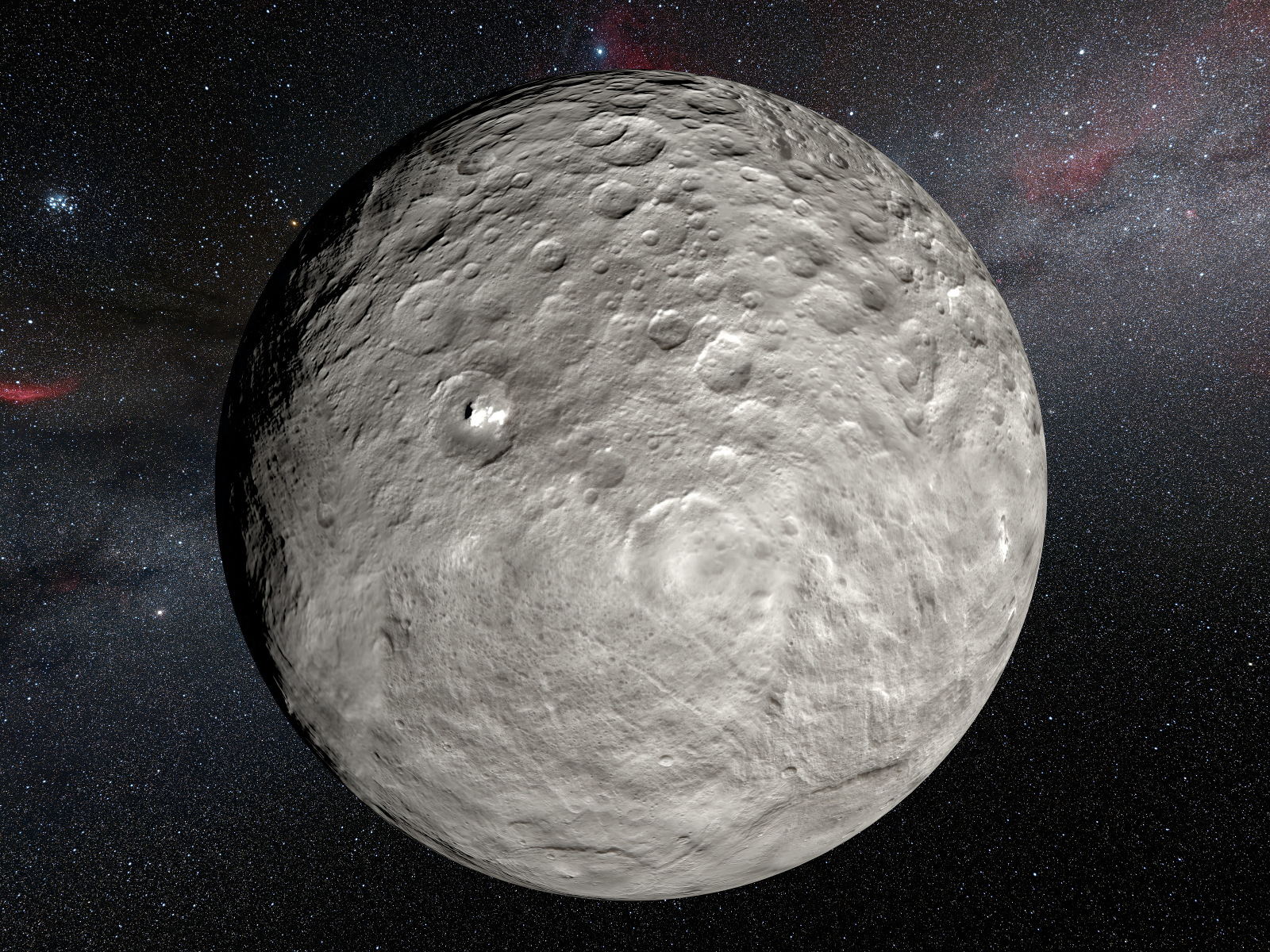

Ceres was at opposition on 21 October and currently shines at its peak magnitude of +7.4 for 2016, hence it’s a comfortable binocular or small telescope target on moonless nights — if you know exactly where to look. Viewed from the UK, the dwarf planet is currently highest in the sky close to 1am BST, some 35 degrees high in the south as seen from the centre of the British Isles.

When and how to see Ceres

Since last quarter Moon occurred on the evening of Saturday 22 October, the next few nights in the UK will be free of moonlight until after midnight, easing the task of finding Ceres. To identify it, one needs not only a moonless night when the dwarf planet is above the horizon murk, but a location that is largely free from light pollution.

So to ensure success, find a safe area as far removed from streetlights as you can and allow your eyes at least 15 minutes to become fully adapted to the dark. If you have printed both greyscale versions of the wide-angle and zoomed-in finder charts below, study them under a dim red light so as to preserve your night vision.

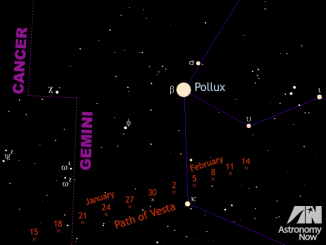

Start your search by identifying the Square of Pegasus — an asterism that is hard to overlook, found highest in the UK’s southern sky at 11pm BST in late October. Next, locate the square’s lower-left corner: magnitude +2.8 star gamma (γ) Pegasi, better known by its proper name of Algenib.

The next step entails moving 12 degrees (two-and-a-half 10×50 binocular fields) to the lower-left of Algenib until you reach magnitude +4.4 star delta (δ) Piscium — you are now on the curved east-west line of stars that forms the southern fish of the constellation Pisces.

With delta (δ) Piscium in your sights, you need to move a further 19 degrees (almost four binocular fields) to the lower left to reach your goal — a magnitude +3.8 star known as alpha (α) Piscium or by its proper name of Alrescha. To do this you will pass, in turn, epsilon (ε), zeta (ζ), mu (μ) and nu (ν) Piscium.

Having located Alrescha, you are now poised above the brown rectangle encompassing Ceres shown on the wide-field chart above, a region seen in far greater detail below. If you possess a 10×50 binocular — or any 7x or 8x instrument — and position Alrescha in the upper part of the field, you are certain to have Ceres in the same view as they are little more than 4 degrees apart. Note that the dwarf planet will be indistinguishable from a star, but its motion over a few nights will betray it.

Don’t miss planet Uranus!

While exploring this part of northern Cetus in search of Ceres, don’t overlook the fact that seventh planet Uranus, somewhat brighter at magnitude +5.7, lies just 13 degrees (or a span-and-a-half of a fist held at arm’s length) to the upper right of the dwarf planet, just over the constellation border into Pisces. Click here to see our observing guide to Uranus in October.

Inside the magazine

For a comprehensive guide to observing all that is happening in the current month’s sky, tailored to Western Europe, North America and Australasia, obtain a copy of the October 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.