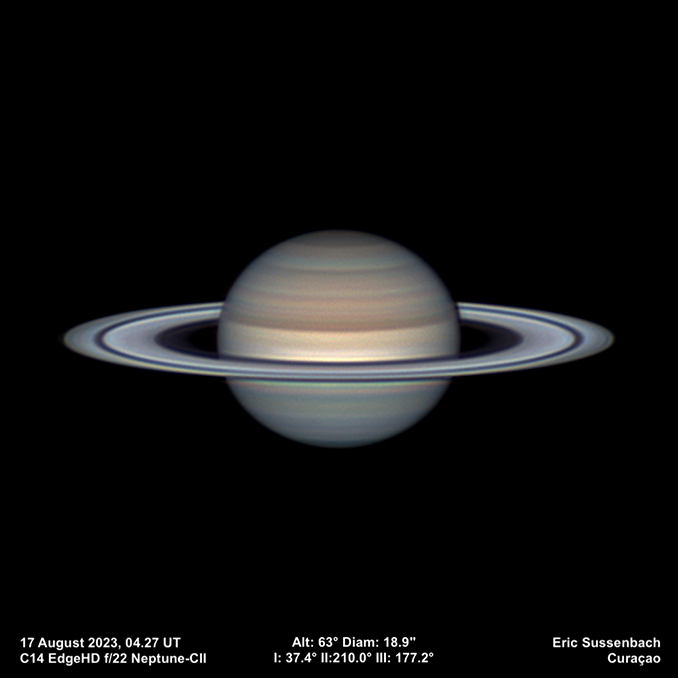

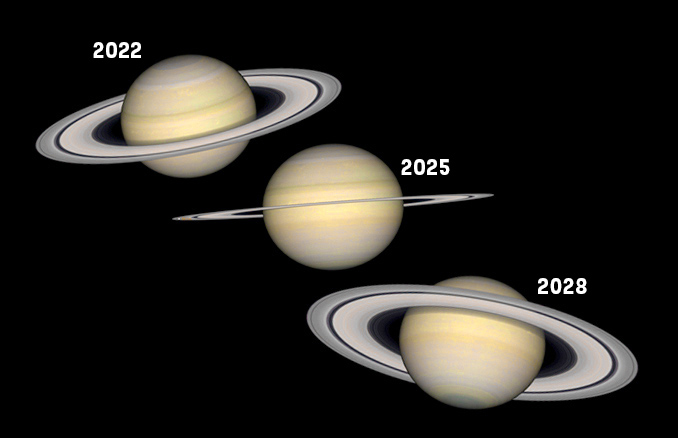

The magnificent ringed planet Saturn is arguably the most popular planet, but undoubtably it’s the most stunning of all through the eyepiece. Saturn is special for its fantastic system of rings that are easy to see through even a small telescope. Unfortunately, the rings are ‘closing up’ from our perspective, on their way to an edge-on presentation in 2025. Despite this, the rings retain plenty of their glory and are well seen (see below).

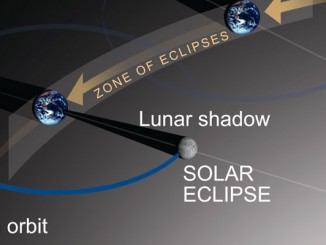

On Sunday, 27 August Saturn reaches it absolute best for the year, when it lies opposite the Sun in the sky, with Earth lined up between. This alignment is what astronomers term ‘opposition’, and its when Saturn, or indeed any superior planet (those which orbit the Sun at a greater distance than that of the Earth) offer optimum visibility.

Saturn’s year-on-year altitude in the northern sky is on an upwards curve since a nadir for UK observers at its oppositions of 2018 and 2019, when in Saturn languished in Sagittarius. Nevertheless, Saturn remains located south of the celestial equator (Saturn doesn’t cross into the northern sky until 2026) its declination of 20.6° south placing it among the stars of Aquarius.

Saturn shines at magnitude +0.4, an opposition brightness that’s at least nearly half a magnitude fainter than when the rings are fully ‘open’. However, Saturn dominates this part of the sky with its brightness and, together with its signature yellowish, or creamy hue, it’s unmistakable.

At opposition on 27 August, Saturn rises at 8pm BST and culminates shortly after 1am at an elevation of around 28° from the south of England. It can be observed at an altitude higher than 20° from about 10.40pm to 3.30am. From Scotland, Saturn culminates nearly 23° high at 1.18am BST.

Saturn’s stunning rings

The rings are tilted by 9°, though owing to changing viewing circumstances the rings steady year-on-year closure was arrested in June (7.2°). Since they have actually been opening out again and will reach a maximum tilt of 10.4° in early November, after which they begin to close up once more.

Over intervals of 13.75 and 15.75 years, alternately, the Earth passes through the plane of the rings and at such times when the rings are visible from Earth, they are presented very close to or precisely edge-on to our line of sight. The last time a so-called ring plane crossing occurred was in 2009, and the next occurs in March 2025. The rings were last fully open (tilted by around 26 to 27 degrees towards us) not in 2017.

From Earth, three distinct, major rings can be seen encircling Saturn’s equator. The outer ring, Ring A, is divided about 20 per cent of the way in from its outer edge by the elusive 325-kilometre-wide Encke Gap, or Division. The middle ring, Ring B, is the broadest (width 25,500 km) and brightest ring and is separated from Ring A by the famous 3,000-kilometre-wide Cassini Division.

Inside Ring B is the dusky and very faint Ring C, or Crêpe Ring. The rings are composed overwhelmingly of water-ice with some rocky content, the individual particles ranging from micron- to metre-size.

A small- to medium- sized telescope in the 80–150mm (3- to 6-inch) class will show Ring A and Ring B, though you’ll probably need a 250mm (ten-inch) telescope to see the Cassini Division.

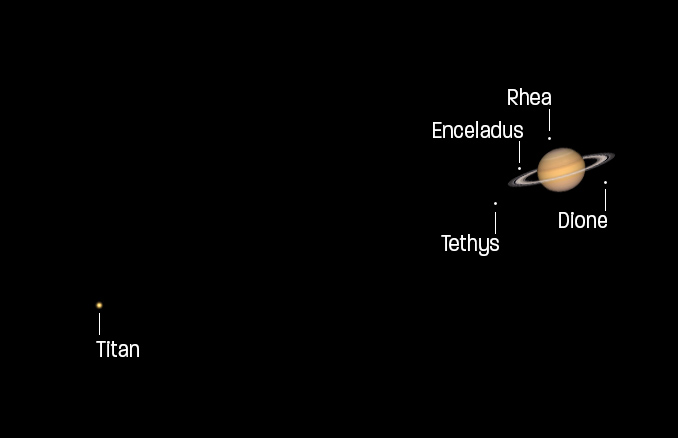

Track down Titan, Saturn’s giant Moon

The giant moon Titan is by far Saturn’s dominant satellite and one of the very special objects in the Solar System, memorably visited in 2004 by the Huygens probe released from the Cassini spacecraft. It is only two per cent smaller than Jupiter’s giant, Ganymede, its 5,150 kilometre (3,200 miles) diameter making it larger than the planet Mercury and 50 per cent larger than our Moon.

Titan orbits Saturn once every 15.94 days in a tidally locked synchronous rotation. It shines at magnitude +8.4, bright enough to be seen through steadily-held or mounted 10 x 50 binoculars when Saturn is more favourably placed. At this opposition though, a small telescope might be a better bet to locate it close to its maximum eastern elongation from Saturn, some 3 arcminutes. It’s large enough to show a diminutive disc through very large telescopes, subtending an angle of 0.8 arcseconds.

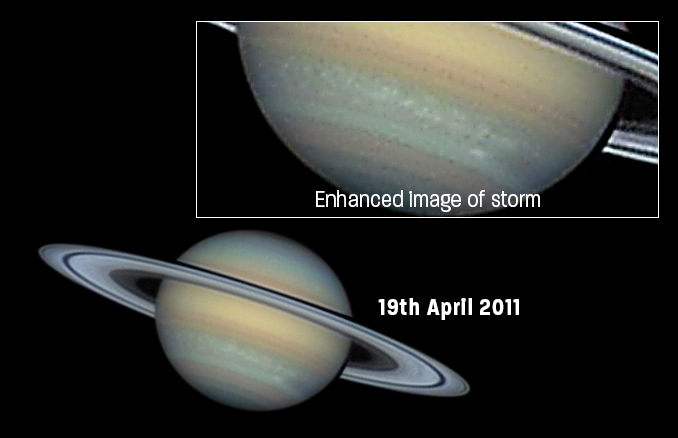

Subtle banding on Saturn’s globe

Like Jupiter, Saturn displays dark belts and brighter zones. However, it lies twice as far away from the Sun as its fellow gas giant and receives much less energy to enliven its atmosphere, resulting in a much more subtle effect.

Today’s startlingly good amateur images reveal their true extent, but all that’s likely to be on currently on show visually is a brighter equatorial belt, an equatorial belt and a perhaps a dark polar hood.