The findings were announced today during a news briefing at the 227th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) being held this week in Kissimmee, Florida.

Supermassive black holes exist at the centers of all massive galaxies, including the Milky Way, and contain a mass of between one million and one billion times that of our Sun. The mass of a black hole tends to scale with the mass of its galaxy, and each black hole is typically embedded in a large sphere of stars.

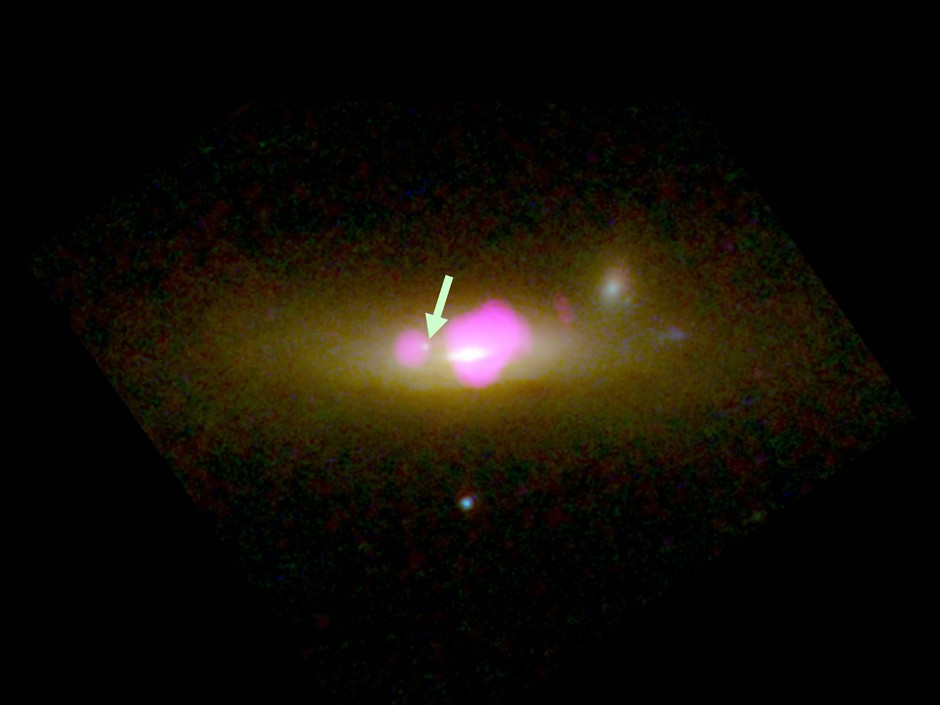

The galaxy SDSS J1126+2944 is the result of a merger between two smaller galaxies, which brought a pair of supermassive black holes into SDSS J1126+2944. One of the black holes is surrounded by a typical amount of stars, but the other black hole is strangely “naked” and has a much lower number of associated stars than expected.

“One black hole is starved of stars, and has 500 times fewer stars associated with it than the other black hole,” said Julie Comerford, an assistant professor in CU-Boulder’s Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences and the lead investigator of the new research. “The question is why there’s such a discrepancy.”

One possibility, said Comerford, is that extreme gravitational and tidal forces simply stripped away most of the stars from one of the black holes over the course of the galactic merger. In other words, the black hole went on a crash diet and shed most of its stars.

The other possibility, however, is that the merger actually reveals a rare “intermediate” mass black hole, with a mass of between 100 and one million times that of our Sun. Intermediate mass black holes are predicted to exist at the centres of dwarf galaxies and thus have a lower number of associated stars. These intermediate mass black holes can grow and one day become supermassive black holes.

“Theory predicts that intermediate black holes should exist, but they are difficult to pinpoint because we don’t know exactly where to look,” said Scott Barrows, a postdoctoral researcher at CU-Boulder who is a co-author on the study. “This unusual galaxy may provide a rare glimpse of one of these intermediate mass black holes.”

If galaxy SDSS J1126+2944 does indeed contain an intermediate black hole, it would provide researchers with an opportunity to test the theory that supermassive black holes evolve from these lower-mass ‘seed’ black holes.