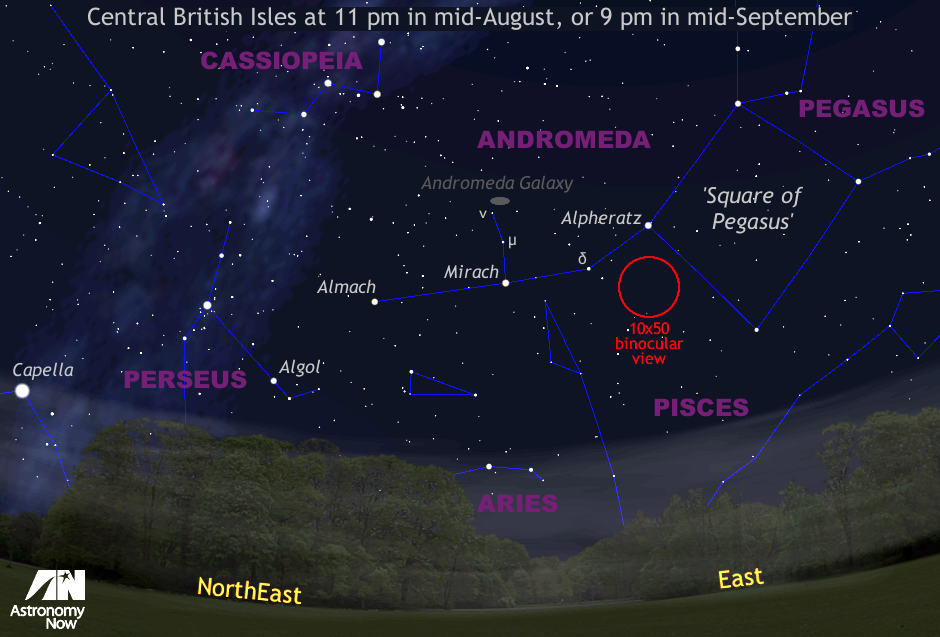

During the annual Perseid meteor shower vigil, my thoughts and gaze often turn to one of best deep-sky objects of the approaching season that is now accessible low in the east-northeast by 11pm BST — the Andromeda Galaxy, or Messier 31. By the middle of September, it can be observed at the same position by 9pm.

Some 2.5 million light-years away, M31 is often quoted as being the most distant object that we can see with the unaided eye on moonless nights from locations free of light pollution. Around 220,000 light-years in diameter, M31 is a spiral galaxy about 1.5 times larger than our Milky Way, making it the largest member of the Local Group. It could contain a trillion (1012) stars.

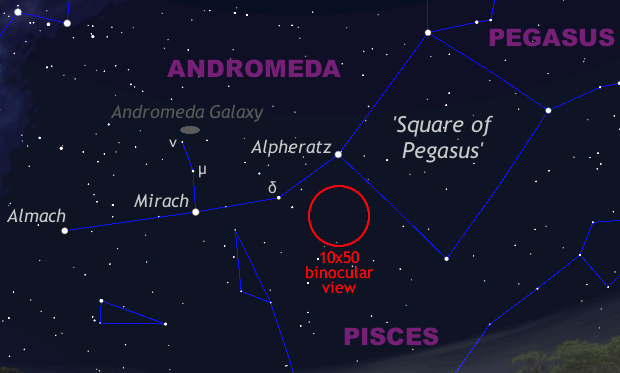

At its stated distance the Andromeda Galaxy has an angular size of about 5 degrees — the same as the apparent field of view of a typical 10×50 binocular. For this reason, when it comes to making observations of M31, very low magnification instruments under very dark skies will often deliver the most memorable views.

Star-hopping to the Andromeda Galaxy

If you wish to see M31 over the next few nights about 11 pm then you will need a clear eastern horizon away from the glare of streetlights. A rural site is always best, particularly where no towns lie to the east. The Moon is currently a very young waxing crescent and will not become obtrusive in UK skies until around Thursday, 20 August. A pair of 7×50, 8×40 or 10×50 binoculars will be a great help, if you own or can borrow a pair.

Next, divert your gaze to the east, where the so-called ‘Square of Pegasus‘ (though ‘Diamond of Pegasus’ may be more appropriate for its orientation at this time) lies a third of the way from the horizon to overhead. The diagonals of the square are about the span of an outstretched hand at arm’s length.

The left-hand star of the square — magnitude +2 star Alpheratz — is the starting point of our star hop to M31. In a 10×50 binocular, you need to move three fields of view to the left, passing magnitude +3.2 star delta (δ) Andromedae, until you reach magnitude +2 star Mirach.

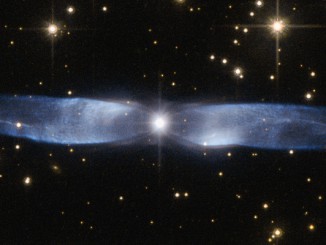

The Andromeda Galaxy is in the same binocular field as nu Andromedae (this blue star is also shown in the astrophotograph at the top of the page). Observers with aligned computerised GoTo mounts can take the fast-track route to M31 by selecting it from the Messier object menu, or by using these J2000.0 coordinates: α = 00h 42.7m, δ = +41° 16′

While in the area, telescope users may care to look at the beautiful contrasting colours of double star Almach, otherwise known as gamma (γ) Andromedae: α = 02h 03.9m, δ = +42° 20′ (J2000.0).

Once you have the satisfaction of locating the Andromeda Galaxy — and try to grasp that the soft glow in your binocular results from the combined light of a trillion stars — it is sobering to contemplate that M31’s light we perceive now set out on the long journey to Earth at the dawn of humankind.

Reflect, too, on the discovery that the Andromeda Galaxy is approaching our Milky Way at about 68 miles (110 kilometres) per second and the two will collide and merge to form a giant elliptical galaxy, or perhaps even a large disc galaxy. Don’t lose any sleep over it though — it is not going to happen for a further four billion years! Clear skies.

Inside the magazine

You can find out more about observing this month’s deep-sky objects in the August edition of Astronomy Now in addition to a full guide to the night sky.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.