NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover has finally started drilling into a clay-bearing unit on the lower slopes of Mount Sharp, collecting samples that formed in the presence of water. Reaching this area has been a major objective ever since Curiosity landed in Gale Crater seven years ago.

Back on Earth, meanwhile, engineers in Germany and the United States are carrying out additional tests to figure out what’s preventing a hammer-like device known as “the mole” from pounding into the martian soil near the InSight Mars lander, pulling a string of sensitive temperature sensors along behind it.

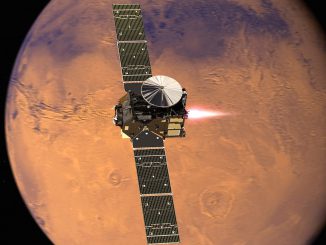

Launched in May 2018, InSight – the acronym stands for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport – landed on Mars last 26 November. It was equipped with just two major instruments: an ultra-sensitive seismometer provided by the French space agency and the German Heat Flow and Physical Properties Probe, or HP3.

The HP3 instrument was designed to use a spring-driven internal hammer-like device – the mole – to pound its way down into the martian soil trailing a cable carrying sensitive temperature sensors.

After some 10,000 hammer blows, the probe was expected to reach a maximum depth of about 5 metres (15 feet). The goal is to measure the thermal conductivity of the soil, helping scientists extrapolate temperatures all the way to the core.

But the mole ran into a sub-surface obstacle of some sort on 28 February after hammering its way just 30 centimetres (1 foot) into the red planet’s soil.

“We are investigating and testing various possible scenarios to find out what led to the ‘mole’ stopping,” said Torben Wippermann, test leader at the DLR Institute of Space Systems in Bremen. Engineers are studying seismic data collected during the initial hammering session to gain insights into what sort of obstacle is blocking the mole from descending farther and studying the effects of different types of sand.

An exact replica of the mole has been sent to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory for additional tests in a simulated Mars surface environment.

“Possible measures to allow the instrument to hammer farther into the ground must … be meticulously tested and analysed on Earth,” the German aerospace agency said in a statement. Hammering is not expected to be attempted again for several weeks.

Curiosity’s more traditional drill had no problem burrowing into the clay-bearing unit at Mount Sharp. In fact, the bedrock chosen for the drill’s first session was so “soft” the device did not have to employ its percussive impactor.

“Curiosity has been on the road for nearly seven years,” said Curiosity Project Manager Jim Erickson. “Finally drilling at the clay-bearing unit is a major milestone in our journey up Mount Sharp.”

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter detected the clay-bearing unit well before Curiosity landed on Mars in 2012. Mission scientists believe samples collected by the rover will shed light on the role of water in the formation of such strata on Mount Sharp.