Views from Europe’s Rosetta comet orbiter show mysterious markings appearing on the nucleus of Comet 67P in recent months, with new surface features forming within a matter of weeks, and scientists are digging into the complex causes of the cometary erosion.

Heating from the sun likely plays a large role in driving changes on the comet’s nucleus, but the story is more complex, scientists said Friday.

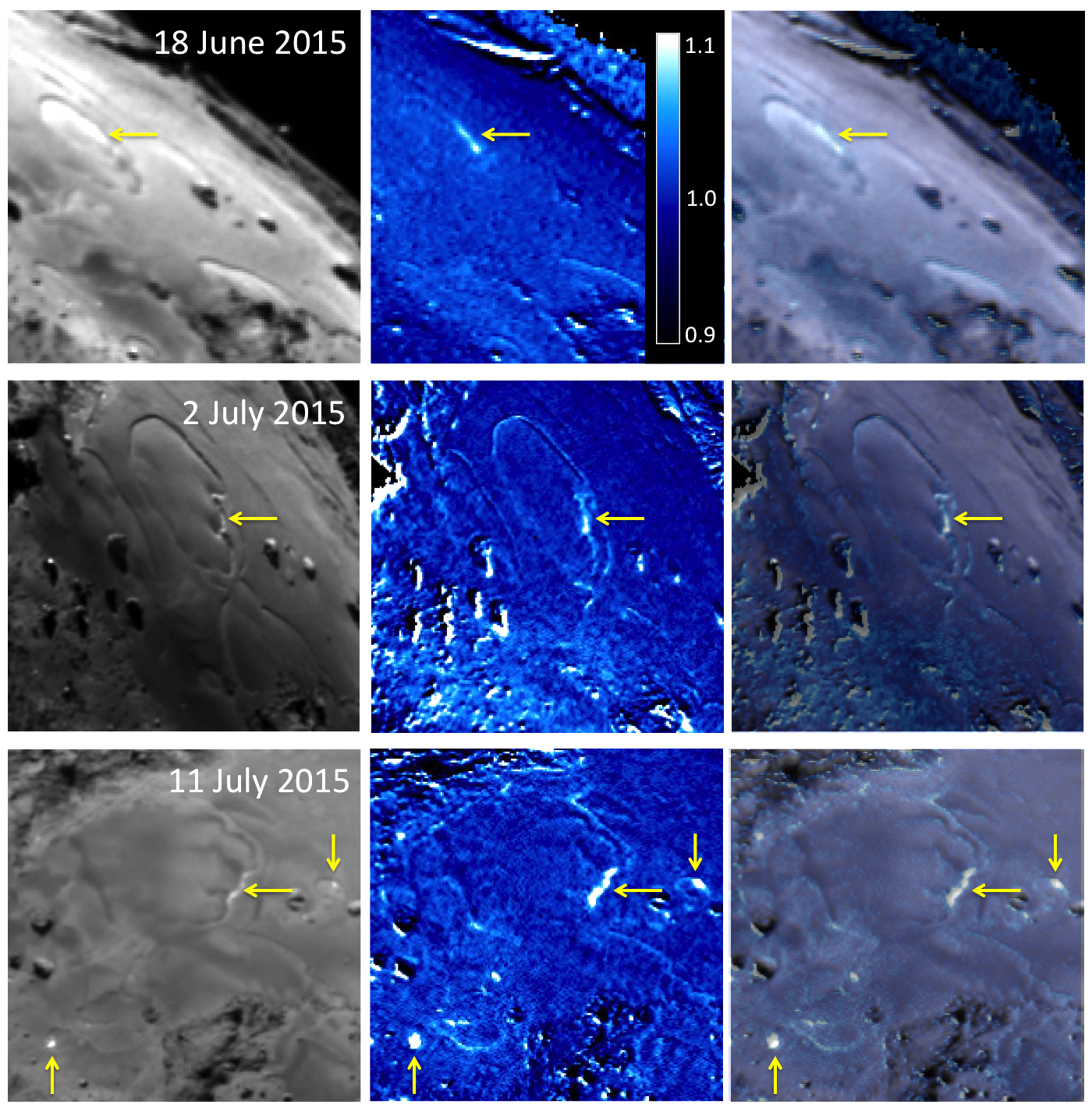

A sequence of images taken by Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera from May through July reveals fresh round features on the larger lobe of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, in a region dubbed Imhotep marked with large boulders and smooth plains that may be covered in granular deposits.

The Imhotep region, near the comet’s equator, sees prolonged sunlight during each 12.4-hour rotation.

The changes are more subtle than the brilliant outbursts periodically captured by Rosetta’s camera as Comet 67P passed perihelion, the point in its orbit closest to the sun.

“We had been closely monitoring the Imhotep region since August 2014, and as late as May 2015, we had detected no changes down to scales of a tenth of a meter (4 inches),” said Olivier Groussin, an astronomer at the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, France, in a blog post on the European Space Agency’s website.

“Then one morning we noticed that something new had happened: the surface of Imhotep had started to change dramatically,” said Groussin, a co-investigator on Rosetta’s OSIRIS instrument and lead author of a paper on the discovery to be published in Astronomy and Astrophysics. “The changes kept going on for quite a while.”

The first evidence for a new feature in the Imhotep region came in an image captured June 3. By June 13, a second marking appeared nearby, and the two features reached diameters of 220 meters (721 feet) and 140 meters (459 feet) in an image recorded by Rosetta on July 2, according to ESA.

That is significant growth on a comet that measures 4.1 kilometers (2.5 miles) across on its longest axis.

A third feature also appeared July 2, and the three disturbances had merged by July 11, with another two new markings showing up.

ESA said the perimeters of the features progressed across the comet’s surface at a few tens of centimeters per hour, or about one foot per hour — equivalent to more than 20 feet every day.

“This highlights the complexity of the physical processes involved,” Groussin said.

According to the paper published in Astronomy and Astrophysics, scientists think the markings eroded a depth of up to 5 meters (16 feet) relative to surrounding terrain.

Volatile molecules just underneath the comet’s outer veneer of dust and rock heat up as it nears the sun. Comet 67P reached perihelion between the orbits of Earth and Mars on Aug. 13.

As temperatures rise on the airless nucleus, volatiles such as water ice can sublimate — turning directly from a solid to a gaseous state — and blow away from the comet.

Color images from Rosetta may show exposed ice near the rims of the expanding features eating into surrounding material in the Imhotep region, but the markings grow much faster than scientists would expect if the changes were driven only solar heating.

The surface material may be very weak, allowing the features to spread faster, or more exotic chemical processes could be aid their growth.

“We are looking forward to combining our OSIRIS observations with data from other instruments on Rosetta, to piece together the origin of these curious features,” Groussin said.

OSIRIS did not see any sign of dust being lofted from the nucleus as the surface markings manifested, but scientists have not ruled out that material eroded by the growing features made its way into space or fell back to the comet.

Scientists predicted the comet would shed material during perihelion, but the discovery of ongoing erosion in the Imhotep region was the first time Rosetta found clear-cut evidence of surface changes since the spacecraft arrived at Comet 67P in August 2014.

Rosetta has found evidence of erosion from previous perihelion passages elsewhere on the comet, scientists wrote in the paper describing the discovery.

“The dramatic changes observed on Imhotep are a spectacular event, unique to comets, with a currently unpredictable end state,” scientists wrote in Astronomy and Astrophysics. “We will continue to carefully monitor this region during the coming months to better constrain the erosion processes responsible for these changes. Registering changes on 67P remains a key scientific objective for all Rosetta instruments to better understand how comets work and evolve.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.