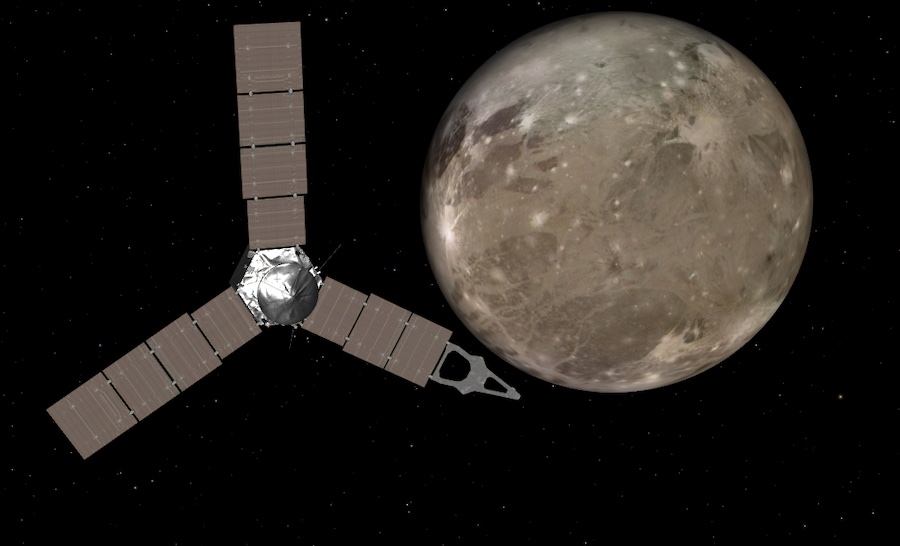

NASA’s Juno spacecraft flew by Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, Monday on the first close-up visit to the icy world since 2000.

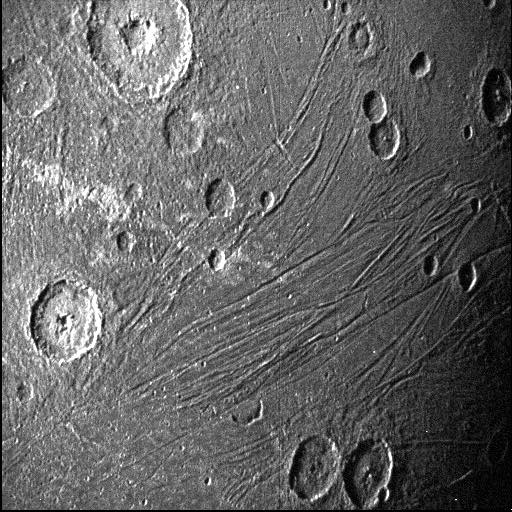

The first images from the flyby show Ganymede’s cratered, icy surface in “remarkable detail,” NASA said. The moon is covered in patches of dark and bright terrain, with long, stripe-like grooves and ridges also visible. Scientists say the linear features could be linked to tectonic faults.

The solar-powered Juno spacecraft’s JunoCam imager and navigation camera took pictures as the orbiter zipped by Ganymede at 1735 GMT Monday at a distance of about 1,038 kilometres (645 miles).

“This is the closest any spacecraft has come to this mammoth moon in a generation,” said Scott Bolton, the Juno mission’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “We are going to take our time before we draw any scientific conclusions, but until then we can simply marvel at this celestial wonder — the only moon in our solar system bigger than the planet Mercury.”

During the speedy flyby, Juno passed Ganymede at a speed of more than 19 kilometers per second (40,000 mph).

In addition Juno’s scientific observations, the encounter used Ganymede’s gravity to shrink the period of spacecraft’s oval-shaped orbit around Jupiter from 53 days to 43 days, setting up for a flyby with Europa in September 2022, and flybys with the volcanic moon Io in 2023 and 2024.

Juno is on an extended mission orbit around Jupiter, where it arrived July 4, 2016, to study the giant planet’s atmosphere, magnetic field, and internal structure. The robotic mission launched 5 August 2011 from Cape Canaveral aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

The JunoCam instrument’s visible light camera viewed almost an entire side of Ganymede during the flyby Monday. The first views returned to Earth show a black-and-white view of the icy moon, the largest in the solar system and the only moon with its own magnetic field. Future data downlinks allow imaging experts to create a colour portrait of Ganymede, according to NASA.

Juno’s Stellar Reference Unit, part of the spacecraft’s navigation system, captured a view of the night side of Ganymede. The light-sensitive camera resolved the moon’s surface illuminated by dim light scattered off Jupiter.

NASA said the JunoCam view of Ganymede has a resolution of about 1 km (0.6 miles). The high velocity Juno’s encounter with Ganymede meant there was enough time for JunoCam to take five images.

The navigation camera image resolution is between 0.37 to 0.56 miles (600 to 900 meters) per pixel.

“The conditions in which we collected the dark side image of Ganymede were ideal for a low-light camera like our Stellar Reference Unit,” said Heidi Becker, Juno’s radiation monitoring lead at JPL. “So this is a different part of the surface than seen by JunoCam in direct sunlight. It will be fun to see what the two teams can piece together.”

Juno’s ultraviolet spectrograph, Jovian infrared auroral mapper, and microwave radiometer were active during the Ganymede flyby to measure the composition, thickness, and temperature of the moon’s water-ice crust. Juno was also tuned to measure the radiation environment around Ganymede, collecting data to benefit future missions to study Jupiter and its moons.

Bolton said Tuesday that the Juno spacecraft, built by Lockheed Martin, executed the flyby sequence as planned.

Scientists believe Ganymede harbors an underground saltwater ocean. Evidence gathered during observations of Ganymede’s aurorae with the Hubble Space Telescope showed the light displays “rocking” back and forth, revealing insights about the moon’s magnetic field. Scientists can infer assumptions about Ganymede’s interior from the magnetic field measurements.

A shell of water ice, likely with rock mixed in, covers Ganymede’s buried ocean, which scientists think contains more water than all the water on the surface of Earth.

The last mission to explore Jupiter’s moons was Galileo, a NASA spacecraft that orbited Jupiter from 1995 until 2003. Galileo’s last close flyby with Ganymede occurred May 20, 2000.

NASA’s Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes also observed Ganymede and Jupiter’s other large moons during a pair of flybys in 1979.

Juno’s science team will compare the fresh images of Ganymede with views captured by previous missions. Scientists will look for changes in Ganymede’s surface, such as fresh craters, which could help astronomers better understand the population of objects that impact moons in the outer solar system, according to NASA.

Juno’s flyby of Ganymede offers a taste of what’s to come with the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or JUICE, mission set for launch next year. The robotic JUICE spacecraft will arrive in orbit around Jupiter in 2029, perform flybys of several of Jupiter’s moons, then enter orbit at Ganymede in 2032.

On Tuesday, Juno completed its 33rd close science pass of Jupiter, reaching the closest point in its elongated orbit around the giant planet.

Jupiter’s asymmetric gravity field is gradually perturbing Juno’s trajectory and pulling the closest point of the spacecraft’s orbit northward over time. The shift in Juno’s orbit will allow the spacecraft to get a better view of Jupiter’s North Pole, and also enables the flybys of Ganymede, Europa, and Io.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.