The lead author of the paper is Ryuki Hyodo (Kobe University Department of Planetology, Graduate School of Science), and co-authors are Professor Sébastien Charnoz (Institute de Physique du Globe/Université Paris Diderot), Project Associate Professor Hidenori Genda (Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology), and Professor Keiji Ohtsuki (Kobe University Department of Planetology, Graduate School of Science).

Centaurs are minor planets that orbit between Jupiter and Neptune, their current or past orbits crossing those of the giant planets. It is estimated that there are around 44,000 centaurs with diameters larger than one kilometre.

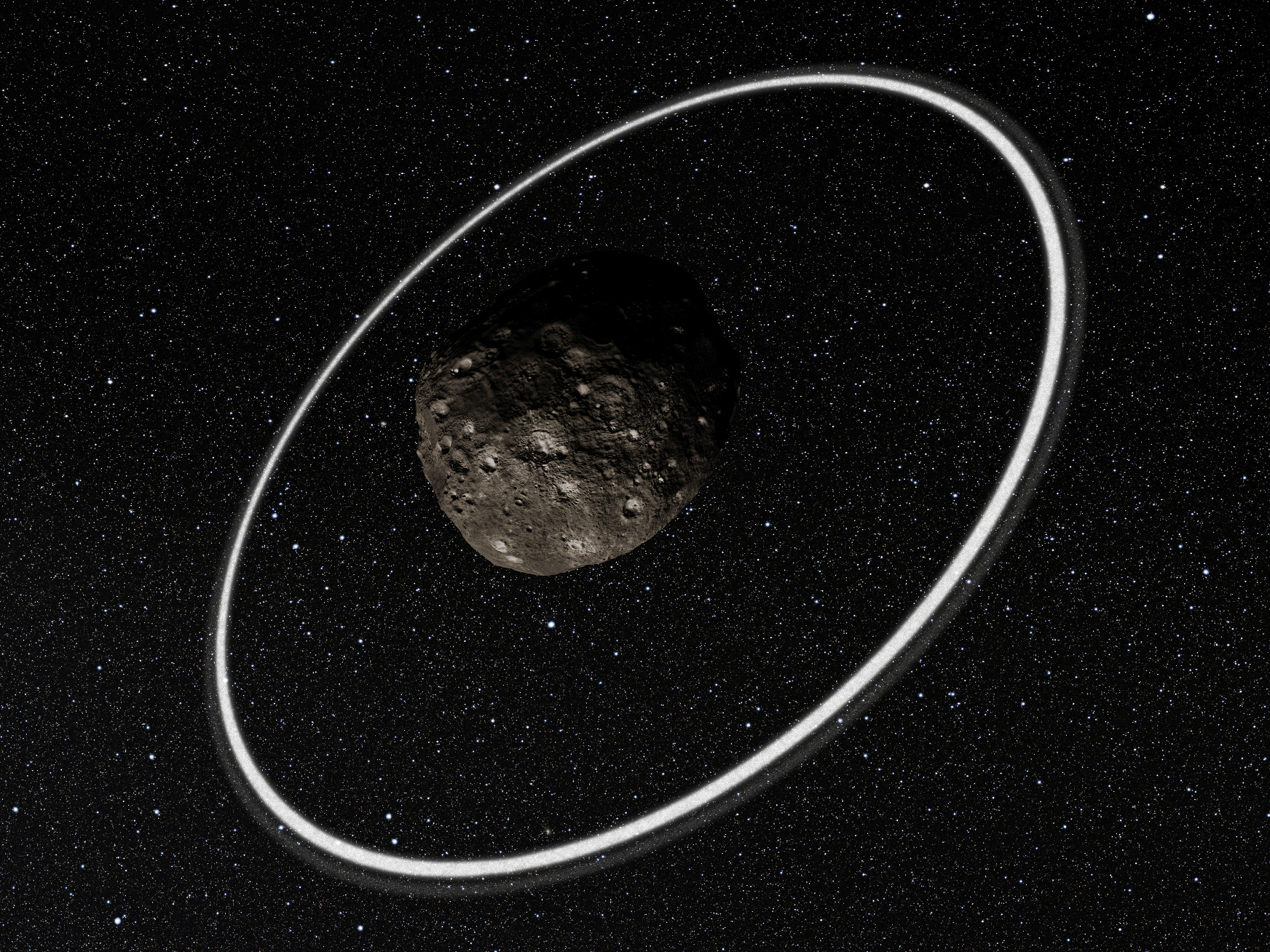

Until recently it was thought that the four giants such as Saturn and Jupiter were the only ringed celestial bodies within our solar system. However, in 2014 observations of stellar occultation (an event that occurs when light from a star is blocked from the observer by a celestial body) by multiple telescopes revealed that rings exist around the centaur 10199 Chariklo. Soon after this, scientists discovered that rings likely exist around another centaur, 2060 Chiron, but the origin of the rings around these minor planets remained a mystery.

The team began by estimating the probability that these centaurs passed close enough to the giant planets to be destroyed by their tidal pull. Their results showed that approximately 10 percent of centaurs would experience that level of close encounter. Next, they used computer simulations to investigate the disruption caused by tidal pull when the centaurs passed close by the giant planets. The outcome of such encounters was found to vary depending on parameters such as the initial spin of the passing centaur, the size of its core, and the distance of its closest approach to a giant planet. They found that if the passing centaur is differentiated and has a silicate core covered by an icy mantle, fragments of the partially-destroyed centaur will often spread out around the largest remnant body in a disc shape, from which rings are expected to form.

The results of their simulations suggest that the existence of rings around centaurs would be much more common than previously thought. It is highly likely that other centaurs with rings and/or small moons exist, awaiting discovery by future observations.