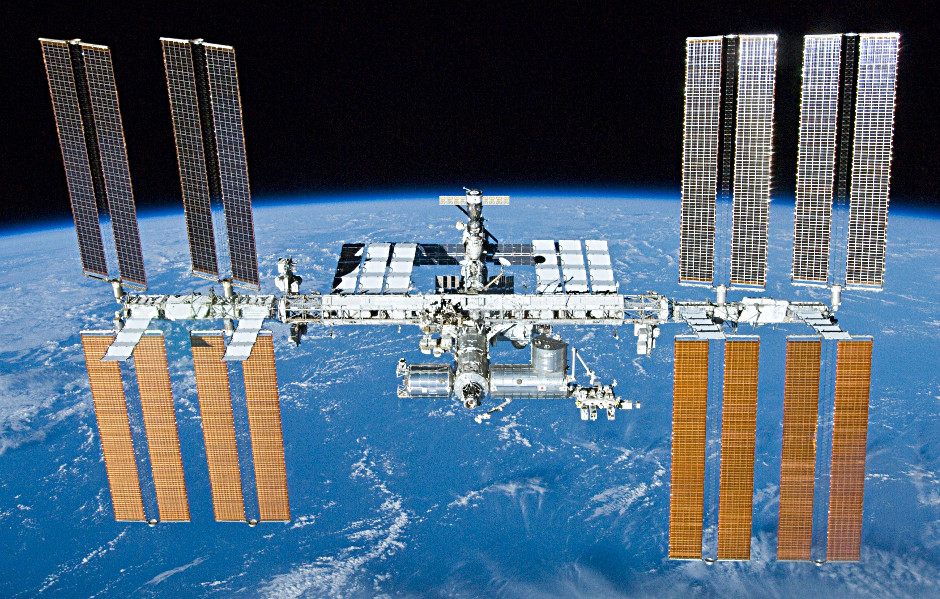

About the ISS

Construction of the ISS began with the launch of the first module, Zarya, in November 1998. Since then, more than 115 constructional space flights using five different types of launch vehicles have led to the 73 x 109 x 20 metre, 400-tonne structure that we see today. The orbital outpost has been continuously occupied since November 2000 and has seen 224 visitors from 18 countries.

Using Astronomy Now’s Almanac to make ISS viewing predictions

Many of you may have used our online Almanac to obtain information about lunar phases, or the rising and setting of the Sun, Moon and planets for wherever you may live, but the Almanac can also tell you when and where to see the International Space Station.

In the Almanac, select the closest city to your location from the Country and City pull-down menus before ensuring that the box beside Add ISS passes? has a tick in it and — just as importantly — the Daylight Savings Time? box, if applicable to your time and location. The table underneath the month’s Moon phase data then shows current nighttime passes of the International Space Station over your chosen location during the next five days, if any.

For the given Date in year/month/day format, Local Time is the instant the ISS first becomes visible and Duration indicates the length of the sighting in minutes. At the given Local Time, look in the direction indicated by Approach and, weather permitting, you should see the ISS as a slowly moving, bright ‘star’. Max. elevation is how high the Station will get above your horizon (90° is overhead, while 20° is about the span of an outstretched hand at arm’s length) and Departure indicates where the ISS will be when it vanishes from sight. Sometimes an appearance or disappearance occurs well up in the sky when the Station emerges into sunlight or slips into the Earth’s shadow, respectively.

Here is a recent example computed for the centre of the UK: In the example above, as seen from the heart of the British Isles on the evening of Tuesday, 2 August, the ISS first appeared 16° (a span and a half of a fist at arm’s length) above the west-southwest (WSW) horizon at 10:09pm BST in a viewing window lasting five minutes. It attained a peak altitude of 50° above the south-southwest (SSW) horizon before sinking down to 15° above the eastern (E) horizon at 10:14pm BST. One orbit later, the ISS rose again at 11:46pm BST.

In the example above, as seen from the heart of the British Isles on the evening of Tuesday, 2 August, the ISS first appeared 16° (a span and a half of a fist at arm’s length) above the west-southwest (WSW) horizon at 10:09pm BST in a viewing window lasting five minutes. It attained a peak altitude of 50° above the south-southwest (SSW) horizon before sinking down to 15° above the eastern (E) horizon at 10:14pm BST. One orbit later, the ISS rose again at 11:46pm BST.

Note: the actual times of events in the future will change as the orbit of the ISS varies over time; Almanac predictions made on the day are more accurate.

Viewing the ISS through a telescope?

In practice, trying to track the ISS with an undriven telescope such as a Dobsonian feels rather like clay pigeon shooting, as one attempts to anticipate where it will be in the finder before catching a glimpse as it flashes through the field a high-power eyepiece in a fraction of a second. However, practice makes perfect, and if a carefully focused astrovideo camera is used in place of an eyepiece, some frames on playback can contain tantalising images.

Observers with computerised mounts that can be driven by external software designed to track satellites a have much greater chance of success. Astrophotographers Thierry Legault and Ralf Vandebergh have succeeded in capturing stunning pictures of the ISS showing fine structural detail that are an inspiration to imagers the world over.

However, the serene beauty of the International Space Station sailing silently overhead needs nothing more than the naked eye or a binocular to appreciate. Furthermore, if you do make a sighting, contemplate the six-person crew of Expedition 48 that are currently aboard.

Inside the magazine

For a comprehensive guide to what is currently happening in the sky, obtain a copy of the August 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.