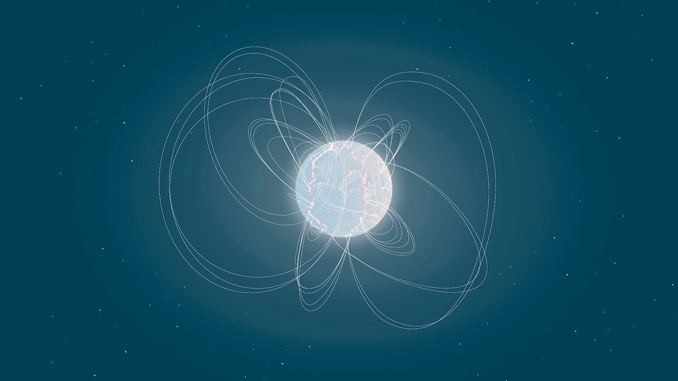

Astronomers have found what appears to be the youngest neutron star yet discovered, a compact, fast-spinning pulsar born in a supernova blast just 240 years ago that boasts a magnetic field 70 quadrillion times stronger than Earth’s. That makes it one of just 31 magnetars discovered to date in a population of more than 3,000 known neutron stars.

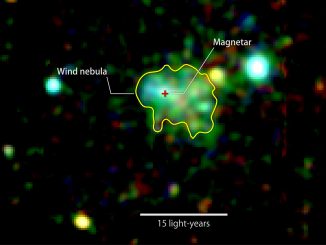

Known as Swift J1818.0−1607, the magnetar is about 15,000 light years from Earth in the constellation Sagittarius. It completes one rotation every 1.36 seconds and crams twice the mass of the Sun into a body just 25 kilometres (15 miles) across.

“Spotting something so young, just after it formed in the Universe, is extremely exciting,” said Paolo Esposito of the University School for Advanced Studies IUSS Pavia, Italy, and lead author of a paper in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“People on Earth would have been able to see the supernova explosion that formed this baby magnetar around 240 years ago, right in the middle of the American and French revolutions.”

Neutron stars are formed when the cores of massive stars run out of nuclear fuel and are no longer able to support themselves against the inward crush of gravity. As the core collapses to extreme densities, the star’s outer layers are blown away, seeding space with the heavy elements and other raw materials needed for new stars.

Spinning neutron stars are known as pulsars and a fraction of the pulsars discovered to date boast extremely powerful magnetic fields. They are known as magnetars. Swift J1818.0−1607’s magnetic field is up to 1,000 times stronger than that of a typical neutron star and about 100 million times stronger than the most powerful magnets made by humans.

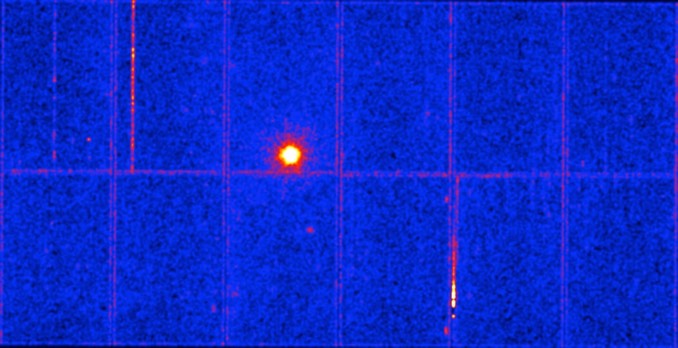

Swift J1818.0−1607 was first spotted, as the name suggests, by NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory on 12 March when a powerful burst of X-rays was seen. Researchers with the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton observatory and NASA’s NuSTAR telescope, along with Sardinia Radio Telescope in Italy, then carried out extensive follow-up observations.

“Magnetars are fascinating objects, and this baby one appears to be especially intriguing given its extreme characteristics,” said Nanda Rea of the Institute of Space Sciences in Barcelona, Spain, and principal investigator of the observations.

“The fact that it can be seen in both radio waves and X-rays offers an important clue in an ongoing scientific debate on the nature of a specific type of stellar remnant: pulsars.”

Magnetars are generally thought to be rare and distinct from other pulsars that show up primarily in radio emissions. But they may be much more common.

“The fact that a magnetar formed just recently indicates that this idea is well-founded,” said co-author Alice Borghese, based at the Institute of Space Sciences in Barcelona.

“Astronomers have also discovered many magnetars in the past decade, doubling the known population,” she added. “It’s likely that magnetars are just good at flying under the radar when they’re dormant, and are only discovered when they ‘wake up’ – as demonstrated by this baby magnetar, which was far less luminous before the outburst that led to its discovery.”