Previous studies have looked for groupings of these stellar giants by seeking out concentrations of them in 2-D projections. Astronomers use these 2-D projections to look at the position and velocity of the stars in a given region and pick out stars that are moving together, and are thus most likely members of the same stellar group.

“Mapping data from missions like Hipparcos in two dimensions has allowed us to identify and classify numerous stellar groups and has profoundly changed our knowledge and understanding of the solar vicinity,” explains Hervé Bouy from the Center for Astrobiology (CSIC-INTA), Spain, lead author of the study. “But it comes with significant drawbacks. 2-D projections are just not capable of describing all the features of 3-D space and using them to model distributions can cause artificial structures to appear and important structures to be hidden in the projection and lost.”

Among other drawbacks, all 2-D projection methods, including those not described here, can be affected by the presence of companion stars. Binary stars — two stars which orbit one another — can interfere with measurements of the motion of the stars in a group causing smaller or less tightly bound groups to be missed when searching for them solely on the basis of their common motion. In this study, rather than project the data onto a series of 2-D planes, the astronomers used the measured distances to O and B type stars in the data to map the density and position of the stars in three dimensions. The 3-D data analysis and interactive visualisation techniques used in this study, combined with a lack of reliance on velocities as a discovery criterion for the stellar groups, led to several discoveries that had been missed in 25 years of 2-D analysis of the data.

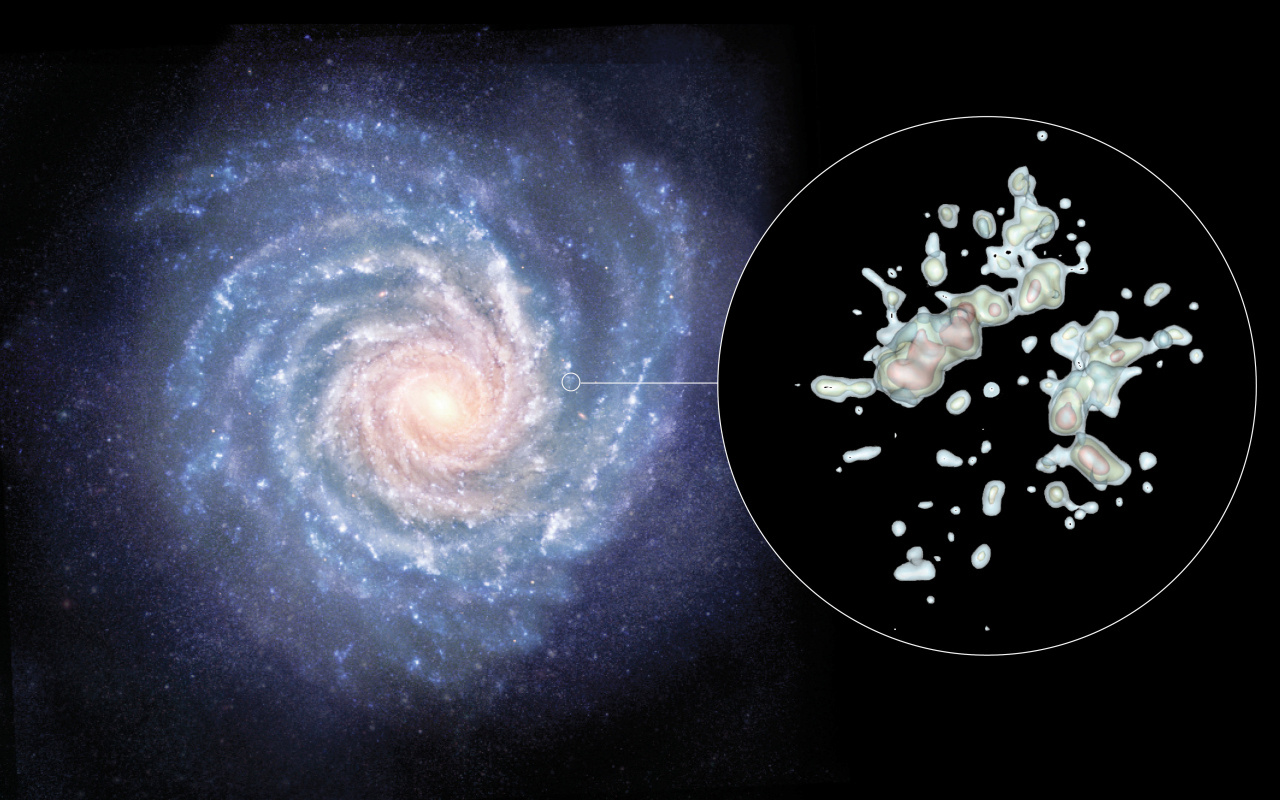

“Our study has shown just how different the architecture of the solar neighbourhood looks when mapped in three dimensions,” explains João Alves from the University of Vienna, Austria, co-author of the paper. “We have produced a 3-D visualisation of all of the Hipparcos O and B type stars within around 1500 light-years of the Sun and in doing so have found evidence for new structures in the distribution of nearby hot stars, and new and surprising theories of how those stars formed.”

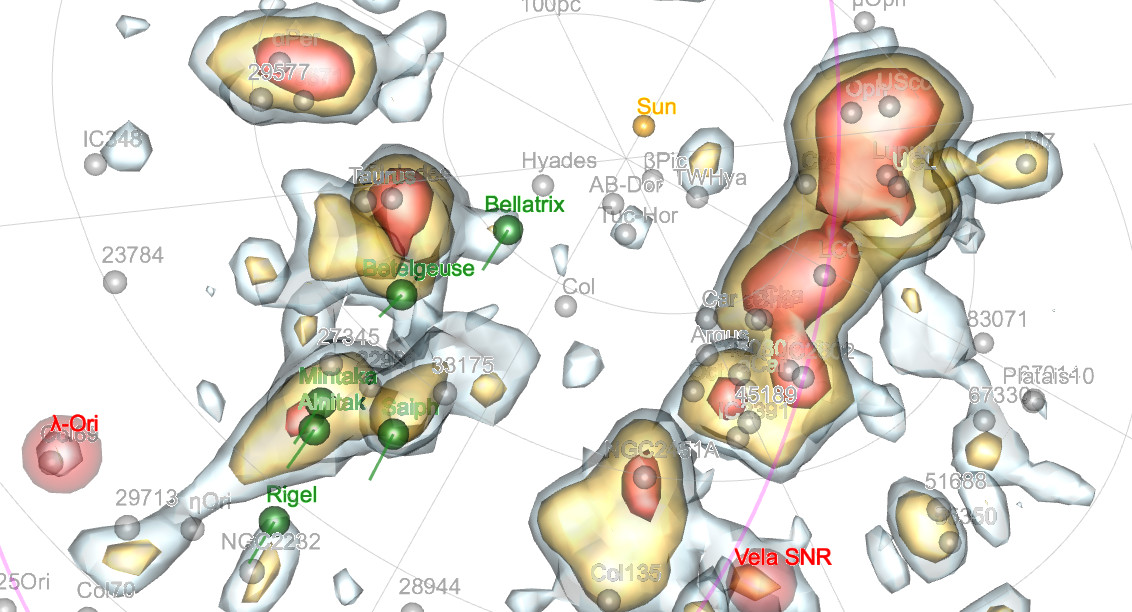

The team found that the solar neighbourhood is dominated by three huge stream-like galactic structures made up of dense clusters and loose associations of young, blue, O and B type stars. These contain several tens of O and B type stars, most of the local well-known clusters, and some previously unreported stellar groups. The first structure runs from the constellation Scorpius to the constellation Canis Majoris covering more than 1100 light-years and at least 65 million years of star formation history. The second, located in the constellation Vela, covers at least 500 light-years and 30 million years of history. Although all three of the newly discovered streams have a story to tell, it is the third structure, located in the constellation Orion, that is perhaps the most significant due to its mystery-solving qualities.

The origin of the blue supergiants that define the body and belt of the Orion constellation has long been a mystery. The five giant O and B type stars are located between around 250 and 800 light-years from Earth and as a result it was assumed that their origin was not, despite their name, in the prolific Orion Nebula star-forming region, which lies around 1300 light-years from Earth. However, the discovery of the Orion stream offers a simple solution. It implies that these relatively distant populations are in fact linked as part of a large galactic structure, which spans more than 1000 light-years and at least 25 million years of star formation history.

The origin of the body and belt are not the only answers this study might hold for the birth of the Hunter.

“One exciting find from this study relates to Betelgeuse, the red giant in the arm of Orion,” remarks Bouy. “The origin of this star has always been shrouded in mystery but through this study we have uncovered a new loosely organised group — or OB association — named Taurion which we believe to be Betelgeuse’s birthplace and to contain its sibling stars.”

“The Gould Belt is the perfect example of how 2-D projections can deceive astronomers,” argues Alves. “Our results imply that it is just a projection effect produced by the Sun’s position between two of the streams of stars, rather than representing the architecture of the solar neighbourhood itself.”

The results published in this study include caveats and possible sources of error in part due to the extinction in the Hipparcos data, in other words the amount of light that was absorbed and scattered by dust on its way to the telescope, compromising the quality of the data. The study is also biased towards young stars, due to its focus on O and B type stars, and dense stellar groups. Despite this, the results show that our current models of the solar neighbourhood are not sufficient to uncover the true structure of how its stellar inhabitants are distributed or trace the history of their formation and evolution, there is significantly more to learn about our local environment.

“These results show just what 3-D visualisation can deliver, and how much further it can take us,” explains Jos de Bruijne, ESA’s Gaia system scientist, also acting as ESA liaison scientist for the Hipparcos mission. “It provides an even stronger case for focussing on the local neighbourhood and, in particular, for doing so in three dimensions. This study really raises the expectations for what the Gaia mission will produce.”

Gaia was launched in 2013 with the aim of unveiling the origin and evolution of our Galaxy. It will provide measurements of the positions and velocities with respect to Earth of up to one billion stars in our Galaxy and Local Group with unprecedented accuracy and sensitivity. The three-dimensional map produced by Gaia will far outdo any current or foreseen maps of the stars in the Milky Way. It will include non-O and-B type stars and be able to identify clusters and groups not dense enough to register in the Hipparcos map.

The success of the Hipparcos study in highlighting the benefits of visualising 25-year-old data using modern visualisation methods emphasises the potential of stellar mapping in 3-D and Gaia will provide the data needed to peer further into the origin, evolution and structure of our Galaxy.

An interactive tool showing the Hipparcos data represented in three dimensions is available online.