Imagery captured by a sharp-eyed camera aboard a NASA orbiter shows where Europe’s Schiaparelli lander cratered on Mars last week, exploding into fine bits of shrapnel and debris after after an apparent software problem doomed the mission, officials said Thursday.

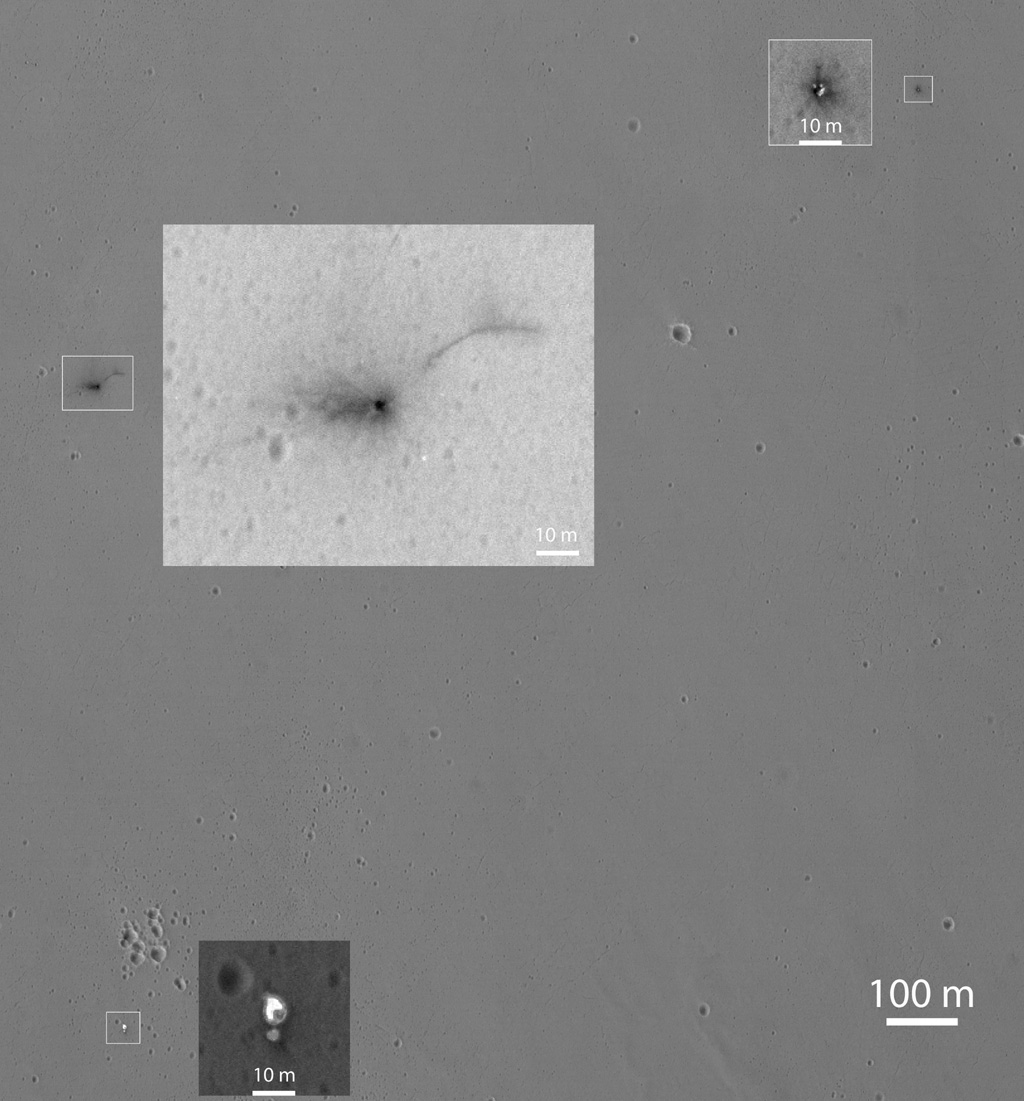

The high-resolution images from the HiRISE camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter reveal new details about Schiaparelli’s fate, showing that the spacecraft likely splintered into countless pieces when it impacted the Martian surface at several hundred kilometres per hour.

A less-detailed image from the context camera on MRO last week showed dark markings attributed to the robotic lander’s high-speed crash, but the latest pictures leave little doubt that the craft exploded on impact, and there is nothing left of Schiaparelli.

Experts measured a central crater in the dark patch to be roughly 2.4 meters across, a size that the European Space Agency said is consistent with the impact of a nearly 300-kilogram object like Schiaparelli. Officials said the crater is predicted to be around 50 centimetres deep.

The dark markings radiate out from the crater in an asymmetric pattern, extending as far as 40 metres in one direction. The asymmetric markings are “difficult to interpret,” ESA said in a statement, and may point to an explosion of Schiaparelli’s hydrazine propellant tanks that threw most of the debris and disturbed soil in one direction.

“In the case of a meteoroid hitting the surface at 40,000-80,000 km/h, asymmetric debris surrounding a crater would typically point to a low incoming angle, with debris thrown out in the direction of travel,” officials wrote in ESA’s press release. “But Schiaparelli was traveling considerably slower and, according to the normal timeline, should have been descending almost vertically after slowing down during its entry into the atmosphere from the west.”

ESA said further analysis is needed to further explain the asymmetric features.

“An additional long dark arc is seen to the upper right of the dark patch but is currently unexplained,” ESA said. “It may also be linked to the impact and possible explosion.”

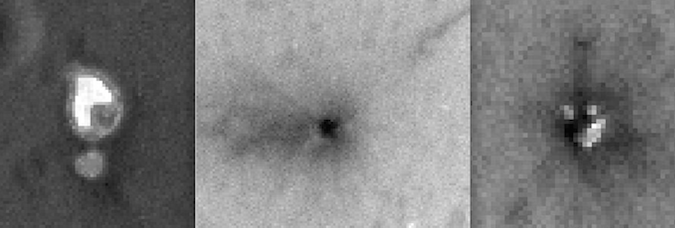

The high-resolution HiRISE image also has a few white dots scattered around the Schiaparelli impact site, but they are too small to be properly resolved.

“These may or may not be related to the impact – they could just be ‘noise,'” ESA said. “Further imaging may help identify their origin.”

Upcoming MRO flyovers will occur with different lighting angles at the crash site in Meridiani Planum, a vast flat plain near the Martian equator, and photos from those passes could tell experts more about potential debris, the depth of Schiaparelli’s crater, and other information.

About 1.4 kilometres south of the main impact site, HiRISE spotted the back part of Schiaparelli’s heat shield and its attached 12-metre supersonic parachute resting intact after they were jettisoned between 2-4 kilometres above Mars, according to ESA.

The back shell and parachute were jettisoned from the descending lander earlier than expected, and Schiaparelli was supposed to fire its nine braking rockets for around 30 seconds to slow the probe’s speed to a walking pace about 2 metres above the surface. At that point, Schiaparelli’s Doppler radar altimeter, feeding altitude and velocity data to the spacecraft’s guidance computer, would help trigger a command to shut off the engines, and the lander was to plop to the surface cushioned by a crushable carbon-fiber shell.

Telemetry from Schiaparelli recorded by ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter, which flew to Mars in tandem with the lander and is reported healthy, told engineers that the thrusters fired for only a few seconds and prematurely shut down.

ESA officials said they also identified the front half of Schiaparelli’s heat shield around 1.4 kilometres east of the main impact site. It fell to the surface after ejecting from the lander as designed about four minutes into the six-minute descent.

While the process to analyze data from Schiaparelli’s descent is still in its early stages, the initial focus of the investigation is on a possible software fault, according to Jorge Vago, project scientist for ESA’s ExoMars program, which includes the Schiaparelli and Trace Gas Orbiter missions that arrived at the red planet 19 October.

“The hardware seems to have all worked well,” Vago wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now. “The problem lies somewhere in the system software interpretation of the various sensors’ inputs.”

A software or computer problem could have led Schiaparelli to believe it was much closer to the ground than in reality, prematurely commanding the separation of its parachute and the shutdown of its braking thrusters.

Engineers last week said the lander’s Doppler radar altimeter activated as planned and collected data for a short time.

“The team is combing through the data with a fine comb to determine exactly what happened,” Vago said.

“Until this full analysis has been completed, there is a danger of reaching overly simple or even wrong conclusions,” ESA cautioned in Thursday’s press release.

The investigation team, including members from ESA and the ExoMars prime contractor Thales Alenia Space, is expected to report its findings by mid-November, ESA said.

Schiaparelli was designed to test landing technologies needed for future European Mars missions, beginning with the ExoMars rover due for launch in July 2020. The Doppler radar altimeter was one such key system to be demonstrated by Schiaparelli.

Engineering data collection was the main goal of the Schiaparelli mission, and the probe achieved many of its objectives in that regard. Jan Woerner, ESA’s director general, said last week that Schiaparelli obtained about 80 percent of the data intended.

If the final touchdown was successful, Schiaparelli would have become the first European spacecraft to successfully land on Mars. An earlier mission — the British-led Beagle 2 lander — reached the Martian surface intact in 2003, but failed to radio home due to a problem after touchdown.

Once landed, Schiaparelli was to turn on a weather station to collect measurements of the temperature, pressure, humidity, and dust in the atmosphere.

Russia is ESA’s main partner on ExoMars, providing Proton launchers for each of the program’s two missions. The Trace Gas Orbiter and Schiaparelli lifted off together on a Proton booster in March, and the rover will fly on another Proton rocket in 2020.

ESA cinched a cooperation agreement with Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, in 2013 after a partnership with NASA fell through. The U.S. space agency, which was to provide two Atlas 5 rockets and a descent stage for the European-built rover, largely backed out of the ExoMars program in 2012 due to budget constraints.

Russia will now build most of the descent stage for the ExoMars 2020 rover, with European industry supplying major components of the vehicle’s guidance system and the flight computer. Roscosmos is also developing a stationary lander that will work on the surface in concert with the European rover.

ESA officials told reporters last week they are optimistic that the ExoMars 2020 mission can go forward as planned, informed by data gathered during Schiaparelli’s landing attempt.

“The same telemetry is also an extremely valuable output of the Schiaparelli entry, descent and landing demonstration, as was the main purpose of this element of the ExoMars 2016 mission,” ESA said in a statement. “Measurements were made on both the front and rear shields during entry, the first time that such data have been acquired from the back heat shield of a vehicle entering the Martian atmosphere.

“The team can also point to successes in the targeting of the module at its separation from the orbiter, the hypersonic atmospheric entry phase, and the parachute deployment at supersonic speeds, and the subsequent slowing of the module,” ESA said.

The Trace Gas Orbiter — the primary component of the ExoMars 2016 mission — is functioning normally after its successful maneuver to entire orbit around Mars last week.

The satellite is the sixth orbiter currently operating at Mars, joining NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, MAVEN atmospheric observatory and Mars Odyssey spacecraft, ESA’s Mars Express, and India’s Mars Orbiter Mission.

The Trace Gas Orbiter carries sensors to measure trace constituents in the Martian atmosphere such as methane, which scientists believe could be a marker for living microbes or ongoing geological activity on Mars. The spacecraft will also look for water resources hidden just below the top layer of Mars’ soil, and collect imagery to update and improve maps of the red planet.

The first measurements and images from the Trace Gas Orbiter will come around 20 November to help scientists calibrate the craft’s instruments.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.