There are so many bright galaxies to choose from in springtime, but one you definitely shouldn’t miss is the marvellous ‘Black Eye Galaxy’, or Messier 64. It’s a real crowd-pleaser lying among the stars of Coma Berenices that can be located in a finderscope or 10 x 50 binoculars.

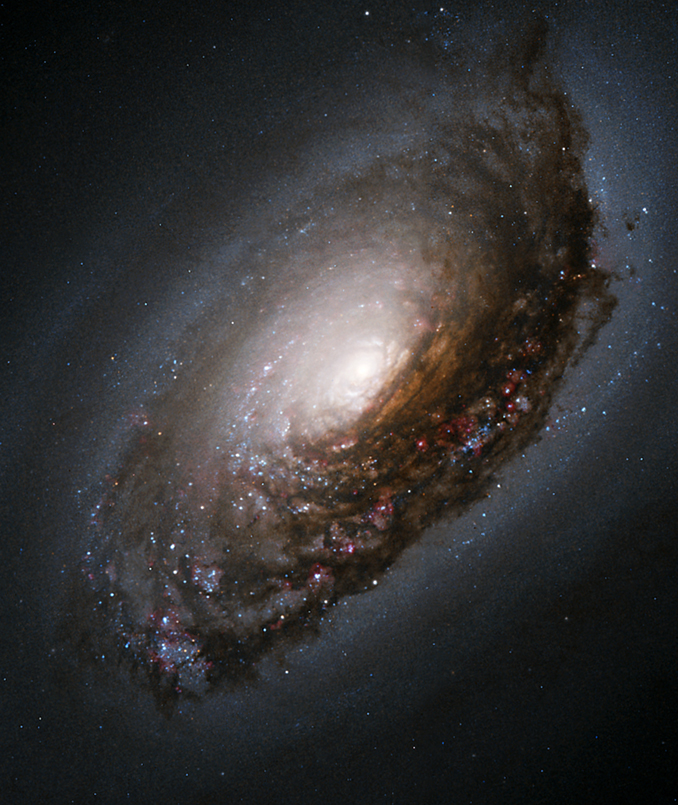

M64’s very apt nickname is on account of the extraordinary feature of a dark, obscuring band of gas and dust on the north side of its nucleus, a special sight that doesn’t require a huge telescope to see and yields fine images through moderate-aperture telescopes.

How to observe

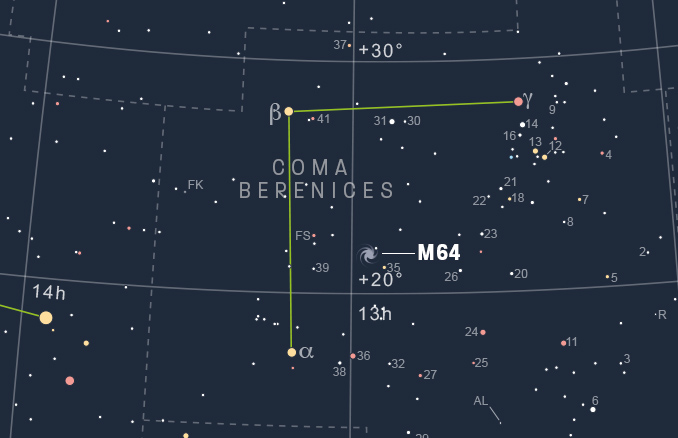

Messier 64 (NGC 4826) lies almost right in the middle of Coma Berenices, just under a degree north-west of magnitude +4.9 35 Comae Berenices. This places it about 12 degrees north of the main concentration of galaxies, most of which belong to the incredible Virgo Cluster of galaxies, which populate the area around the boundary between Virgo and Coma. M64 lies about 18 million light years distant, which places it about three times closer to our Solar System than the Virgo Cluster.

At mid-May from London M64 has just culminated (at its highest altitude in the sky) by the time darkness falls and remains well placed for the rest of the relatively short night.

M64 shines brightly, for a spiral galaxy at least, at magnitude +8.5, and, despite being physically quite a small galaxy (diameter of 56,000 light years), it appears relatively large to us, with an apparent diameter of 9.2 x 4.6 arcminutes. It has been formally classified as SA(rs)ab under the de Vaucouleurs morphological scheme, indicating that it is an unbarred spiral with somewhat tightly wound, smooth spiral arms and a large, bright central bulge.

The amazing ‘Black Eye’ at M64’s core is formed from absorbing dust clouds punctuated by a large number of star-forming H-II regions. In order to give yourself the best chance of observing it wait for M64 to reach close to culmination on a moonless night and transparent night. A four-inch (100mm) telescope operating at moderate to high magnification should be provide sufficient light grasp and resolution for it to be observed, but you’d do better with a six- or eight-inch (150–200mm) ‘scope.

Messier 64’s discovery is credited to the English astronomer Edward Pigott, who spied a faint smudge in his one-metre focal length refractor on 23 March 1779. Twelve days later Johan Elert Bode, Messier’s fierce competitor, made an independent discovery. Charles Messier found it on 1 March 1780 and John Herschel observed it 50 years later, being the first to comment on the ‘Black Eye’