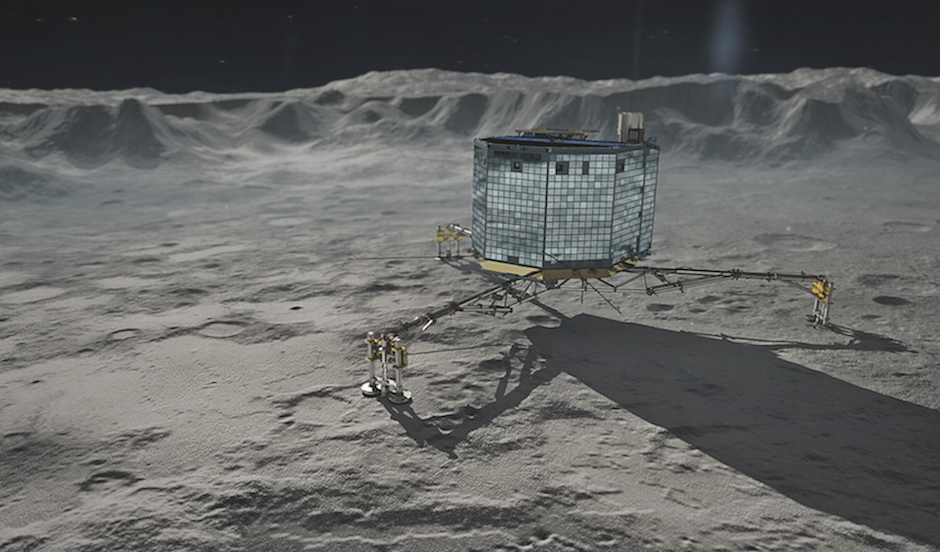

Emboldened by renewed contact with Europe’s comet lander, engineers are repositioning the mission’s Rosetta mothership this week to establish a reliable a communications link with the dishwasher-sized Philae landing craft, a prerequisite for resuming a science campaign abbreviated by a power shortfall last year.

The Rosetta spacecraft flying near comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko picked up radio signals from Philae twice Saturday and Sunday, officials said Monday.

Mission managers said both contacts were brief, but telemetry relayed to Earth through Rosetta indicated Philae was in fine shape after 211 days of silence lodged against a cliff somewhere on the comet’s craggy nucleus.

Temperatures on the lander have risen to minus 5 degrees Celsius (23 degrees Fahrenheit) – a favorable level – and the solar-powered probe reaches a peak power level of 24 watts when it receives maximum sunlight, according to the European Space Agency.

European space officials hailed Philae’s comeback in a press briefing Monday at the Paris Air Show.

“We know now that we can get in touch with Philae,” said Jean-Jacques Dordain, ESA’s director general. “It will be getting warmer and warmer on the surface of the comet because, until the 13th of August, the comet will get closer and closer to the sun, so we should have more and more opportunities to get in touch with Philae.”

Johann Dietrich-Woerner, chairman of the German space agency DLR, said ground controllers plan to ease into limited science operations with Philae as soon as a reliable link is established with the lander through Rosetta.

“We now have (nearly) three hours per day of sunshine on the Philae lander,” said Woerner, who will assume the top post at ESA from Dordain on July 1. “We will change the orbit of Rosetta in order to get a better connection, and we will start then with all the scientific work with the so-called non-mechanical instruments, meaning not the drilling.”

Philae shut itself down in November about 60 hours after coming to a stop on the comet’s nucleus. A cliff face blocked most sunlight at Philae’s final resting place, and the probe’s body-mounted solar panels received less than 90 minutes of illumination during each 12-hour rotation of the comet.

Data received from Philae show it now receives approximately 135 minutes each “comet day,” double the illumination the lander got in November.

“We are still examining the housekeeping information at the Lander Control Centre in the DLR German Aerospace Center’s establishment in Cologne, but we can already tell that all lander subsystems are working nominally, with no apparent degradation after more than half a year hiding out on the comet’s frozen surface,” said Stephan Ulamec, Philae’s project manager at DLR.

“While the information we have is very preliminary, it appears that the lander is in as good a condition as we could have hoped,” Ulamec said in a statement.

The first of Philae’s two radio contacts with Rosetta occurred late Saturday, when ground controllers received more than 300 telemetry packets – about 663 kilobits of data – that were stored aboard the lander’s computer for up to several weeks.

Saturday’s 85-second linkup was followed Sunday by a second connection lasting just a few seconds, according to ESA.

But Sunday’s contact gave engineers a glimpse into Philae’s current status.

“It is clear that we have had two contacts, and the last one was actually very short but it was real-time,” said Alvaro Gimenez, ESA’s director of science and robotic exploration. “The first one was only, so to speak, old data that was stored and transmitted. We see the system is improving. It’s getting the right temperature, and it’s going to work.”

Next up for Rosetta’s ground team based in Darmstadt, Germany, is a maneuver to alter the mothership’s path around the comet.

Rosetta has kept its distance from the nucleus since a close flyby 28 March put the spacecraft into safe mode after a cloud of comet dust confused the orbiter’s pointing system and caused its antenna to temporarily drift out of alignment with Earth.

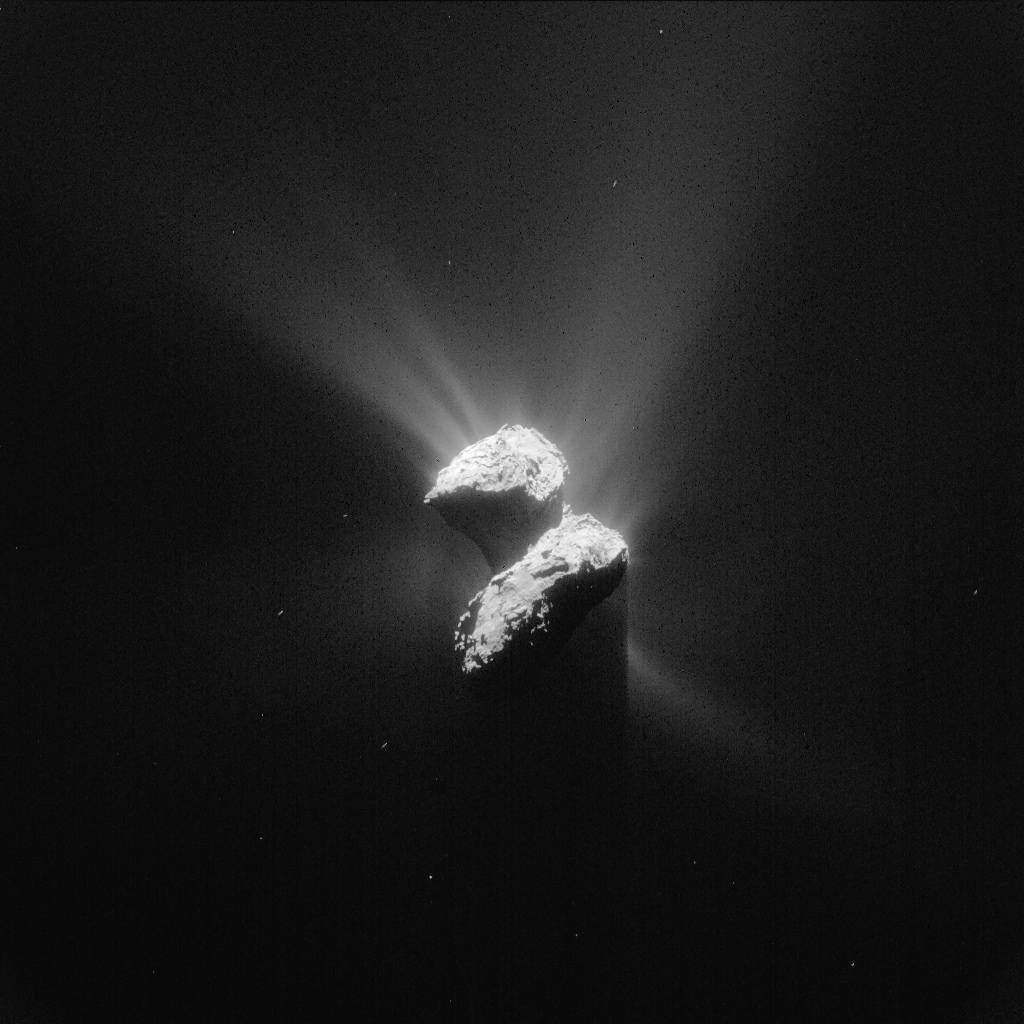

Barreling through space 304 million kilometres (188 million miles) from Earth, the comet is zooming toward the sun, and rising temperatures have activated jets of vapor and dust around the nucleus, complicating the task of navigating Rosetta.

“We are at a distance because it’s very dangerous to fly nearby,” Gimenez told reporters Monday.

Rosetta will change course at 2325 GMT on Tuesday to move from a distance of 235 kilometres (146 miles) to a range of 180 kilometres (112 miles), according to ESA.

“We had already planned a slight reduction of distance to the nucleus,” Andrea Accomazzo, ESA’s Rosetta flight director, wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now. “This, of course, plays in favor of contacts with the lander. On top of this, we will now redirect Rosetta to the portion of the sky where it was last Saturday when we had contact with Philae. If we had let Rosetta go on its planned trajectory, we would have several days without contact possibility.”

The control team planned to upload commands to Rosetta on Monday for Tuesday’s minor rocket burn to nudge the orbiter back toward the comet.

Rosetta should be in a good position to receive signals from Philae by Friday. Once Rosetta makes reliable contact with the lander, scientists can send commands for Philae to resume science operations, officials said.

“We are trying now to start working with the less power-consuming instruments, so we can make science with those instruments that don’t require mechanical power like drills or moving Philae or rotating Philae,” Gimenez said. “We will do that when we recharge the secondary battery.”

Science experiments could begin in less than a week, Gimenez said.

Rosetta continued its exploration of comet 67P after Philae entered hibernation, executing a series of close-up flybys earlier this year. Rosetta is expected to stay near the comet until some time next year, when it will likely be guided on its own descent to the nucleus.

“Most of the scientific data are coming from Rosetta itself, meaning that on a continuous basis we get scientific data with Rosetta,” Dordain said. “But it’s very good to have contact with Philae because we should also be able to receive information from the surface of the comet.”

Echoing earlier comments from Philae’s science team, Gimenez said the lander’s tumultuous touchdown – in which its anchoring harpoons, braking rocket and ice screws all failed – allowed the probe to settle in a location with enough shade to stay cool as the comet speeds toward its closest encounter with the sun in August.

Philae – the first probe to ever attempt landing on a comet – aimed for touchdown on a relatively flat sunlit region of comet 67P, a site selected by ESA for safety and to ensure the lander could recharge its batteries.

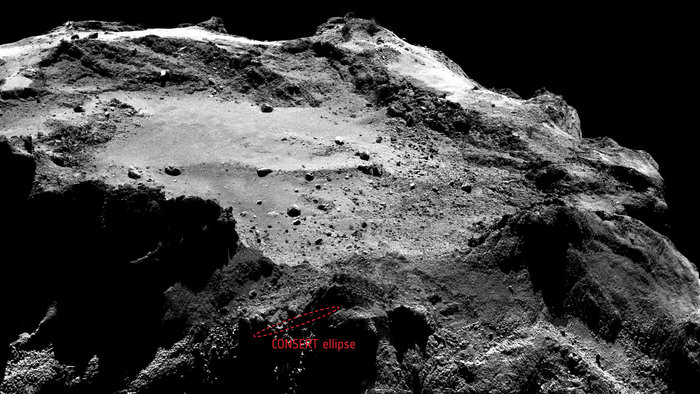

But the craft bounced off and ended up on a different part of the comet, and the same sun-blocking cliff that prematurely halted Philae’s mission in November should keep the probe from overheating as it approaches the sun. Scientists are still trying to pinpoint Philae’s exact location with high-resolution images from Rosetta and analysis of radio waves from the lander.

If Philae’s descent went perfectly, scientists expected the lander to stop working in March due to high temperatures.

“It was very fortunate that we landed where we landed and not in the other place because we could hibernate and then not be overheated when we were close to the sun,” Gimenez said. “We’ll be able to measure, for the first time ever, on a comet close to the sun when we are at perihelion. Otherwise, in the original plan, that would have not been possible.”

Gimenez chalked up the unexpected landing outcome as “good luck.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.