Mercury’s orbital period is just 88 days, but as seen from our moving vantage point on Earth the planet comes between us and the Sun (termed inferior conjunction) every 116 days, on average. Most times Mercury passes above or below the Sun’s disc, but 13 or 14 times every century, in the months of May or November when the orbits of Earth and Mercury align, the planet can be seen to pass directly in front of our nearest star.

Although Mercury is at its closest to Earth at inferior conjunction, it still lies some 52 million miles (82 million kilometres) distant at the middle of this transit. Given Mercury’s diameter of 3032 miles (4879 kilometres), this means that the planet will appear as a jet black circular silhouette just 12.1 arcseconds across, or 1/157th that of the Sun’s diameter.

As seen through special eclipse sunglasses, Mercury will therefore be too small to see without optical aid. Even the pinhole projectors that worked successfully for the solar eclipse in March 2015 will not be of any use as Mercury will still be too small to be visible.

A caveat for binocular and telescope users

To see Mercury in transit, one must therefore use a binocular or a telescope. make no apologies for repeating the warning to never look at the Sun through an unfiltered optical instrument, even when it is low in the sky (as at the conclusion of this transit seen from the UK) or heavily obscured by mist or fog. The Sun may seem to be of a safe intensity, but the telescope will still concentrate harmful infrared and ultraviolet light that will damage your eyesight. Furthermore, clouds can break in an instant and glimpsing the Sun — even for a fraction of a second — can cause instant and irreparable eye damage.

The British Astronomical Association (BAA) has produced an excellent online guide to viewing this transit safely.

Point the telescope or binocular at the Sun by noting when its shadow appears smallest on the projecting card. You can then improve contrast in the projected image by positioning a cardboard sunshade close to the front of the telescope or binocular. A good size for a projected solar image is 100—150mm (4—5″), which will show Mercury as a millimetre-sized dot. Sunspots may also be visible, but Mercury will appear darker and have a more sharply defined edge than these.

If you are unsure as to the orientation of your projected solar image, remember that the rotation of the Earth carries the Sun from celestial east to west; you will periodically have to nudge your tripod-mounted binoculars to keep the Sun centred on the card. An equatorially-mounted telescope with a motor drive or slow motion controls will make this much easier.

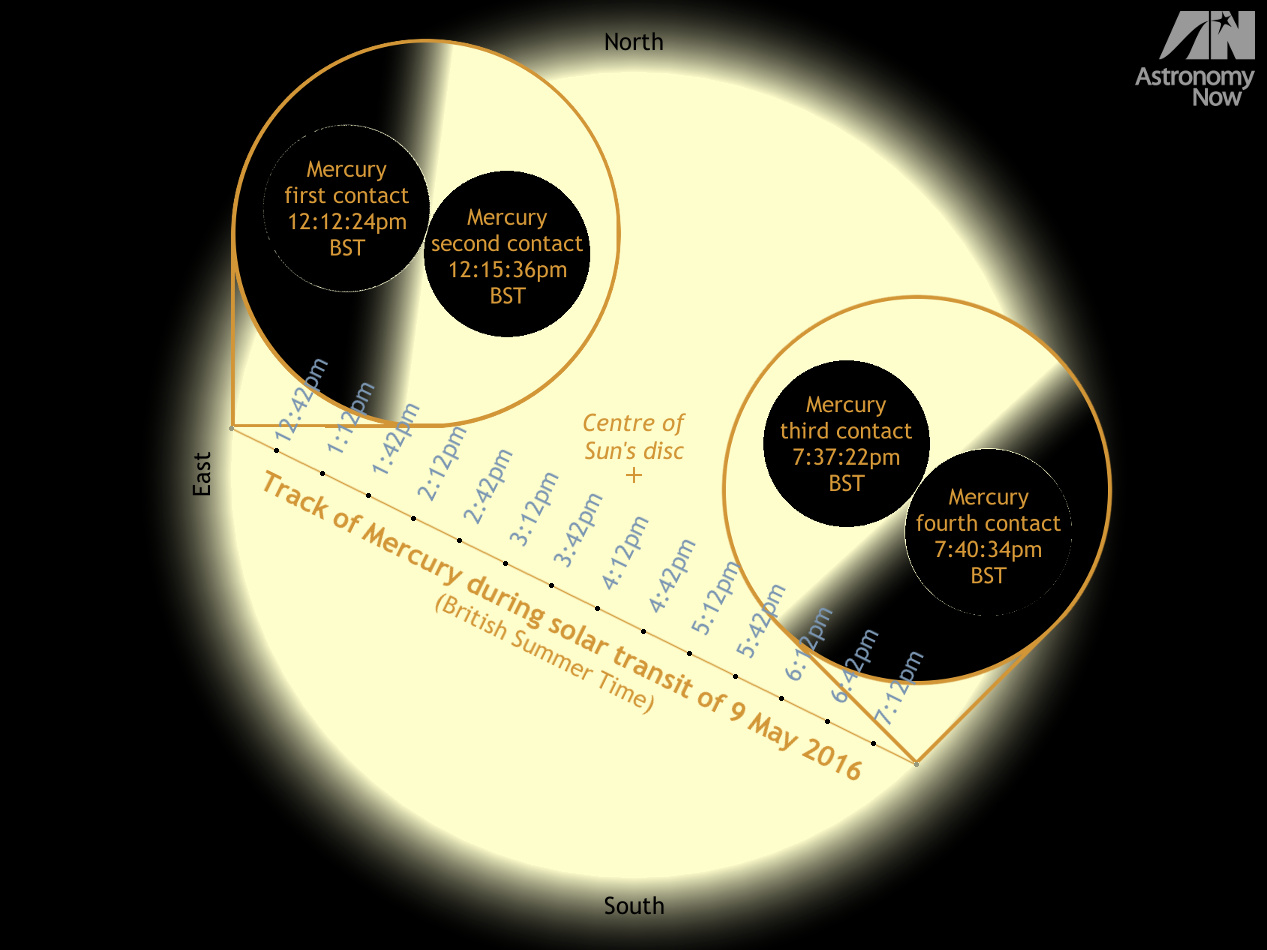

Owing to parallax, observers in different locations on Earth will see the transit taking place at a slightly different time, as Mercury will appear to take a slightly different path across the Sun. All subsequent times in this article are expressed in British Summer Time for an observer at the centre of the country, but they will differ by no more than a few seconds wherever you may be in the UK.

- 12h12m24s pm — First Contact

This is when we see the first ‘bite’ out of the limb (edge) of the Sun as Mercury glides into view. It may also be possible to see the ‘black drop’ effect, where a broad line appears to connect the planet to the solar limb. As seen from the centre of the UK, Mercury (α=03h 07.4m, δ=+17° 30′ J2000.0) lies 52 degrees high in the south-southeast. - 12h15m36s pm — Second Contact

Some 3.2 minutes after Mercury’s first appearance, the planet is now seen in full silhouette against the solar photosphere. - 03h56m20s pm — Greatest Transit

As seen from the heart of the British Isles, Mercury (α=03h 07.1m, δ=+17° 26′ J2000.0) is halfway through its transit of the Sun. The planet is now 41 degrees high in the southwest as seen from the centre of the UK. - 07h37m22s pm — Third Contact

Mercury is tangential to the solar limb, poised to leave the Sun’s disc. The planet (α=03h 06.7m, δ=+17° 22′ J2000.0) is now just 10 degrees high in the west as seen from heart of the UK. - 07h40m34s pm — Fourth Contact

Mercury finally glides off the face of the Sun, concluding this solar transit.

Future transits of Mercury

Given the favourable aspect of this transit as seen from the British Isles, one would be very unlucky not to see at least a fleeting glimpse of Mercury through a correctly filtered telescope between scudding clouds in the 7½-hour duration of this event. However, should you be completely clouded out, you only have to wait until 11 November 2019 for the next. Unfortunately, the 2019 transit is only partly seen from the UK; the next transit of Mercury wholly visible from the British Isles occurs on 7 May 2049!

But I don’t have a telescope or a binocular!

If you don’t have an optical instrument, or you left it too late to buy your solar filter, don’t fret — there’s a high probability that one of the many transit-viewing activities organised nationwide listed in this story is happening near you. Clear skies everyone!

Inside the magazine

Find out all you need to know about observing Mercury safely during the transit and the other solar system bodies currently in the night sky in the May 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.