This discovery has given astronomers their first opportunity to measure the strength of these ultra-fast winds and prove they are powerful enough to inhibit the host galaxy’s ability to make new stars.

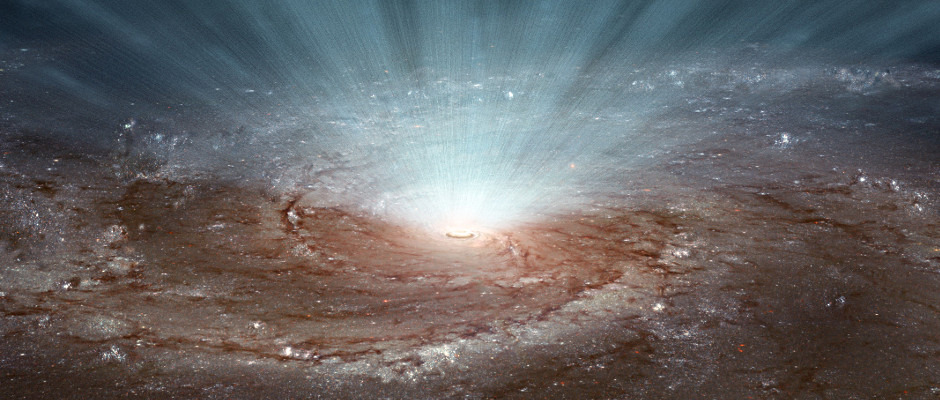

Supermassive black holes blast matter into their host galaxies, with X-ray-emitting winds travelling at up to one-third the speed of light. In the new study, astronomers determined PDS 456, an extremely bright black hole known as a quasar more than 2 billion light-years away, sustains winds that carry more energy every second than is emitted by more than a trillion suns.

“Now we know quasar winds significantly contribute to mass loss in a galaxy, driving out its supply of gas, which is fuel for star formation,” said the study’s lead author, Emanuele Nardini of Keele University in England.

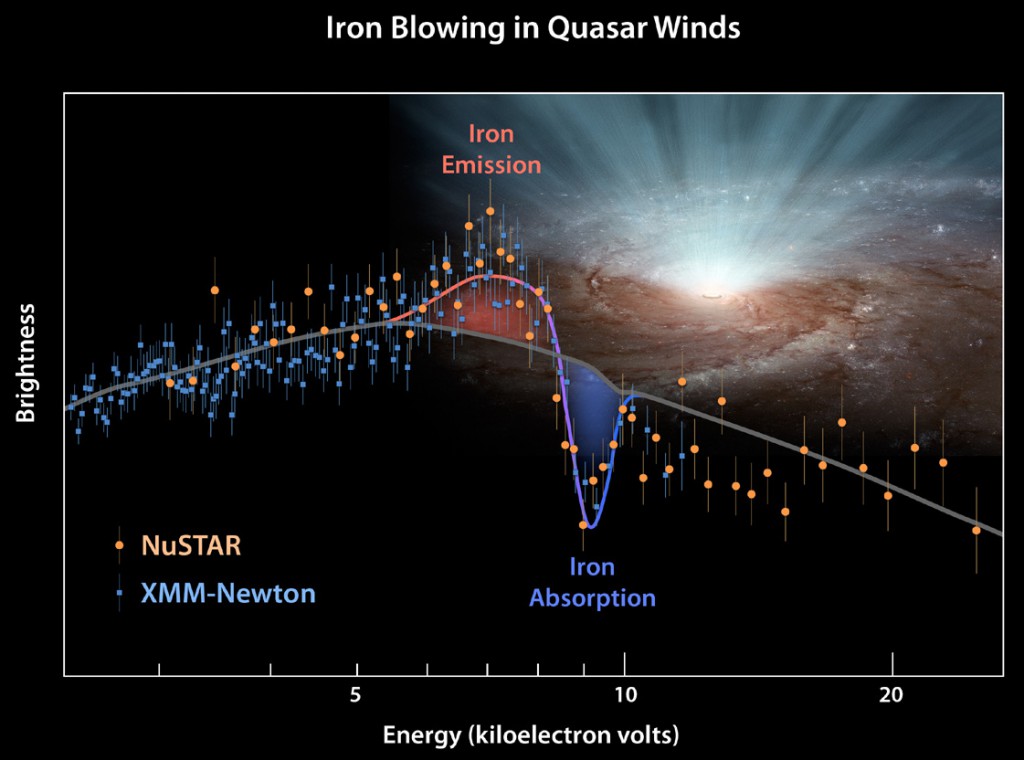

Previous XMM-Newton observations had identified black-hole winds blowing toward us, but could not determine whether the winds also blew in all directions. XMM-Newton had detected iron atoms, which are carried by the winds along with other matter, only directly in front of the black hole, where they block X-rays. The scientists combined higher-energy X-ray data from NuSTAR with observations from XMM-Newton. By doing this, they were able to find signatures of iron scattered from the sides, proving the winds emanate from the black hole not in a beam, but in a nearly spherical fashion.

With the shape and extent of the winds known, the researchers could then determine the strength of the winds and the degree to which they can inhibit the formation of new stars.

Astronomers think supermassive black holes and their home galaxies evolve together and regulate each other’s growth. Evidence for this comes in part from observations of the central bulges of galaxies — the more massive the central bulge, the larger the supermassive black hole.

This latest report demonstrates a supermassive black hole and its high-speed winds greatly affect the host galaxy. As the black hole bulks up in size, its winds push vast amounts of matter outward through the galaxy, which ultimately stops new stars from forming.

Because PDS 456 is relatively close, by cosmic standards, it is bright and can be studied in detail. This black hole gives astronomers a unique look into a distant era of our universe, around 10 billion years ago, when supermassive black holes and their raging winds were more common and possibly shaped galaxies as we see them today.

“For an astronomer, studying PDS 456 is like a paleontologist being given a living dinosaur to study,” said co-author Daniel Stern of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. “We are able to investigate the physics of these important systems with a level of detail not possible for those found at more typical distances, during the ‘Age of Quasars.'”