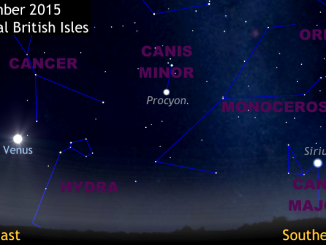

Observers in the UK looking to the south-southeast around 7am GMT on 31 January will see (weather permitting) the old crescent Moon nestled between Venus and Jupiter, but this is merely a line of sight effect: the Moon is the closest of the three at just 396,770 kilometres distant. Next, it’s dazzling Venus – 129.2 million kilometres from Earth. But Jupiter is a staggering 878 million kilometres away on this morning. Put another way, Venus is 326 times farther than the Moon, while Jupiter is 6.8 times farther than Venus on this final dawn of January.

As you contemplate the vastness of the solar system while savouring the view with the naked eye, there’s another treat in store for those with larger binoculars and small telescopes who are prepared to view a little earlier. For most of the British Isles, if you look carefully at the southern (bottom) edge of the Moon close to 6:45am GMT you’ll see a fourth-magnitude star nearby. This is a double known as Xi (ξ) Ophiuchi. It consists of a magnitude +4.4 yellow-white giant primary separated by 3.5 arcseconds from a magnitude +8.9 companion, the pair situated some 57 light-years from Earth.

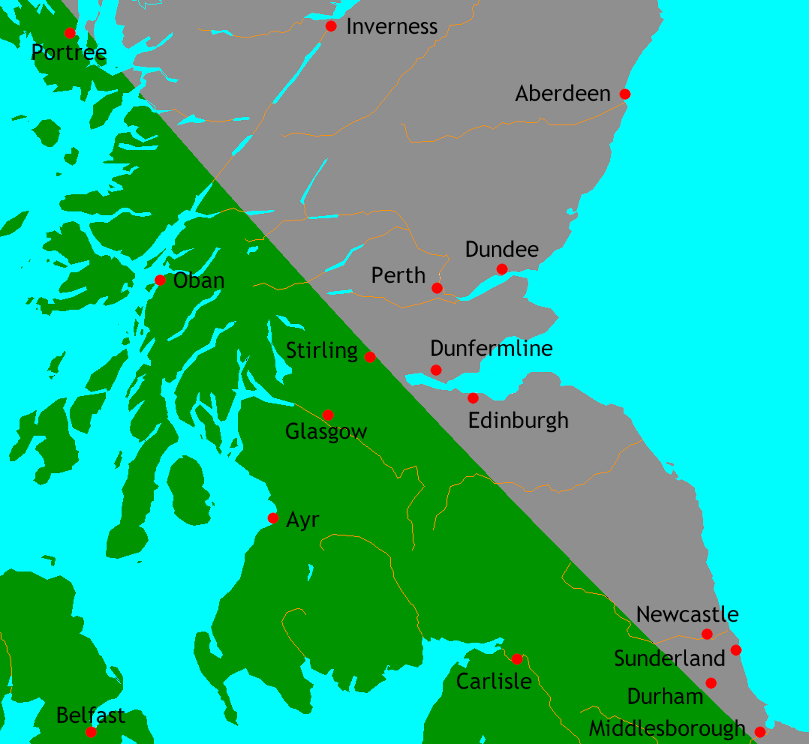

The graze line for the lunar occultation of Xi Ophiuchi on 31 January lies roughly from the Isle of Skye, between Glasgow and Edinburgh through to Scarborough. Anyone in Scotland and northern England located to the north and east of this line will see the occultation, everyone else will not (see the accompanying map extract).

The viewing circumstances for grazing lunar occultations are very localised. For example, observers in Glasgow will see the Moon pass north of Xi Ophiuchi at 6:47:46am, while those in Stirling will see a very near miss at 6:48:14am. However, anyone watching from Edinburgh will see the star disappear at 6:44:56am and reappear at 6:52:44am (all times GMT).

Even if you don’t see Xi Ophiuchi disappear behind the lunar crescent from where you live, do take a look at the juxtaposition of Moon and star close to 6:45am GMT on 31 January. If nothing else you will gain a greater appreciation for just how fast our natural satellite moves in its orbit relative to background stars – roughly one lunar width per hour.