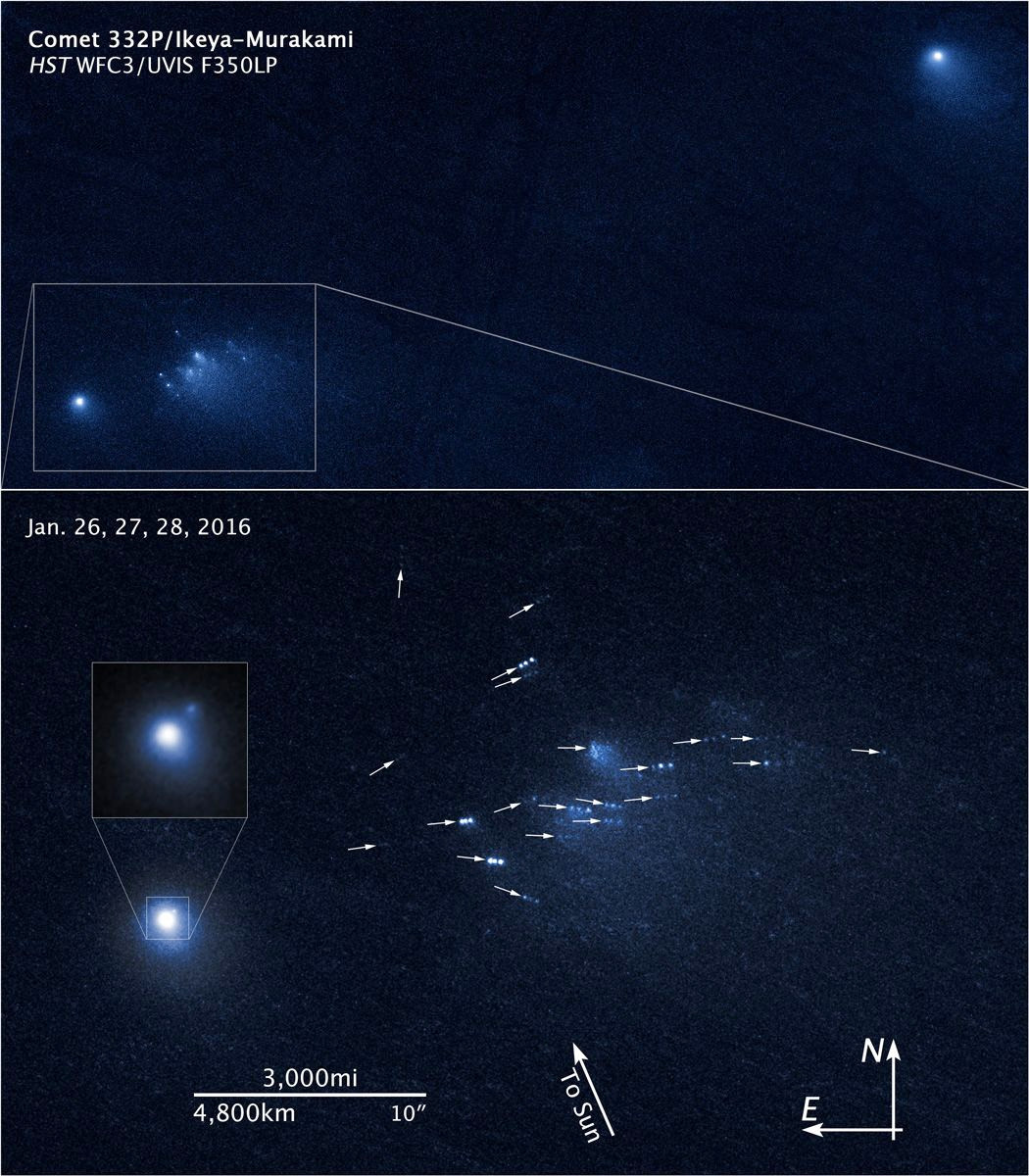

In a series of images taken over three days in January 2016, Hubble showed 25 fragments consisting of a mixture of ice and dust that are drifting away from the comet at a pace equivalent to the walking speed of an adult, said David Jewitt, a professor in the UCLA departments of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences; and Physics and Astronomy, who led the research team.

The images suggest that the roughly 4.5-billion-year-old comet, named 332P/Ikeya-Murakami, or Comet 332P, may be spinning so fast that material is ejected from its surface. The resulting debris is now scattered along a 3,000-mile-long trail, larger than the width of the continental United States.

These observations provide insight into the volatile behaviour of comets as they approach the Sun and begin to vaporise, unleashing powerful forces.

“We know that comets sometimes disintegrate, but we don’t know much about why or how,” Jewitt said. “The trouble is that it happens quickly and without warning, so we don’t have much chance to get useful data. With Hubble’s fantastic resolution, not only do we see really tiny, faint bits of the comet, but we can watch them change from day to day. That has allowed us to make the best measurements ever obtained on such an object.”

The Hubble images show that the parent comet changes brightness frequently, completing a rotation every two to four hours. A visitor to the comet would see the Sun rise and set in as little as an hour, Jewitt said.

The comet is much smaller than astronomers thought, measuring only 1,600 feet (490 metres) across, about the length of five football fields.

Comet 332P was discovered in November 2010, after it surged in brightness and was spotted by two Japanese amateur astronomers.

Based on the Hubble data, the research team suggests that sunlight heated the surface of the comet, causing it to expel jets of dust and gas. Because the nucleus is so small, these jets act like rocket engines, spinning up the comet’s rotation, Jewitt said. The faster spin rate loosened chunks of material, which are drifting off into space. The research team calculated that the comet probably shed material over a period of months, between October and December 2015.

Jewitt suggests that some of the ejected pieces have themselves fallen to bits in a kind of cascading fragmentation. “We think these little guys have a short lifetime,” he said.

That discovery prompted Jewitt and colleagues to request Hubble Space Telescope time to study the comet in detail.

“In the past, astronomers thought that comets die when they are warmed by sunlight, causing their ices to simply vaporise away,” Jewitt said. “But it’s starting to look like fragmentation may be more important. In comet 332P we may be seeing a comet fragmenting itself into oblivion.”

The researchers estimate that comet 332P contains enough mass for 25 more outbursts. “If the comet has an episode every six years, the equivalent of one orbit around the Sun, then it will be gone in 150 years,” Jewitt said. “It’s just the blink of an eye, astronomically speaking. The trip to the inner solar system has doomed it.”

The icy visitor hails from the Kuiper Belt, a vast swarm of objects at the outskirts of our solar system. As the comet travelled across the system, it was deflected by the planets, like a ball bouncing around in a pinball machine, until Jupiter’s gravity set its current orbit, Jewitt said.

A paper on the discovery has just been published online in Astrophysical Journal Letters.