NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has revealed that some of the universe’s earliest galaxies were brighter than expected. The excess light is a byproduct of the galaxies releasing incredibly high amounts of ionising radiation. The finding offers clues to the cause of the Epoch of Reionization, a major cosmic event that transformed the universe from being mostly opaque to the brilliant starscape seen today.

No one knows for sure when the first stars in our universe burst to life. But evidence suggests that between about 100 million and 200 million years after the big bang, the universe was filled mostly with neutral hydrogen gas that had perhaps just begun to coalesce into stars, which then began to form the first galaxies. By about 1 billion years after the big bang, the universe had become a sparkling firmament. Something else had changed, too: Electrons of the omnipresent neutral hydrogen gas had been stripped away in a process known as ionisation. The Epoch of Reionization – the changeover from a universe full of neutral hydrogen to one filled with ionised hydrogen – is well documented.

Before this universe-wide transformation, long-wavelength forms of light, such as radio waves and visible light, traversed the universe more or less unencumbered. But shorter wavelengths of light – including ultraviolet light, X-rays and gamma rays – were stopped short by neutral hydrogen atoms. These collisions would strip the neutral hydrogen atoms of their electrons, ionising them.

But what could have possibly produced enough ionising radiation to affect all the hydrogen in the universe? Was it individual stars? Giant galaxies? If either were the culprit, those early cosmic colonisers would have been different than most modern stars and galaxies, which typically don’t release high amounts of ionising radiation. Then again, perhaps something else entirely caused the event, such as quasars – galaxies with incredibly bright centres powered by huge amounts of material orbiting supermassive black holes.

“It’s one of the biggest open questions in observational cosmology,” said Stephane De Barros, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. “We know it happened, but what caused it? These new findings could be a big clue.”

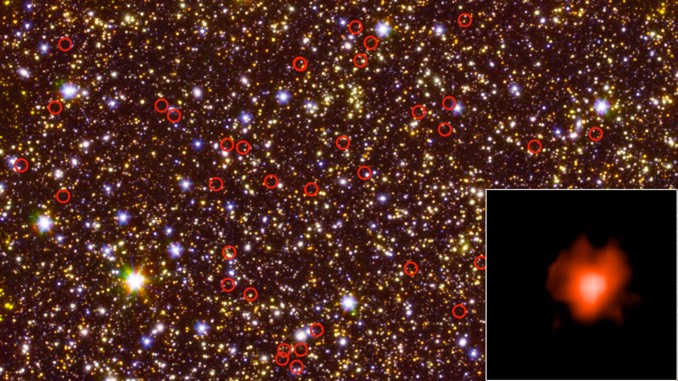

To peer back in time to the era just before the Epoch of Reionization ended, Spitzer stared at two regions of the sky for more than 200 hours each, allowing the space telescope to collect light that had traveled for more than 13 billion years to reach us.

The study, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, also used archival data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.

Using these ultra-deep observations by Spitzer, the team of astronomers observed 135 distant galaxies and found that they were all particularly bright in two specific wavelengths of infrared light produced by ionising radiation interacting with hydrogen and oxygen gases within the galaxies. This implies that these galaxies were dominated by young, massive stars composed mostly of hydrogen and helium. They contain very small amounts of “heavy” elements (like nitrogen, carbon and oxygen) compared to stars found in average modern galaxies.

These stars were not the first stars to form in the universe (those would have been composed of hydrogen and helium only) but were still members of a very early generation of stars. The Epoch of Reionization wasn’t an instantaneous event, so while the new results are not enough to close the book on this cosmic event, they do provide new details about how the universe evolved at this time and how the transition played out.

“We did not expect that Spitzer, with a mirror no larger than a Hula-Hoop, would be capable of seeing galaxies so close to the dawn of time,” said Michael Werner, Spitzer’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “But nature is full of surprises, and the unexpected brightness of these early galaxies, together with Spitzer’s superb performance, puts them within range of our small but powerful observatory.”