Although the commonly-used term ‘ghost crater’ is not a scientific definition, it nicely conjures up the image of a crater – or more appropriately, a topographically circular looking feature – that has so little prominence on the terrain that its circular outline may only be seen relatively fleetingly when it is illuminated by a very low Sun at local lunar sunrise or sunset.

Many of these so-called ghost craters are actually impact craters that, following their formation, were subsequently encroached upon by local lava flows that completely flooded their floors and covered all but the highest points around their rims. These features are known as embayed craters, since many of them appear adjacent to highland regions and form what appear like coastal bays. Indeed, some observers have identified sizable arcuate features in the maria that recall terrestrial archipelagos. Circular outlines of low-relief may also have other means of having been produced. For example, some of the arcuate wrinkle ridges within the circular lunar marial basins are known to be features that have resulted from the compression of lava-flows following basin-filling by marial lavas.

No thorough survey of lunar embayed craters has ever been made, but most of these lava-flooded features doubtless lie on the near-side of the Moon where a good thirty percent of the surface area is occupied by marial lava flows. The Moon’s far side is, of course, largely devoid of marial plains; only two percent of the surface area of the hidden side of the Moon is covered by volcanic lavas and only a handful of sizable embayed craters can be identified.

Remarkably, even a small telescope will reveal extremely subtle lunar formations such as ghost craters, marial wrinkle ridges and domes that are just a few tens of metres in elevation when they are illuminated at the sunrise or sunset lunar terminator.

‘Craters’ that trick

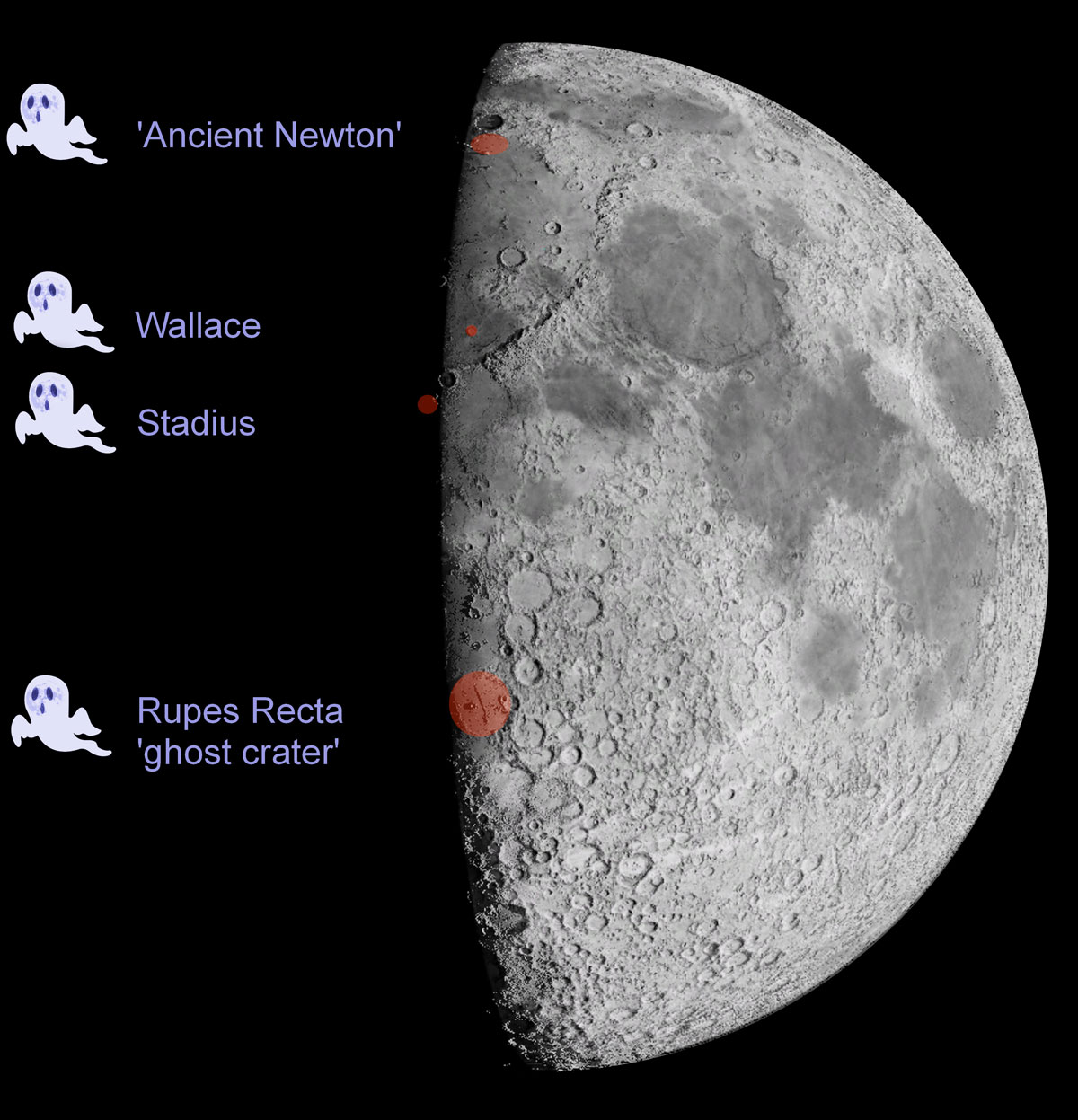

On the Halloween evening of 31 October, the sunrise terminator of the Moon’s waxing, slightly gibbous phase, brings to light three of the best-known lunar ghost craters. In the north the prominent dark-floored crater Plato (101 kilometres across) casts internal shadows that look like like spooky ‘Nosferatu fingers’ that stretch from the crater’s eastern rim across its floor, the actual motion of these eerie receding black forms being almost perceptible in real time. Looking immediately to the south of Plato, in northern Mare Imbrium, a 120-kilometre wide unnamed ghost crater, known unofficially as Ancient Newton, is clearly visible. The feature was first identified and named ‘Newton’ by the famous lunar observer Johannes Schröter (1745–1816). This is not to be confused with the officially recognised crater Newton, a 79-kilometre crater near the Moon’s crater-crowded southern limb which, along with its adjoining craters, appears very much foreshortened by the effect of perspective. The western ‘rim’ of Ancient Newton is made up of Montes Teneriffe, with Mons Pico in the south and an arcuate wrinkle ridge in the east; the northern embayment is also arcuate and cuts through the mountains in Plato’s southern glacis. In all, when observed illuminated by a low evening Sun as on this evening, ‘Ancient Newton’ is plainly visible.

Craters that treat

The crater Eratosthenes (58 kilometres) is very prominent near the terminator on Halloween evening. A nicely-formed little ghost crater called Wallace (26 kilometres across) can be clearly seen in Mare Imbrium around 100 kilometres north of Eratosthenes. Just south-west of Eratosthenes the eastern flanks of the ghost crater Stadius are beginning to emerge into the early morning Sun. Measuring 69 kilometres across, Stadius is a flooded crater whose rim is composed of narrow arcs of low hills (a few tens of metres in height) and the feature has been overlain with chains of small craters, many of which are are secondary impact features from Copernicus, 100 kilometres to the west. Some observers in the past mis-observed these little craters and speculated that they followed Stadius’ rim, implying that their formation was linked to Stadius itself. It could be argued that Stadius does not deserve a crater name, but because it is most probably a real flooded crater, like Wallace, I rather think it is here to stay.

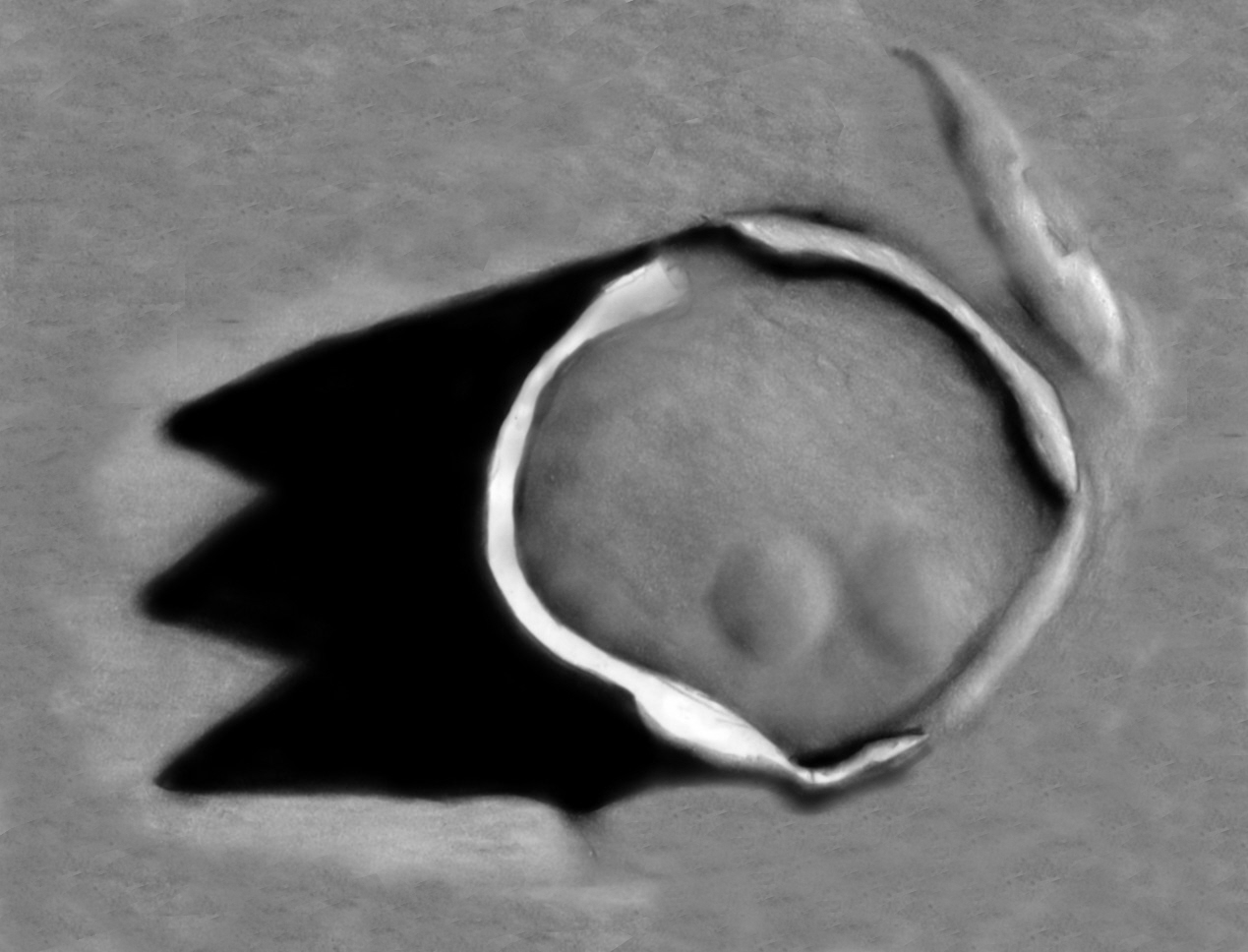

Finally, Halloween sees eastern Mare Nubium catching the rays of the rising Sun. Rupes Recta, the famous ‘Straight Wall’ – a 110 kilometre long cliff caused by crustal faulting – is very prominent as it casts its linear shadow westward. Closer scrutiny will reveal that Rupes Recta appears to run from north to south, bisecting what looks like an old embayed crater some 200 kilometres in diameter. The unnamed ghost crater’s eastern wall is well-defined as a bay in the mountains bordering Mare Nubium and tonight arcuate wrinkle ridges marking the buried crater’s western rim are clearly visible.

This article originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of Astronomy Now. Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s longest running astronomy magazine.