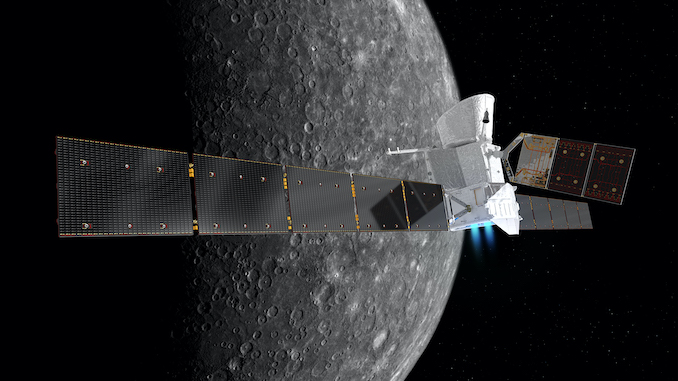

Scientists are still preparing for the crucial fly-by of Earth by the joint European–Japanese BepiColombo mission to Mercury on 10 April, despite the social distancing constraints introduced across the world as the COVID-19 pandemic wreaks havoc.

“The Earth swing-by is a phase where we need daily contact with the spacecraft,” says Elsa Montagnon, who is the BepiColombo Spacecraft Operations Manager at the European Space Agency (ESA). “This is something that we cannot postpone. The spacecraft will swing by Earth independently in any case.”

To reach Mercury, BepiColombo, which was launched on 20 October 2018, must perform numerous fly-bys of various planets, using their gravity to alter its trajectory. Its fly-by of Earth this April is the first of these manoeuvres. Two more will follow at Venus, and then another six fly-bys at Mercury, slowing its velocity sufficiently for BepiColombo to enter into orbit around the innermost planet.

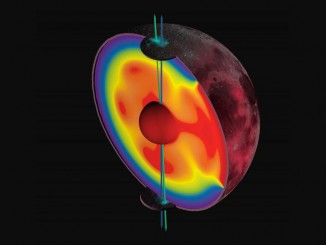

However, the Earth fly-by could not have come at a worse time. As BepiColombo – which is actually composed of three spacecraft, namely ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA’s) Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, and the ESA-built Mercury Transfer Module – heads for a close approach of 12,700 kilometres to Earth, scientists need to upload a number of vital commands. These include preparing the Transfer Module for when the spacecraft moves into eclipse behind Earth and its solar panels are cut off from sunlight. Safety commands also need to be uploaded, should something go amiss with the spacecraft during the fly-by, while it had been hoped that the instruments on the spacecraft could be switched on and calibrated using Earth and the Moon as test objects.

“For example, the [Mercury Planetary Orbiter’s] PHEBUS spectroscope will use the Moon as a calibration target to then produce better data once at Mercury,” says Johannes Benkhoff, who is BepiColombo’s Project Scientist at ESA. “We also want to make some measurements of the solar wind and its interaction with Earth’s magnetic field. The main purpose of having the instruments on at this stage, however, is testing and calibration. If we can use the data for some scientific investigation, it will be a bonus.”

A skeleton crew will work at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, to ensure that the fly-by goes as smoothly as possible, while operating within social distancing restrictions, which will mean limited face-to-face meetings. If the fly-by is successful, as is expected, it will slow BepiColombo, shortening its orbit as it begins its journey into the inner Solar System.

Its next planetary encounter will be at Venus on 15 October this year, with a second fly-by of Venus on 11 August 2021. BepiColombo will then make its first fleeting visit of Mercury on 1 October 2021, performing the first of its six fly-bys there to slow its inward velocity, allowing the spacecraft to slip into Mercury orbit on 5 December 2025.