Seeing Jupiter from the UK

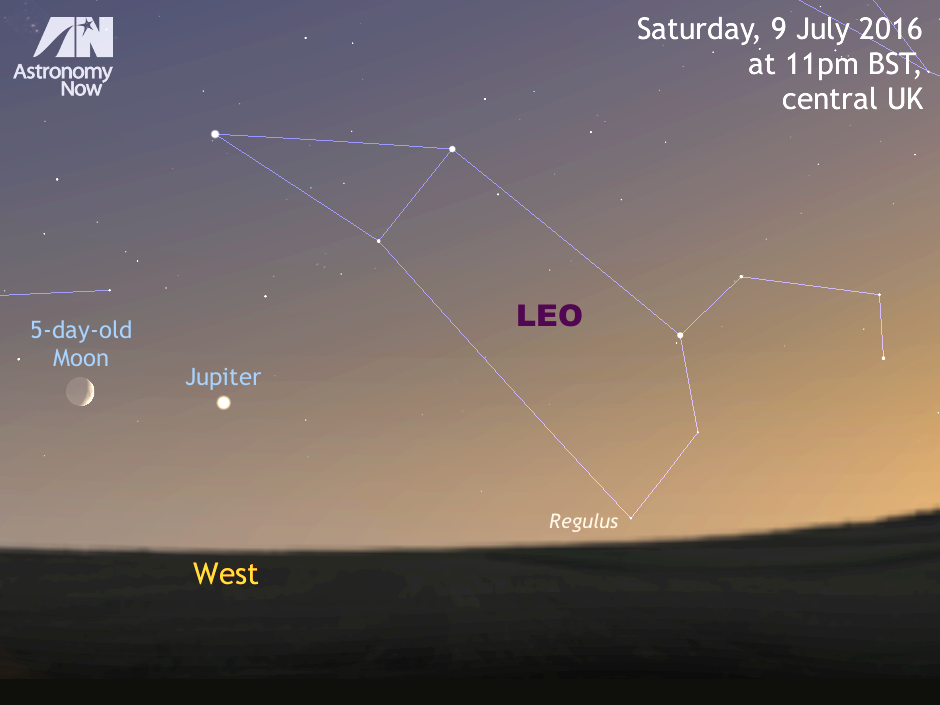

For observers in the British Isles wishing to see Jupiter with the naked eye, the magnitude -1.8 planet lies in the constellation of Leo and sets in the west close to midnight around the end of the first week of July. By the time the sky is dark enough to see Jupiter — which is about 11pm for much of the UK — the planet will be just 7 degrees (or three-quarters of the span of a fist held at arm’s length) above the horizon, due west. On the night of Saturday, 9 July, the 5-day-old crescent Moon lies just 6 degrees to the left of Jupiter, so the pair can be seen in the same field of view of low-power binoculars.

In the Southern Hemisphere, observing prospects for the 9 July Moon-Jupiter conjunction are much better. As seen from Sydney, Australia, Jupiter can be found just two lunar diameters away from the Moon, some 37 degrees high in the northwestern sky as night falls around 6:30pm local time. By 9pm AEST in southeast Australia, the setting Moon and Jupiter will be about 0.6 degrees apart and make a spectacular pairing in telescopes magnifying 50x or less. For observers in the southern Indian Ocean, the Moon actually occults Jupiter close to 10:00 UTC.

Hopefully weather conditions will be fine for you to gaze upon Jupiter and the Moon on 9 July. If you are fortunate enough to see them close together in the same field of view of an optical instrument — or merely with the naked eye — reflect on the knowledge that Jupiter is 546 million miles (879 million kilometres) from Earth on the night in question, some 2,200 times further away than the adjacent Moon. Despite having a physical diameter 40 times that of our Moon, Jupiter requires a magnification of 54x to enlarge it to the same size as the Moon appears to the unaided eye on 9 July.

Inside the magazine

Find out more about observing Jupiter and the other planets currently in the night sky in the July 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.