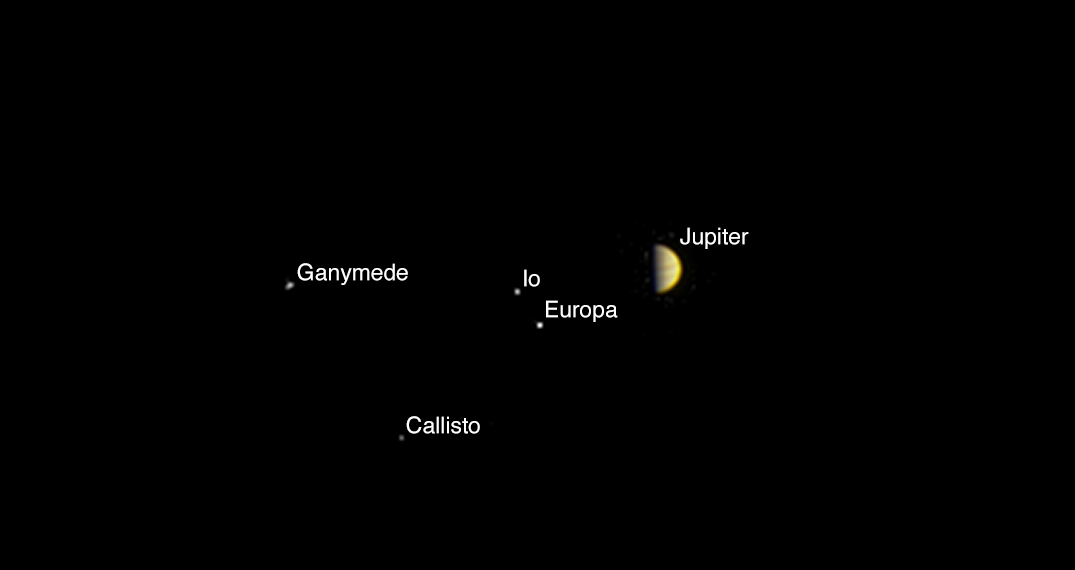

The visible camera on NASA’s Juno spacecraft is capturing a time-lapse movie of Jupiter and its four largest moons as the orbiter dives toward the giant planet for a 4 July rendezvous, and officials have released a first taste of the views armchair scientists and space enthusiasts can anticipate over the coming weeks and months.

The JunoCam instrument aboard Juno captured the colour view of Jupiter and its moons Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto on 21 June at a distance of 10.9 million kilometres (6.8 million miles) from Jupiter. NASA released the picture Friday.

The golden hues of Jupiter’s atmospheric bands are just coming into view, and JunoCam will resolve more detail in the coming days.

Derived from a descent imager carried by NASA’s Curiosity rover to Mars, JunoCam will gather hundreds of pictures during Juno’s 20-month mission at Jupiter.

A few of the images, such as views collected during Juno’s approach to Jupiter this month, are part of Juno’s main science campaign and pre-selected by researchers on the mission team. Officials will string together a sequence of images taken by JunoCam this month into a time-lapse movie showing the celestial dance of Jupiter and its moons as Juno dives toward the giant planet’s north pole.

No such view has ever been seen before.

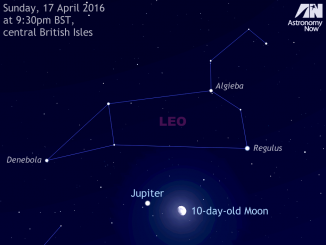

“We’ve had a number of spacecraft that have flown past Jupiter and taken pictures and taken movies, but they have always been in the equatorial plane,” says Candice Hansen from the Planetary Science Institute, a member of Juno’s science team responsible for planning the mission’s camera operations. “This mission is the first one where we really get up over the polar regions.”

Like Juno’s other scientific sensors, JunoCam will be turned off 29 June, five days before the spacecraft’s arrival for a make-or-break engine burn to enter orbit around the planet.

JunoCam’s primary purpose is as a public outreach tool, and Juno managers plan to solicit suggestions from the public for the camera’s imaging targets.

The camera will be tasked to take pictures of cloud patterns and storms identified by amateur astronomers, who can upload their views of Jupiter to a section of the Juno mission website. Then members of the public can collaborate and vote on which regions of Jupiter should be imaged by JunoCam, and enthusiasts can process the raw image data on their own computers at home.

JunoCam works by taking pictures in a series of lines, with its detector scanning Jupiter’s cloud tops in steps as the Juno spacecraft rotates once every 30 seconds. JunoCam is designed to collect components of the final image at the correct rate to avoid smear as the Juno spacecraft zooms about 5,000 kilometres (3,100 miles) over Jupiter’s cloud tops.

Juno will fly in a long, looping orbit around Jupiter, taking it as far as about 3 million kilometres (2 million miles) from the planet on each circuit. At such distances, JunoCam will not be able to resolve much detail on Jupiter’s surface, so scientists have asked the amateur astronomy community to supply contextual imagery to help plan the camera’s targets when the spacecraft is closer to the planet.

NASA says each close approach to Jupiter — called a perijove — will produce about a dozen JunoCam images, along with a wealth of other data gathered by the mission’s other instruments, which are focused on sounding of the planet’s atmospheric layers, measurements of its gravitational and magnetic fields, and surveying its radiation environment.

At least 37 orbits are in Juno’s flight plan. That includes a few laps around Jupiter just arrival its arrival in July set aside for engineering tests and manoeuvres, plus a spare orbit at the end of the mission to fill in any missing data gaps.

“The whole theme is to do science in a fishbowl,” says Hansen. “Let’s do what we would do, but let’s do it in a public forum so that the public can participate.”

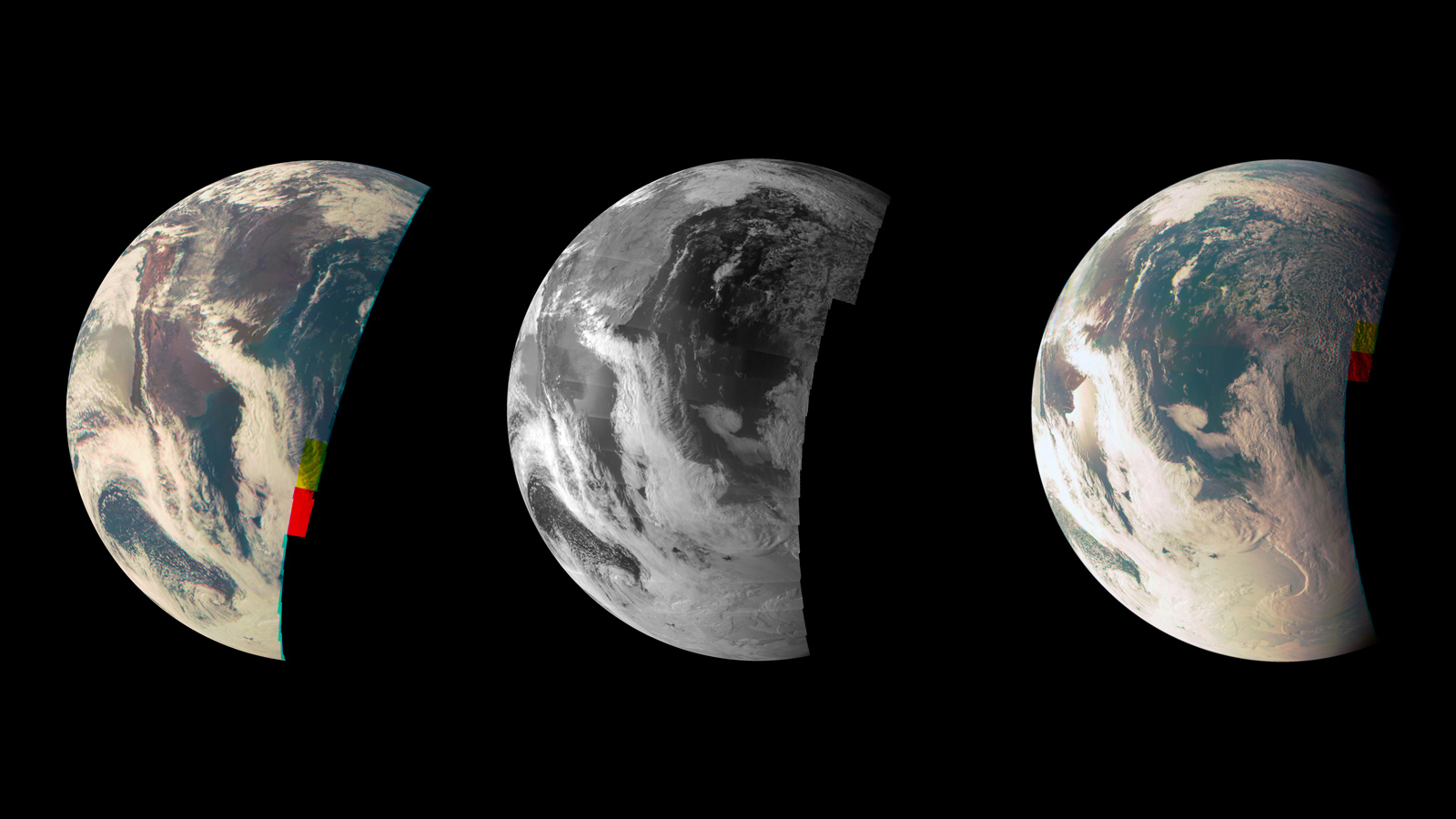

Scientists tested JunoCam when the spacecraft re-visited Earth in October 2013 for a gravity assist to head out toward Jupiter. Amateur image analysts processed the camera’s raw data to produce images of cloud-covered Patagonia, proving the performance of the camera and the public outreach operations concept.

Readers interested in participating in JunoCam’s campaign of exploration should visit the Juno mission website.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.