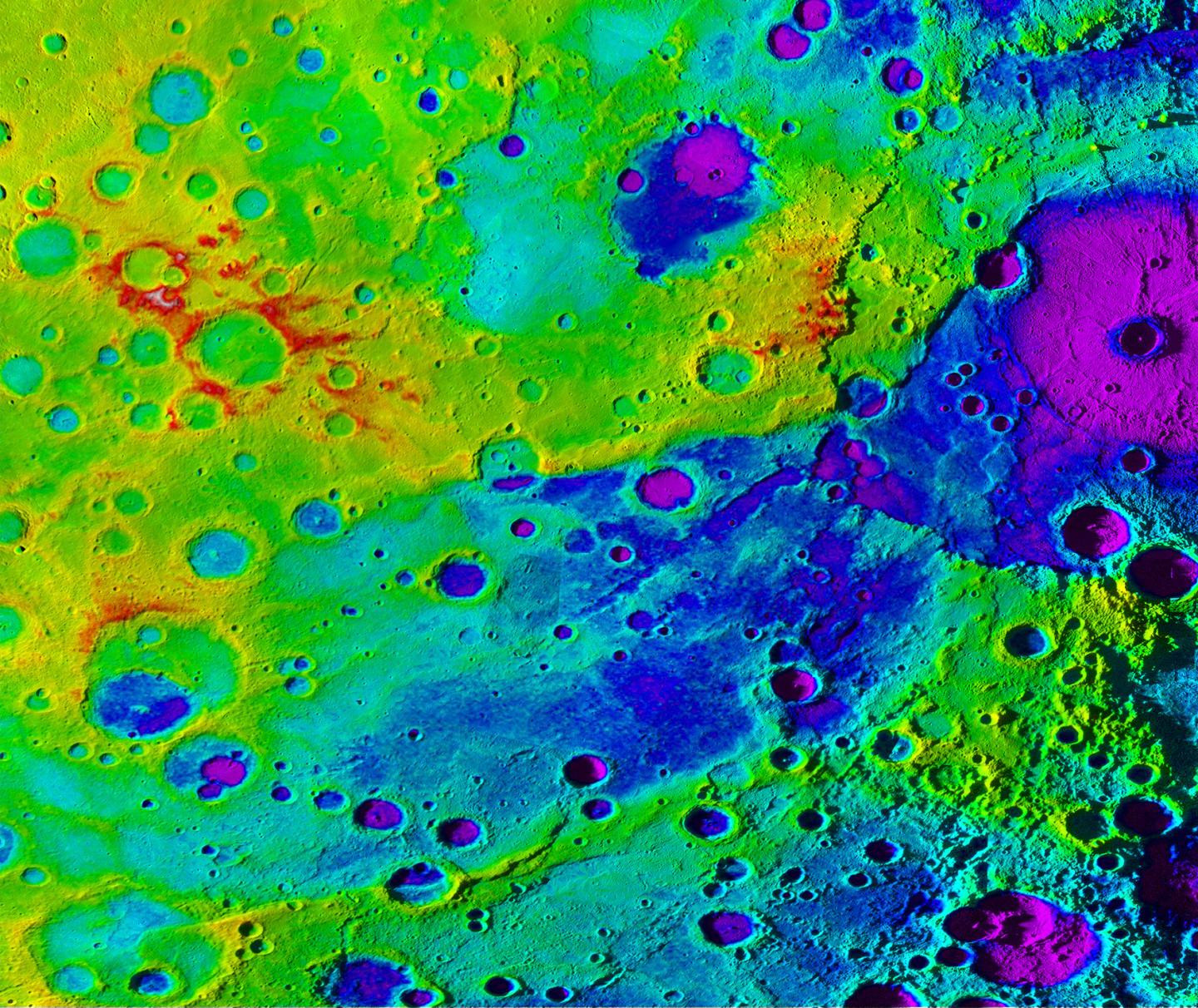

The most likely explanation for Mercury’s Great Valley is buckling of the planet’s lithosphere — its crust and upper mantle — in response to global contraction, according to the study’s authors. Earth’s lithosphere is broken up into many tectonic plates, but Mercury’s lithosphere consists of just one plate. Cooling of Mercury’s interior caused the planet’s single plate to contract and bend. Where contractional forces are greatest, crustal rocks are thrust upward while an emerging valley floor sags downward.

“There are examples of lithospheric buckling on Earth involving both oceanic and continental plates, but this may be the first evidence of lithospheric buckling on Mercury,” said Thomas R. Watters, senior scientist at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and lead author of the new study.

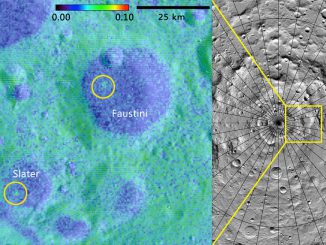

The valley is bound by two large fault scarps — steps on the planet’s surface where one side of a fault has moved vertically with respect to the other. Mercury’s contraction caused the fault scarps bounding the Great Valley to become so large they essentially became cliffs. The elevation of the valley floor is far below the terrain surrounding the mountainous faults scarps, which suggests the valley floor was lowered by the same mechanism that formed the scarps themselves, according to the study authors.

“Unlike Earth’s Great Rift Valley in East Africa, Mercury’s Great Valley is not caused by the pulling apart of lithospheric plates due to plate tectonics; it is the result of the global contraction of a shrinking one-plate planet,” Watters said. “Even though you might expect lithospheric buckling on a one-plate planet that is contracting, it is still a surprise when you find that it’s formed a great valley that includes the largest fault scarp and one of the largest impact basins on Mercury.”