“We’ve only seen surfaces like this on active worlds like Earth and Mars,” said mission co-investigator John Spencer of SwRI. “I’m really smiling.”

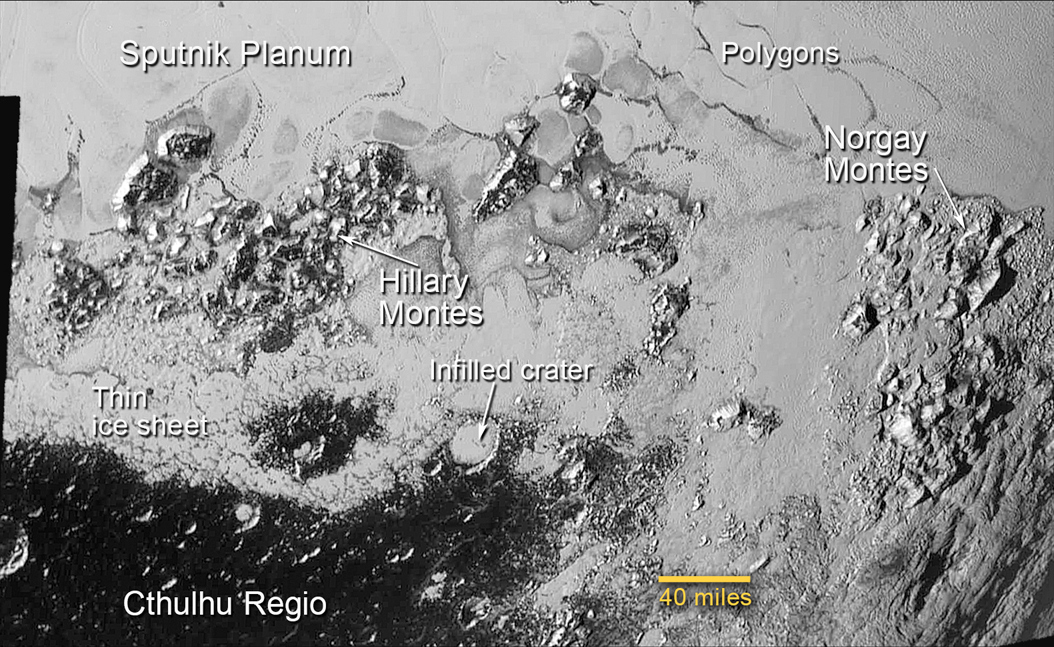

The new close-up images show fascinating detail within the Texas-sized plain (informally named Sputnik Planum) that lies within the western half of Pluto’s heart-shaped region, known as Tombaugh Regio. There, a sheet of ice clearly appears to have flowed — and may still be flowing — in a manner similar to glaciers on Earth.

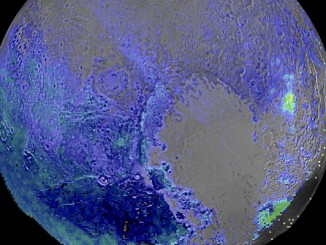

Additionally, new compositional data from New Horizons’ Ralph instrument indicate that the center of Sputnik Planum is rich in nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane ices. “At Pluto’s temperatures of minus-390 degrees Fahrenheit, these ices can flow like a glacier,” said Bill McKinnon, of Washington University in St. Louis, deputy leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team. In the southernmost region of the heart, adjacent to the dark equatorial region, it appears that ancient, heavily-cratered terrain (informally named “Cthulhu Regio”) has been invaded by much newer icy deposits.

“For many years, we referred to Pluto as the Everest of planetary exploration,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. “It’s fitting that the two climbers who first summited Earth’s highest mountain, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, now have their names on this new Everest.”

View a simulated flyover using New Horizons’ close-approach images of Sputnik Planum and Pluto’s newly-discovered mountain range — Hillary Montes — in the video below.