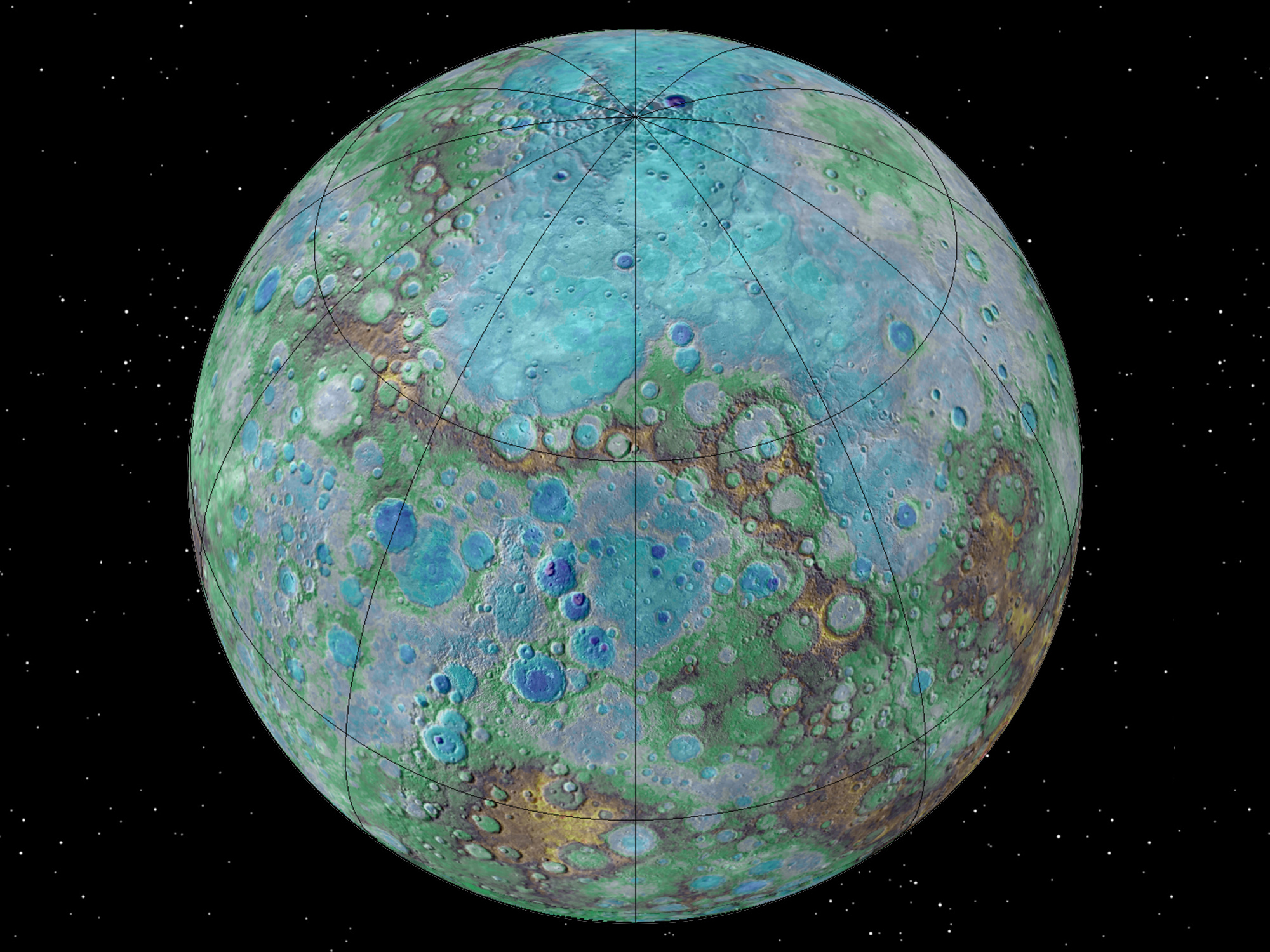

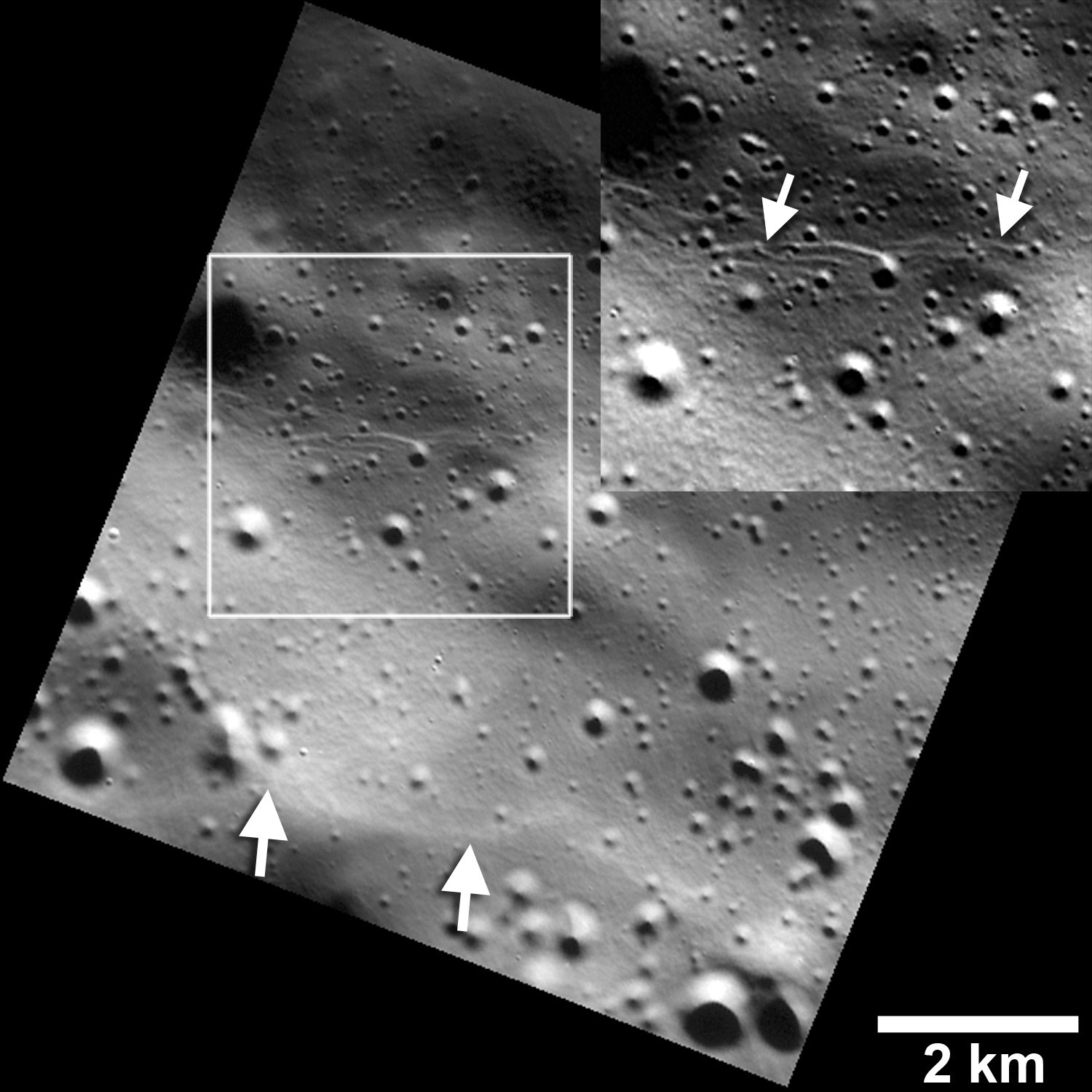

Images obtained by NASA’s MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft reveal previously undetected small fault scarps — cliff-like landforms that resemble stair steps. These scarps are small enough that scientists believe they must be geologically young, which means Mercury is still contracting and that Earth is not the only tectonically active planet in our solar system, as previously thought.

The findings are reported in a paper in the October issue of Nature Geoscience.

“The young age of the small scarps means that Mercury joins Earth as a tectonically active planet, with new faults likely forming today as Mercury’s interior continues to cool and the planet contracts,” said lead author Tom Watters, Smithsonian senior scientist at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Large fault scarps on Mercury were first discovered in the flybys of Mariner 10 in the mid-1970s and confirmed by MESSENGER, which found the planet closest to the Sun was shrinking. The large scarps were formed as Mercury’s interior cooled, causing the planet to contract and the crust to break and thrust upward along faults making cliffs up to hundreds of miles long and some more than a mile (over one-and-a-half kilometres) high.

This active faulting is consistent with the recent finding that Mercury’s global magnetic field has existed for billions of years and with the slow cooling of Mercury’s still hot outer core. It’s likely that the smallest of the terrestrial planets also experiences Mercury-quakes — something that may one day be confirmed by seismometers.

“This is why we explore,” said NASA Planetary Science Director Jim Green at Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “For years, scientists believed that Mercury’s tectonic activity was in the distant past. It’s exciting to consider that this small planet — not much larger than Earth’s Moon — is active even today.”

The innermost planet is currently very well placed for observation in the east at dawn. For further details, see our observing article.