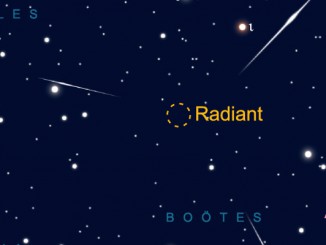

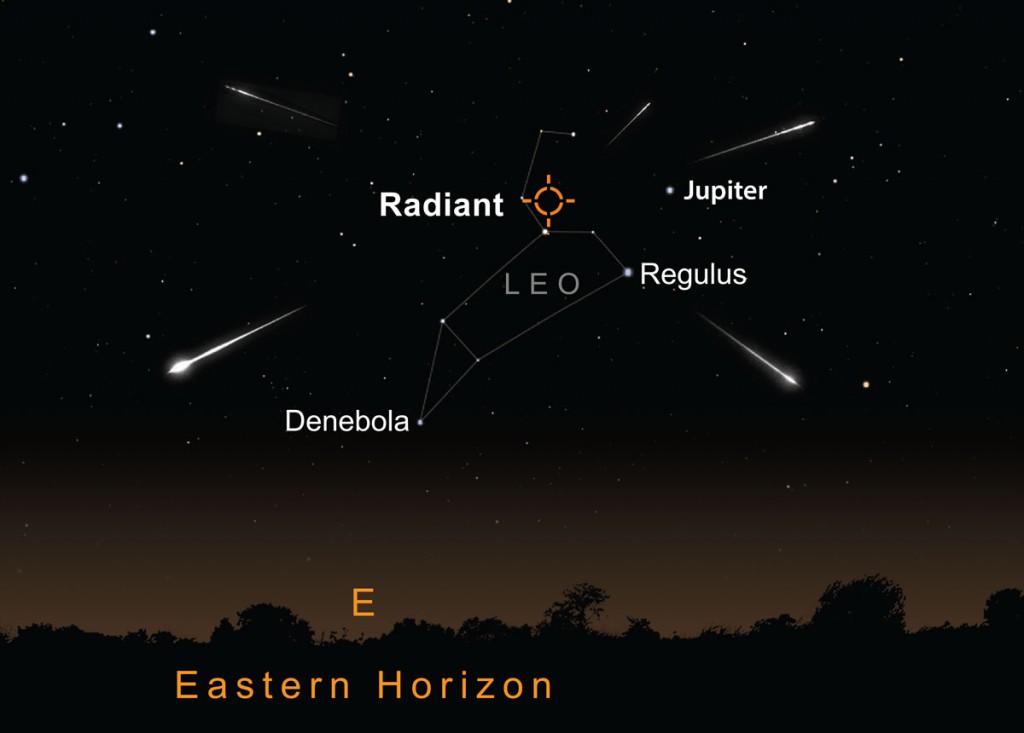

The Leonid meteor shower has been active for a few days now and builds towards its peak around 1am this coming night (17/18 November). We can expect around 20 meteors per hour at best, with the radiant rising in the UK after 9pm.

The radiant is the point among the stars where the meteors appear to fan out from; for the Leonids it’s close to the Sickle asterism, the backwards question-mark pattern of stars in Leo with first-magnitude Regulus marking the ‘full-stop’. This year the view will be graced by the imposing presence of brilliant Jupiter, lying just eight degrees west of Regulus.

By the time of the Leonid’s predicted peak the radiant will be around 30 degrees above the eastern horizon and so quite well-placed. The real good news is that the Moon will not blight this year’s show, its phase being a 22 percent illuminated crescent that rises after 2.30am and doesn’t creep above 20 degrees elevation until 5am. Leonid meteors often leave many persistent tracks or trains across the sky; Leonids are very fast meteors, with entry velocities of 70 kilometres per second.

This year’s Leonids show favours Europe but observers in North America can still look out for the shooting stars; from New York latitudes the radiant rises at 10pm, five hours after the predicted peak but meteor showers can throw up surprises, so it’s always worth conducting a watch.

As with observing any meteor shower the best advice is not to stare at the actual radiant but at an altitude of 50 degrees (about the same altitude of the Pole Star from the UK) and 30-40 degrees to one side of the shower radiant (the width of a fist held at arm’s length is about ten degrees). November nights can be bone-chilling so wrap up well in layers of warm, dry clothing and keep your hands, feet and head warm.

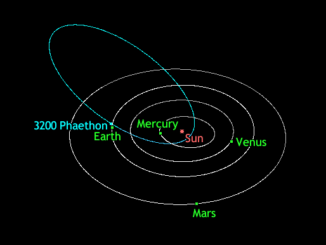

The Leonids are seen every year between November 15-20 as the Earth passes close to the descending node of the orbit of comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, the shower’s parent comet. In common with all comets, Tempel-Tuttle sheds a stream of small particles and meteoroids around the time it is closest to the Sun (perihelion) in its 33-year orbit and we see meteors when the Earth ploughs into this stream of ancient comet debris.

The Leonids was one of the highlights on the meteor calendar not so long ago, with the storm activity from 1999 (2500 meteors per hour were seen for an hour or so) to 2002. This storm and enhanced activity occurs for about five or so years either side of the comet’s perihelion as most of the meteoroids are bunched up in a zone close to the comet. There is a less-dense stream of material spaced out around the whole of the comet’s orbit which produces the meteors we see every year.

Inside the magazine

You can read more about this month’s meteor showers in the November issue of Astronomy Now as part of our complete guide to the night sky. Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s longest running astronomy magazine.