

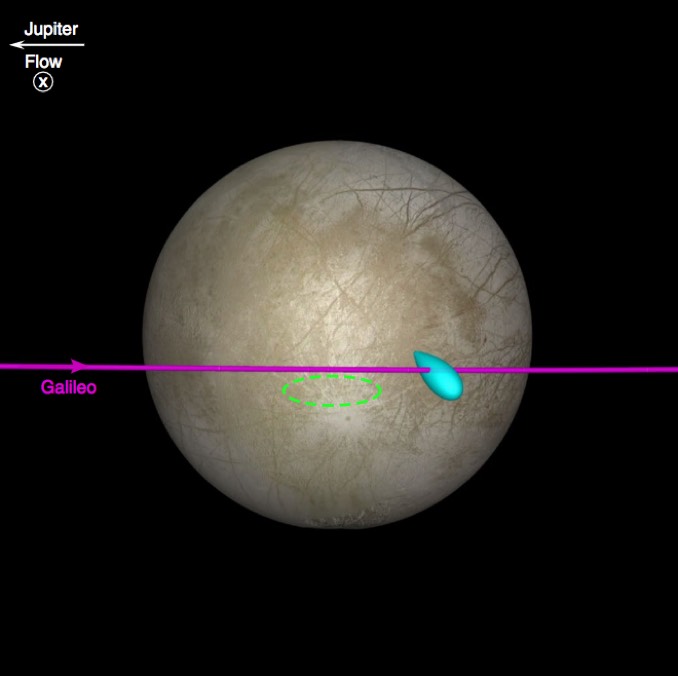

In both cases, the plumes appeared to originate at or near a known “hot spot” on the surface of Europa and likely represent, many believe, salty water making its way up from a vast sub-surface ocean hidden beneath Europa’s icy crust.

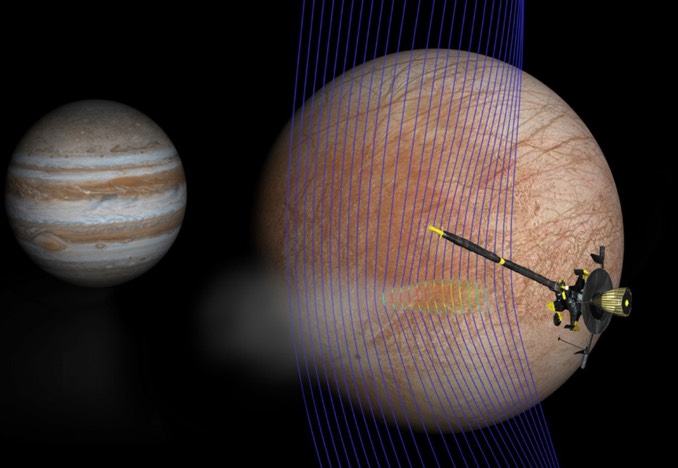

Xianzhe Jia, an associate professor at the University of Michigan who led the team that re-assessed the Galileo data, said the location, duration and variations seen in the spacecraft’s magnetometer and plasma wave data are consistent with the presumed plume seen by Hubble.

“These results provide strong independent evidence of the presence of plumes at Europa,” he concluded in a paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Not everyone is convinced. Mike Brown, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in a tweet he is a “big Europa fan,” but “so far, all of the evidence for plumes on Europa has been hopeful, rather than truly convincing. I’d love there to be plumes, but I think we should all retain a healthier skepticism here.”

Others found the evidence more compelling. Morgan Cable, an astrochemist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Scientific American magazine that “up until this paper, I was very skeptical the plume existed. … But this has made me a believer.”

Launched in 1989, Galileo braked into orbit around Jupiter in 1995. Over the next eight years, the nuclear-powered orbiter trained its cameras and other instruments on Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere and its many moons, focusing on volcanic Io and the three other Galilean moons, Europa, Callisto and Ganymede.

Observations of Europa by NASA’s earlier Voyager probes revealed a fractured surface that could be explained by a layer of warmer ice or liquid water below the surface and the action of tidal stresses imposed by Jupiter’s gravity.

During Galileo’s flybys of Europa, magnetic field data indicated the possible presence of a sub-surface salt water sea. In 2015 and 2016, the Hubble Space Telescope imaged what appeared to be a plume on the moon’s limb, although the observation was at the limit of detectability.

The Galileo magnetometer and plasma wave charged particle data studied by Jia and his team were more conclusive.

“The material that is coming out from Europa is probably electrically neutral, it’s probably dominated by water vapour,” said Margaret Kivelson, professor emerita of Space Physics at the University of California who led the Galileo magnetometer team. “But there are lots of energetic particles in the environment of Europa and they ionise the material, so they make it an electrically charged.

“And it’s those electrically charged parts of the plume that cause the changes in the magnetic field and change the density of the electrons in the environment that were measured by the plasma wave instrument. So it’s not a direct effect on the environment from the plume, it’s a two-step process.”

Both NASA and the European Space Agency are building spacecraft to study Europa and the jovian environment in unprecedented detail. Robert Pappalardo, project scientist for NAA’s Europa Clipper project, said “there now seems to be too many lines of evidence to dismiss plumes at Europa.”

“This result makes the plumes seem to be much more real and, for me, is a tipping point,” he said. If future spacecraft “can directly sample what’s coming from the interior of Europa, then we can more easily get at whether Europa has the ingredients for life. That’s what the mission is after. That’s the big picture.”