The long-awaited fly-by of Pluto by the New Horizons spacecraft, on 14 July 2015, was an event 85 years in the making, following Pluto’s discovery by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. Since then, Pluto has gone from planet to dwarf planet, but despite protestations from the New Horizons team, its reclassification never really changed the mission or the importance of what it would find at Pluto.

The year began with New Horizons 220 million kilometres from Pluto, but with the dwarf planet in sight. “After travelling more than nine years through space, it’s stunning to see Pluto, literally a dot of light as seen from Earth, becoming a real place right before our eyes,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons’ Principal Investigator.

The search for new moons

As the world counted down the days and months to the fly-by, the focus was on the search for more moons to add to the five already known around Pluto. The four smallest moons, named Styx, Hydra, Nix and Kerberos, are all believed to have been blasted off Pluto in an ancient impact and, given that theory, it was quite possible that other small moons existed, along with belts of dusty debris that could have threatened New Horizons as it raced through the Plutonian system. Yet no new moons were found.

“Not finding new moons or rings present… [was] a bit of a scientific surprise to most of us”, said Stern. Further investigations with the Hubble Space Telescope ahead of the fly-by revealed that Nix and Hydra tumble chaotically through space, perturbed by the shifting gravitational fields of Pluto and Charon, the largest of Pluto’s moons.

“Like good children, our Moon and most others keep one face focused attentively on their parent planet, [but] what we’ve learned is that Pluto’s moons are more like ornery teenagers who refuse to follow the rules”, said Douglas Hamilton of the University of Maryland.

The fly-by

Anticipation had grown to fever pitch by the day of the fly-by. The large distance to Pluto incurred a significant time lag that meant that it was impossible to follow the mission in real time. All the New Horizons team could do was sit back and wait for a signal, all the time hoping that the fly-by, which brought New Horizons within 12,500 kilometres of Pluto, had been performed correctly. When the very first close-up images of Pluto were downloaded from the spacecraft to Earth, they were worth the 85-year wait.

“[New Horizons] has had nine years to build expectations about what we would see during closest approach to Pluto and Charon. Today, we get the first sampling of the scientific treasure collected during those critical moments, and I can tell you it dramatically surpasses those high expectations,” said John Grunsfeld, NASA’s Associate Administrator for the agency’s science missions, upon seeing the first images.

An active world

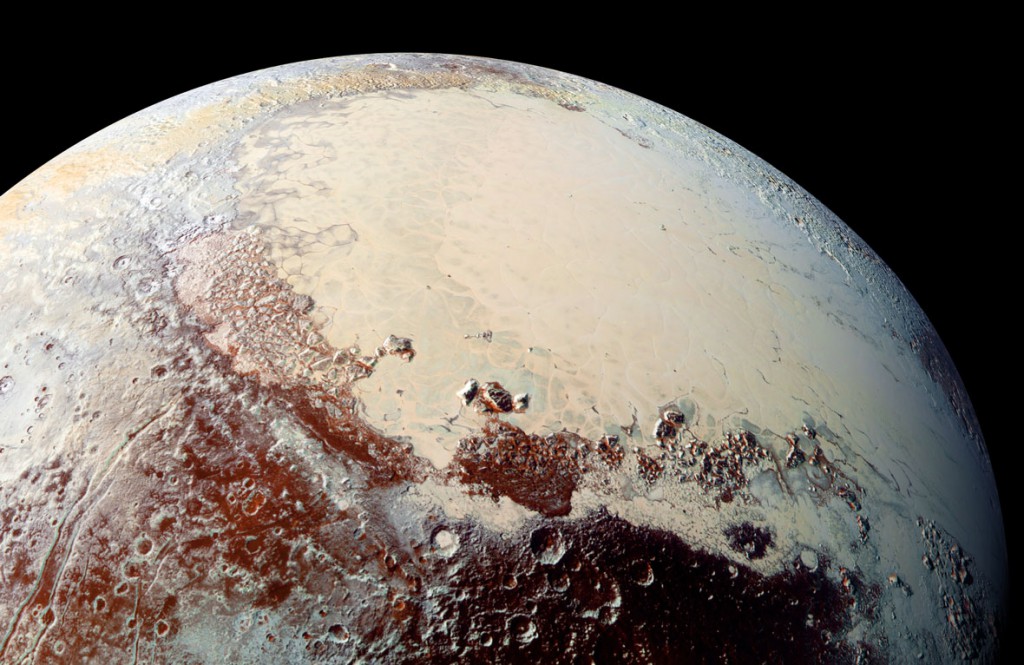

With the fly-by being so brief, New Horizons was unable to view the entirety of Pluto’s surface. What it did see was a land of mountains and gorges, hummocky craters and smooth plains of ice, including the vast, heart-shaped ‘Tombaugh Regio’ and its western-lobe, ‘Sputnik Planum’. Despite its distance from the Sun, Pluto certainly did not give any indication that it was a dead world – its varied surface was a clear signal of the presence of geological activity.

“[Pluto’s] is one of the youngest surfaces we’ve ever seen in the Solar System,” said Jeff Moore of NASA’s Ames Research Center. “This terrain is not easy to explain. The discovery of vast, crater-less, very young plains on Pluto exceeds all pre-fly-by expectations.”

“At Pluto’s temperatures [–234 degrees Celsius]… these ices can flow like a glacier,” said Bill McKinnon of Washington University in St Louis. “In the southernmost region of Sputnik Planum, adjacent to the dark equatorial region, it appears that ancient, heavily-cratered terrain has been invaded by much newer icy deposits.”

“We did not expect to find hints of a nitrogen-based glacial cycle on Pluto operating in the frigid conditions of the outer Solar System,” adds Alan Howard of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. “Driven by dim sunlight, this would be directly comparable to the hydrological cycle that feeds ice caps on Earth, where water is evaporated from the oceans, falls as snow, and returns to the seas through glacial flow.”

A hazy view

New Horizons also discovered activity in the atmosphere above Pluto’s surface, particularly when viewing the dwarf planet in backlit images that clearly showed a dozen or so layers of haze, made from hydrocarbon particles produced by ultraviolet light from the Sun that breaks apart methane. These haze particles then slowly drift down to freeze out onto the surface.

“The hazes detected… are a key element in creating the complex hydrocarbon compounds that give Pluto’s surface its reddish hue”, said Michael Summers of George Mason University in Virginia.

“In addition to being visually stunning, these low-lying hazes hint at the weather changing from day to day on Pluto, just like it does here on Earth”, said Will Grundy, from Lowell Observatory in Arizona.

“Pluto is surprisingly Earth-like in this regard”, added Stern. “And no one predicted it.”

Inside the magazine

Our top ten greatest stories of 2015 first appeared in the December edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest and best astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.