Sunlight reaching Earth efficiently heats the terrestrial atmosphere at altitudes well above the surface — even at 250 miles high, for example, where the International Space Station orbits. Jupiter is over five times more distant from the Sun, and yet its upper atmosphere has temperatures, on average, comparable to those found at Earth. The sources of the non-solar energy responsible for this extra heating have remained elusive to scientists studying processes in the outer solar system.

“With solar heating from above ruled out, we designed observations to map the heat distribution over the entire planet in search for any temperature anomalies that might yield clues as to where the energy is coming from,” explained O’Donoghue, a research scientist at BU.

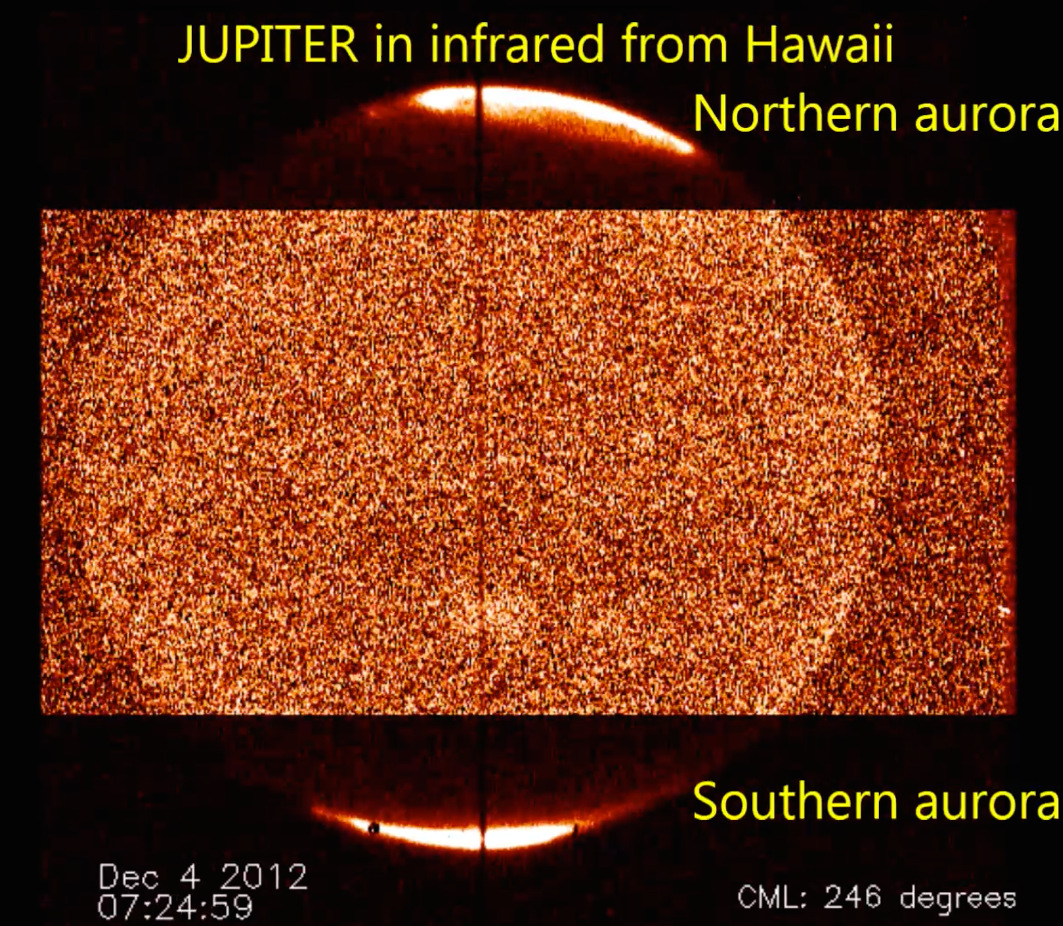

Astronomers measure the temperature of a planet by observing the non-visible, infrared (IR) light it emits. The visible cloud tops we see at Jupiter are about 30 miles above its rim; the IR emissions used by the BU team came from heights about 500 miles higher. When the BU observers looked at their results, they found high altitude temperatures much larger than anticipated whenever their telescope looked at certain latitudes and longitudes in the planet’s southern hemisphere.

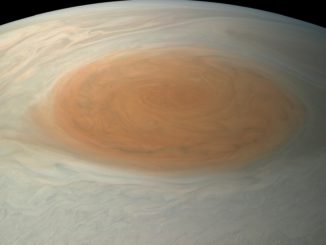

“We could see almost immediately that our maximum temperatures at high altitudes were above the Great Red Spot far below — a weird coincidence or a major clue?” O’Donoghue added.

“The Great Red Spot is a terrific source of energy to heat the upper atmosphere at Jupiter, but we had no prior evidence of its actual effects upon observed temperatures at high altitudes,” explained Dr. Luke Moore, a study co-author and research scientist in the Center for Space Physics at BU.

Solving an “energy crisis” on a distant planet has implications within our solar system, as well as for planets orbiting other stars. As the BU scientists point out, the unusually high temperatures far above Jupiter’s visible disc is not a unique aspect of our solar system. The dilemma also occurs at Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, and probably for all giant exoplanets outside our solar system.

“Energy transfer to the upper atmosphere from below has been simulated for planetary atmospheres, but not yet backed up by observations,” O’Donoghue said. “The extremely high temperatures observed above the storm appear to be the ‘smoking gun’ of this energy transfer, indicating that planet-wide heating is a plausible explanation for the ‘energy crisis.'”

O’Donoghue cites the help of the Royal Astronomical Society, when he was a PhD student, as being crucial to starting the work. “A £500 travel grant from the RAS, at a time of very tight funding, made it possible for me to carry out the observations on the SpeX instrument, mounted on the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility on Hawaii. This modest support helped me start my career in astronomy, which has taken me to Boston, and seen me publish my work in the world’s leading scientific journals.”

Co-author Dr. Henrik Melin from the University of Leicester said: “Jupiter is a hot topic with Juno having just entered orbit at the planet. Leicester is home to the only UK group that is formally involved in this mission, and are directly involved with preparations for the JUICE mission, to be launched in 2022. We are very excited about the new science that these missions will bring.”

Dr. Tom Stallard, also from Leicester, and another co-author, added: “Our coordinated telescope observations of Jupiter are providing a global context to these space missions. This fantastic result, showing how the upper atmosphere is heated from below, was produced directly from Leicester’s 2012 observing campaign, which was designed to try and answer why Jupiter’s upper atmosphere is so hot. Juno will be measuring the aurora and its sources, and we expected the auroral energy to flow from the pole to the equator. Instead, we find the equator appears to be heated from plumes of energy coming from Jupiter’s vast equatorial storms.”