A sequence of images captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft last month are the most detailed pictures ever taken of Saturn’s famous rings, revealing complex, unexplained bands and the movements of dozens of tiny icy moonlets spinning around the planet.

In its final year of operation, Cassini is now in a “ring-grazing” orbit around the gas giant, zipping just outside Saturn’s outer F ring at an average distance of 57,000 miles (91,000 kilometers) from its cloud tops, and yielding the mission’s best views of the bands of icy particles encircling the planet.

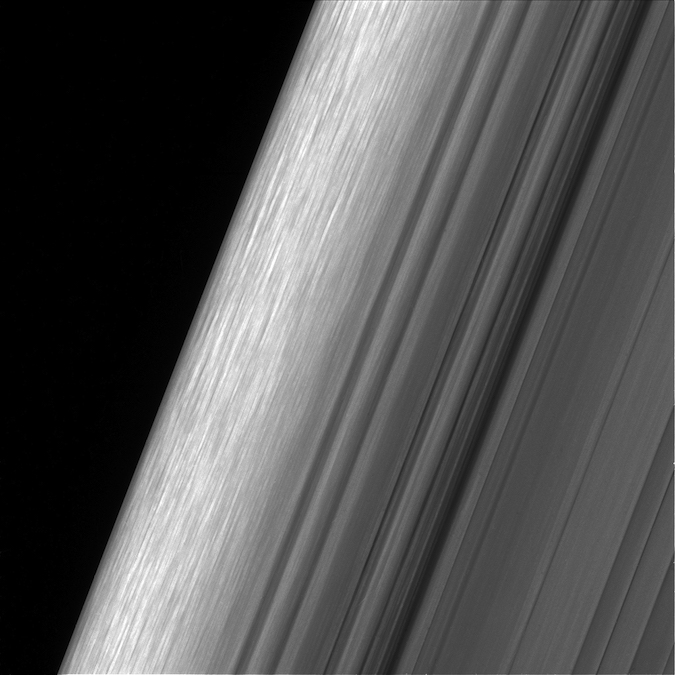

Images released Monday show the intricacies of Saturn’s rings, such as thin pinwheel-like striations in the wide inner B ring that scientists believe could be clumps of icy debris formed by the moon Mimas’s gravitational influence.

Mimas orbits in resonance with the outer boundary of the B ring, taking twice as long to go around Saturn as the material making up the ring’s edge. Scientists have dubbed the features spotted there as “straw.”

Elsewhere in the B ring — Saturn’s largest and brightest ring, yet still estimated at just 30 feet (10 meters) thick — Cassini’s camera showed countless discontinuous stripes appearing like the strands of a harp at twice the level of detail previously available.

“Researchers have yet to determine what generated the rich structure seen in this view, but they hope detailed images like this will help them unravel the mystery,” NASA wrote in a caption accompanying the image release.

Farther from Saturn, the A ring harbors more marvels and mysteries.

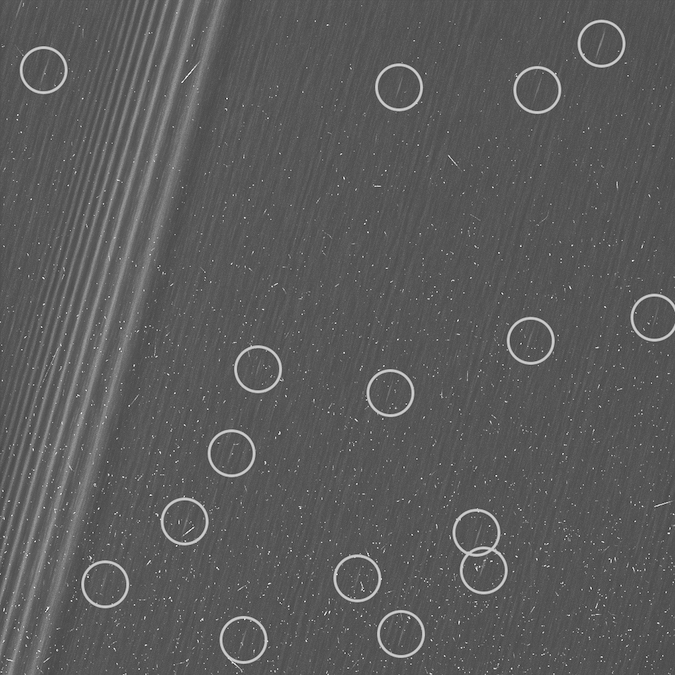

In one image of the A ring, scientists identified at least 16 smeared features they have named “propellers.”

“The view shows a section of the A ring known to researchers for hosting belts of propellers — bright, narrow, propeller-shaped disturbances in the ring produced by the gravity of unseen embedded moonlets,” the caption of one of the A ring images reads.

At the left side of the picture, scientists wrote, a density wave is visible, created by a gravitational interaction with the moon Prometheus. Such waves are build-ups of icy debris arranged in winding patterns around the planet like the arms of a spiral galaxy.

Another density wave generated by the influence of the moons Janus and Epimetheus, which share the same orbit around Saturn, is visible in a second Cassini image of the A ring. More cluttered “straw” also appears in the A ring, along with wakes from a recent passage of the ring moon Pan, according to NASA.

Saturn’s rings named alphabetically in the order of their discovery.

The images released Monday were taken Dec. 18 as Cassini crossed Saturn’s ring plane on its third “ring-grazing” orbit since a Nov. 30 gravity assist from the moon Titan pushed the probe on its current course.

Cassini’s ring-grazing orbit puts the spacecraft in the plane of Saturn’s rings about once a week, giving scientists their best views of the rings since the spacecraft arrived in orbit around the planet in 2004. During its first approach by Saturn for the mission’s critical orbit insertion burn, Cassini got a little closer to the rings, but the pictures produced in that encounter only showed the backlit side of the rings, and the images were darker and grainy.

“As the person who planned those initial orbit-insertion ring images — which remained our most detailed views of the rings for the past 13 years — I am taken aback by how vastly improved are the details in this new collection,” said Carolyn Porco, Cassini Imaging Team Lead at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “How fitting it is that we should go out with the best views of Saturn’s rings we’ve ever collected.”

The spacecraft will remain in the ring-grazing orbit until April 22, completing 20 laps around the planet before the mission’s final flyby of the large haze-enshrouded moon Titan nudges Cassini on a trajectory between Saturn’s cloud tops and its innermost ring for the spectacular “grand finale” phase of the multibillion-dollar, two-decade-long mission.

“These close views represent the opening of an entirely new window onto Saturn’s rings, and over the next few months we look forward to even more exciting data as we train our cameras on other parts of the rings closer to the planet,” said Matthew Tiscareno, a Cassini scientist who studies Saturn’s rings at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California.

Running low on fuel, Cassini will make 22 trips through the 1,500-mile (2,400-kilometer) ring gap just above Saturn from April 26 until Sept. 15, when the spacecraft will make a final destructive plunge into the planet, transmitting data on its atmosphere until the signal is lost.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.