The date of Mars’ opposition and its least distance from Earth can differ by up to 8½ days. Earth is currently heading for aphelion (furthest from the Sun) on 4 July, while Mars has yet to reach perihelion (closest to the Sun) on 29 October in its orbit of greater eccentricity. A combination of opposition geometry, Earth’s growing distance from the Sun and Mars’ shrinking solar distance means that least distance between the two planets occurs at 21:29 UT (10:29pm BST) on Monday, 30 May when their centres will be 0.503223 astronomical units, or 46,777,480 miles (75,281,050 kilometres) apart.

How close can the Red Planet get to Earth?

The closest Mars has approached us in recent years was at 9:46 UT (10:46am BST) on Wednesday, 27 August 2003 at 0.372719 astronomical units, or 34,646,370 miles (55,757,920 kilometres). According to astronomical algorithm supremo Jean Meeus, the only time that Mars has gotten closer was in 57,617 BC! The next time Mars is super close is at 22:21 UT on 28 August 2287 (0.372254 astronomical units). However, we don’t have to wait too long to see another close Martian opposition: the Red Planet comes within 0.384966 astronomical units of Earth at 7:45 UT on 31 July 2018. (Data generated by NASA’s JPL HORIZONS system.)

For help in identifying the Martian surface features you may see in a telescope during the current opposition, don’t miss our interactive Mars Mapper web app.

Saturn at opposition

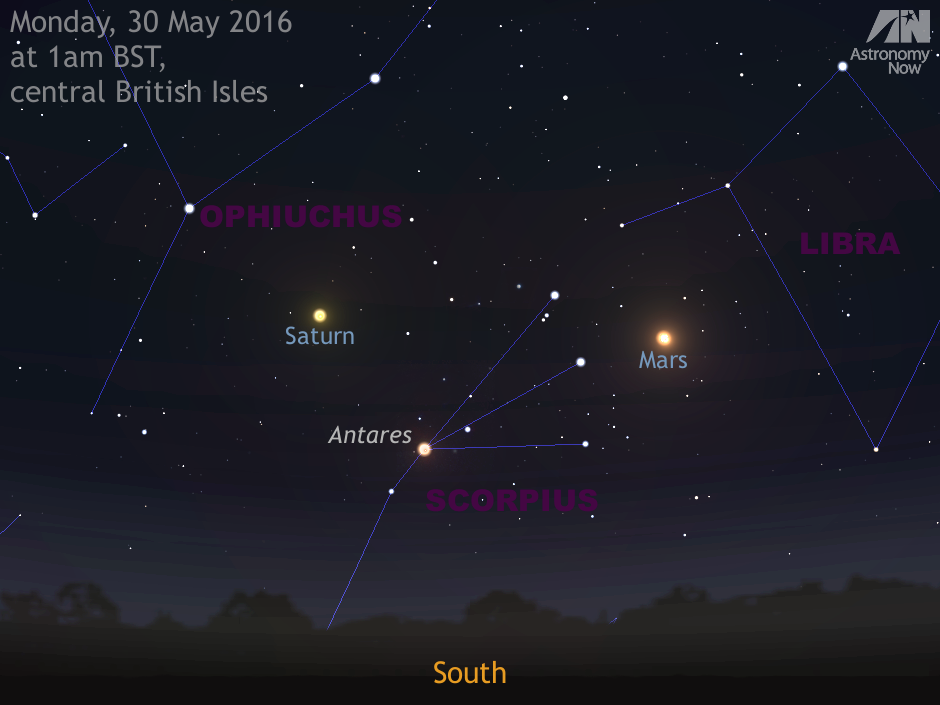

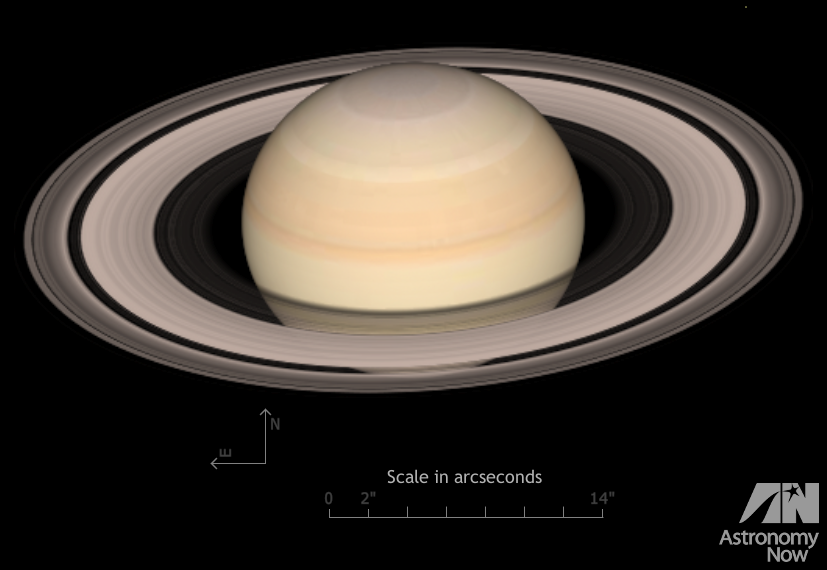

However, despite Saturn’s distance and low altitude as viewed from the UK, the planet’s oblate globe shines at magnitude zero and spans a respectable 18.4 arcseconds across the equator (almost identical to adjacent Mars, incidentally, at this time). This means that during June a telescope magnifying just 100x will enlarge Saturn’s disc to the same size as the Moon appears to the naked eye. Speaking of which, the 13-day-old waxing gibbous Moon lies just 2½ degrees above the planet late in the evening of Saturday, 18 June.

Saturn’s magnificent ring system is ideally presented this month. The plane of the rings (and the planet’s north pole) is tilted by 26 degrees to our line of sight, so their elliptical outline measures 18.4 by 41.8 arcseconds at best; if you look carefully in moments of good seeing this month you will see that the minor axis of the rings extends just beyond Saturn’s globe at the north and south poles. This is also an ideal time to see the so-called Cassini Division, the 3,000 mile-wide dark gap between the A and B rings. What’s the smallest telescope and magnification in which you can see this dark line in the ring system?

Saturn’s largest moon, 3,200-wile-wide Titan, orbits its parent planet every 16 days and is easy to spot in telescopes of 2-inch (5-cm) aperture or more as it shines at magnitude +8.5. Titan is at elongation, 4¼ ring diameters east of Saturn, on 10 June and 26 June. Titan may be found the same distance west of the planet on 2 June and 18 June.

If at all possible, do try to view Saturn and Mars within an hour or so of the time they transit (see our interactive Almanac for local times) so that they are as high as possible above your southern horizon. While there is not much we can do about poor seeing arising in the atmosphere, those nights that are slightly misty when a high pressure system sits above us often show the steadiest planetary views.

Inside the magazine

Find out all you need to know about observing Mars, Saturn and the other solar system bodies currently in the night sky in the June 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.