These works of fiction make a point of the actual fact that Barnard’s Star is one of the Sun’s nearest neighbours. Just 5.96 light-years away, it’s the closest red dwarf star to our Solar System and the fourth closest stellar body — only the three stars of the Alpha Centauri system are nearer (Proxima Centauri, or α Centauri C, is the closest at 4.24 light-years). At around 7–12 billion years of age, Barnard’s Star might also be among the oldest stars in our Milky Way galaxy.

We now know that Barnard’s Star’s proper motion of 10.3 arcseconds per year is the largest of any known stellar body. It’s a main-sequence red dwarf with a cool surface temperature of around 3,150K (2,877 ºC), has roughly one-sixth of the Sun’s diameter, 14 percent of its mass and shines with just 0.04 percent of the Sun’s luminosity. At magnitude +9.5, Barnard’s Star is too faint to see with the naked eye, but it’s the nearest nighttime star visible in a small telescope or large binoculars from the latitude of the British Isles, which is a good reason to track it down.

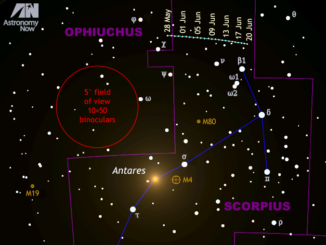

Since our target lies in the constellation of Ophiuchus, late Northern Hemisphere summer is a good time to look for it now that dark skies have returned to the British Isles. If you have access to a printer and haven’t already done so, click on the wide-field finder chart above (or this link) to obtain a scalable high-resolution PDF finder chart. With this in hand and the instructions that follow, you should be able to locate Barnard’s Star in small telescopes and large binoculars with little difficulty.

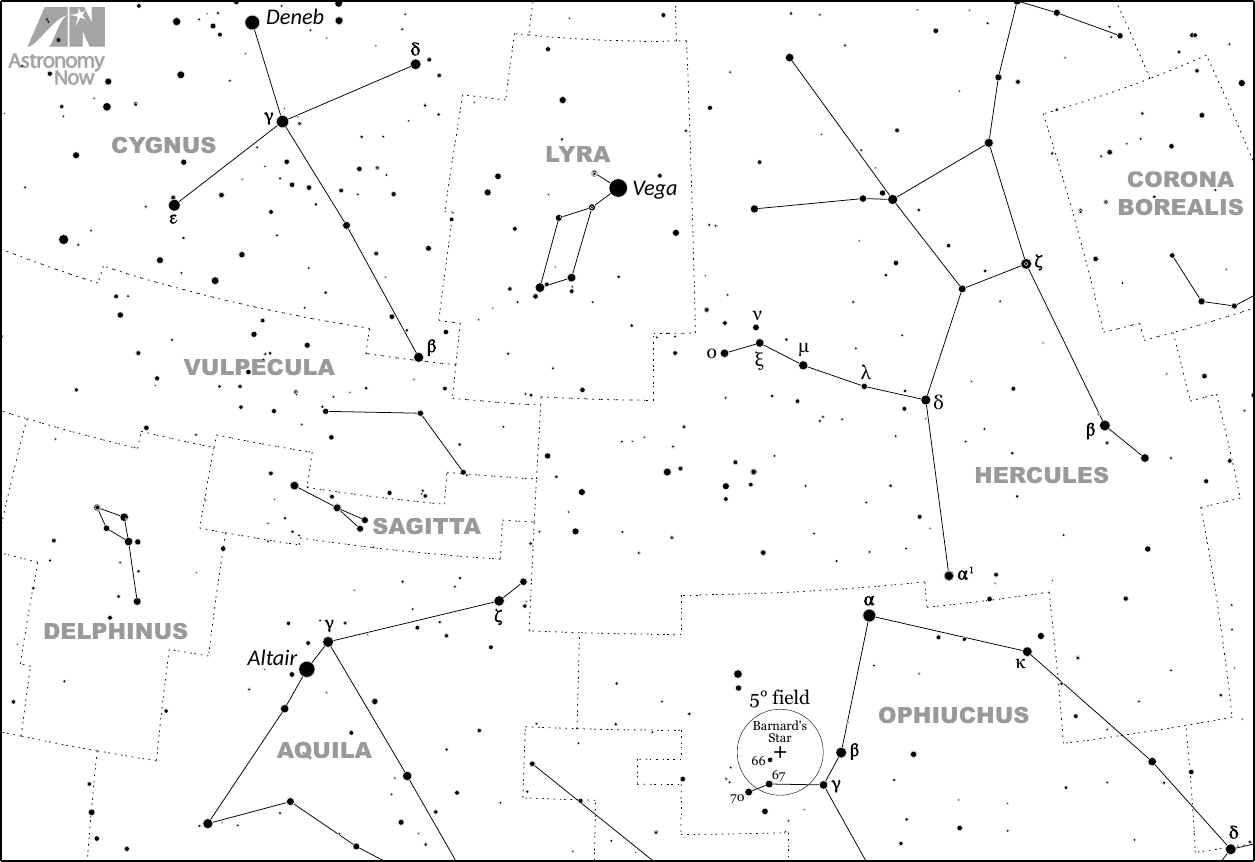

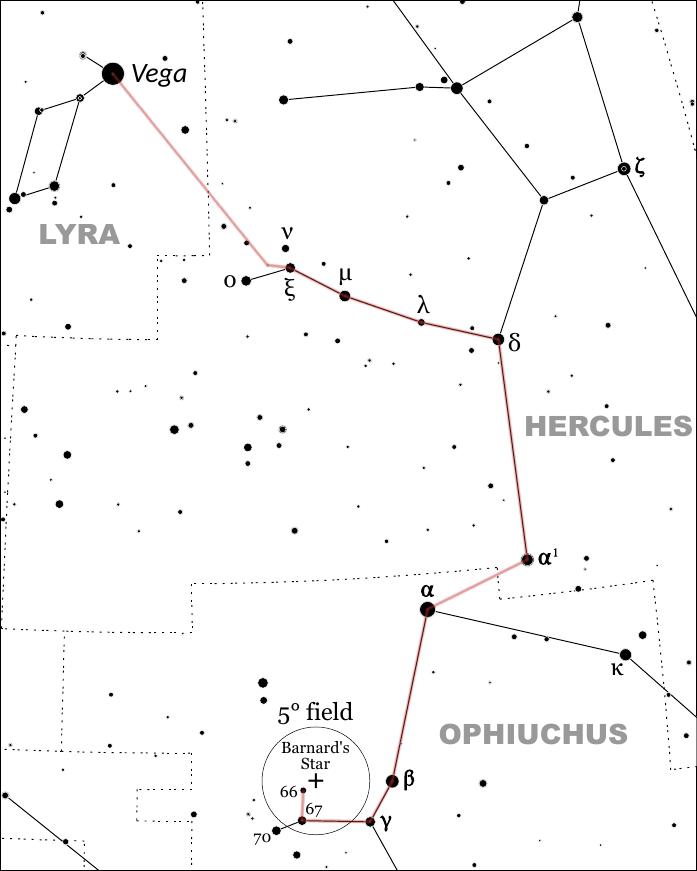

Starting our star-hop from Vega near overhead, move 12 degrees (half a span of an outstretched hand at arm’s length) to its lower right where you’ll find a triangle of third- and fourth-magnitude stars comprised of omicron (ο), nv (ν) and xi (ξ) Herculis – the trio is easily encompassed by 10×50 binoculars.

Your next waymark is second-magnitude α Ophiuchi (aka Rasalhague) some 5¼ degrees to the lower left of Rasalgethi. If you own a pair of 7× or 8× binoculars then you’ll be able to fit both Rasalhague and Rasalgethi in the same field of view.

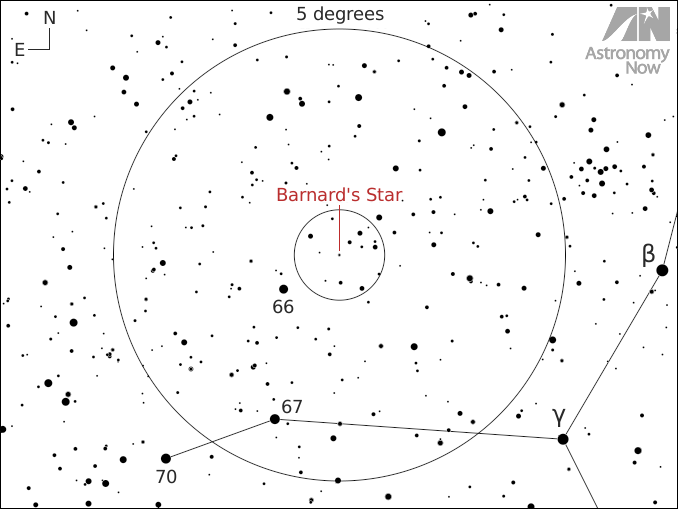

Now you’re on the home straight to Barnard’s Star. Two 10×50 binocular fields of view (or somewhat less than the span of a fist at arm’s length) to the lower left of Rasalhague brings you to magnitude +2.8 star β Ophiuchi. Next, follow a gentle curve through γ and 67, then turn through a right-angle north to 66 Ophiuchi. This last magnitude +4.8 star lies just 0.7° to the southeast of our target, so small telescopes at 40× magnification or less will show both 66 Ophiuchi and Barnard’s Star in the same field of view.

Now that you’re in the correct field, the problem lies in identifying which of all these faint background dots is Barnard’s Star, particularly in a large backyard telescope. That’s where the following detailed finder chart for users of large binoculars and telescopes comes in. (Click the graphic, or here, for a high-resolution PDF version suitable for printing and use outside.)

If you have a telescope with a computerised GoTo mount then there’s a far quicker way to find it. Just enter the following J2000 coordinates into your hand controller: α = 17h 57.8m, δ = +04° 45’. If your telescope requires GoTo coordinates for the current (J2018.6) epoch, use: α = 17h 58.7m, δ = +04° 45’.

The future of Barnard’s Star

Since a large component of its motion through space – 108 kilometres (67 miles) per second – is directed towards the Sun, the distance between our Solar System and Barnard’s Star is steadily decreasing to a minimum distance of 3.85 light-years by the year 11,800.

Could Barnard’s Star possess planets? A careful analysis of an apparent wobble in the star’s path by Peter van de Kamp and his colleagues at Sproul Observatory in Pennsylvania led to an announcement in 1963 that the star was attended by a planet about 1.6 times the mass of Jupiter orbiting every 24 years. Sadly, however, the data was in error due to adjustments made to the measuring telescope. Then, in November 2018, researchers announced the discovery of a rocky super-Earth designated Barnard’s Star b with a mass of at least 2.3 times that of Earth orbiting the star every 233 days.

Given Barnard’s Star’s great age, you may be surprised to learn that it exhibits occasional flare activity due to the release of magnetic field energy. The star likely has starspots, from which a rotational period of 130 days is suggested. Due to its variability, the star also has the designation V2500 Ophiuchi.