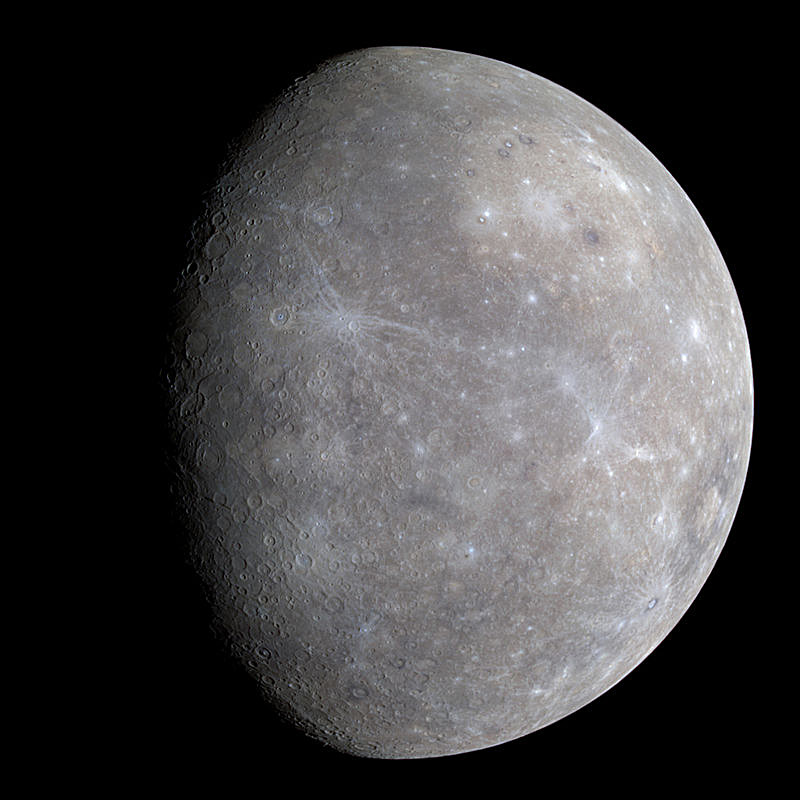

Have you ever seen Mercury with the naked eye? Not a lot of people have. The planet has a somewhat deserved reputation for being elusive and there are a number of reasons for this. It is, of course, the closest planet to the Sun, making one decidedly elliptical orbit of our nearest star every 88 days.

Mercury’s orbital eccentricity means that the farthest we can ever see the planet from the Sun varies between 18 and 28 degrees — scarcely more than the span of an outstretched hand held at arm’s length. Consequently, we can only see it with the naked eye either in the west at dusk or in the east at dawn, but rarely in a truly dark sky. (If one lived on the equator, then under very favourable circumstances it might be possible to see Mercury at eastern elongation setting in the west after the end of evening astronomical twilight, or at western elongation rising in the east just before the onset of astronomical twilight.)

On Monday, 18 April around 3pm BST, Mercury attains a greatest elongation of 19.9 degrees east of the Sun. This favourable aspect, combined with the current high inclination of the ecliptic to the UK’s western horizon at sunset, means that Mercury is higher in the sky and therefore lingers in the twilight glow longer than usual after the Sun sets — almost 2¼ hours after sunset, in fact, for the centre of the British Isles.

To increase your chances of seeing Mercury 13—24 April, you need to find a safe location that gives you a level and unobstructed view of the west-northwest horizon, preferably away from streetlights.

Low power, wide-field binoculars of the 7×50 or 7×35 variety will be excellent for sweeping the horizon for Mercury’s soft glow — but only do so after the Sun has set lest you cause irreparable damage your eyesight.

Help in locating Mercury close to elongation on or about 18 April comes in the form of first-magnitude star Aldebaran in Taurus. First locate the star due west, then look 22—23 degrees (the span of an outstretched hand at arm’s length, or three 7×50 binocular fields of view) to Aldebaran’s lower right to find the point of light that is Mercury.

If you consult our online Almanac, select the nearest town to your location and ensure that “Daylight Savings Time” is ticked. At the top right of the display, use the pull-down menu to select “Bright planets last/first visible” to display your local circumstances of the best time in the evening to make the attempt. Alternatively, just add one hour to the calculated local sunset time for any given April date.

Mercury resides in the constellation of Aries throughout the remainder of April. By the middle of the month, the planet’s magnitude is around -0.3, its apparent size is 7 arcseconds and its disc is half illuminated. As the days pass, Mercury’s angular size grows and its phase shrinks.

By the start of the third week of April the innermost planet’s disc has grown to 8.5 arcseconds, yet it is just a 29 percent illuminated crescent. However, discerning the phase of a planet so close to the horizon would entail considerable telescopic magnification and better seeing than afforded by its low altitude, but you should congratulate yourself on the success of merely locating this fascinating little world.

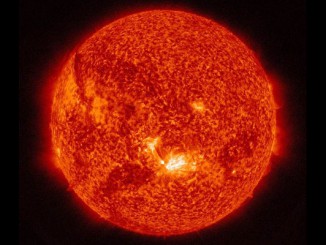

As April draws to a close, Mercury’s swift orbital motion about the Sun means that it grows closer to Earth and in angular size as more of its darkened hemisphere is turned toward us. The trade-off is that the planet is also swinging in between us and our nearest star, lining up for its almost 7½-hour-long transit of the Sun starting just after midday on Monday, 9 May. More on that spectacular event — and safe ways to view it — nearer the time.

Inside the magazine

Find out all you need to know about observing Mercury and the other solar system bodies currently in the night sky in the April 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.