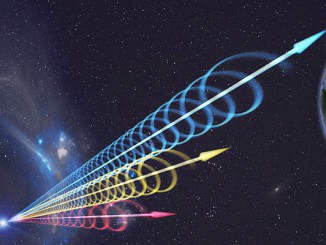

When fast radio bursts, or FRBs, were first detected in 2001, astronomers had never seen anything like them before. Since then, astronomers have found a couple of dozen FRBs, but they still don’t know what causes these rapid and powerful bursts of radio emission.

For the first time, two astronomers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) have estimated how many FRBs should occur over the entire observable universe. Their work indicates that at least one FRB is going off somewhere every second.

“If we are right about such a high rate of FRBs happening at any given time, you can imagine the sky is filled with flashes like paparazzi taking photos of a celebrity,” said Anastasia Fialkov of the CfA, who led the study. “Instead of the light we can see with our eyes, these flashes come in radio waves.”

To make their estimate, Fialkov and co-author Avi Loeb assumed that FRB 121102, a fast radio burst located in a galaxy about 3 billion light-years away, is representative of all FRBs. Because this FRB has produced repeated bursts since its discovery in 2002, astronomers have been able to study it in much more detail than other FRBs. Using that information, they projected how many FRBs would exist across the entire sky.

“In the time it takes you to drink a cup of coffee, hundreds of FRBs may have gone off somewhere in the universe,” said Avi Loeb. “If we can study even a fraction of those well enough, we should be able to unravel their origin.”

While their exact nature is still unknown, most scientists think FRBs originate in galaxies billions of light-years away. One leading idea is that FRBs are the byproducts of young, rapidly spinning neutron stars with extraordinarily strong magnetic fields.

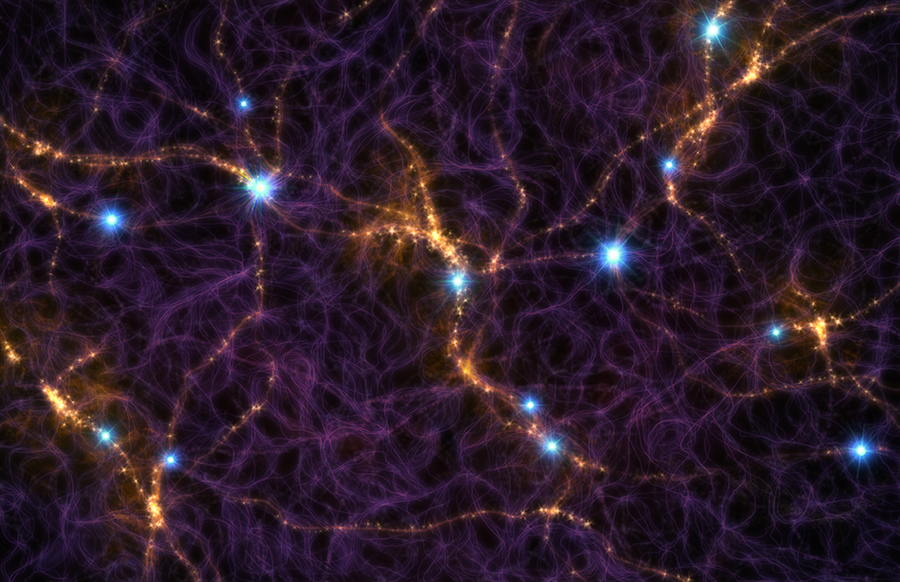

Fialkov and Loeb point out that FRBs can be used to study the structure and evolution of the universe whether or not their origin is fully understood. A large population of faraway FRBs could act as probes of material across gigantic distances. This intervening material blurs the signal from the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the leftover radiation from the Big Bang. A careful study of this intervening material should give an improved understanding of basic cosmic constituents, such as the relative amounts of ordinary matter, dark matter and dark energy, which affect how rapidly the universe is expanding.

FRBs can also be used to trace what broke down the “fog” of hydrogen atoms that pervaded the early universe into free electrons and protons, when temperatures cooled down after the Big Bang. It is generally thought that ultraviolet (UV) light from the first stars traveled outwards to ionize the hydrogen gas, clearing the fog and allowing this UV light to escape. Studying very distant FRBs will allow scientists to study where, when and how this process of “reionization” occurred.

“FRBs are like incredibly powerful flashlights that we think can penetrate this fog and be seen over vast distances,” said Fialkov. “This could allow us to study the ‘dawn’ of the universe in a new way.”

The authors also examined how successful new radio telescopes — both those already in operation and those planned for the future — may be at discovering large numbers of FRBs. For example, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) currently being developed will be a powerful instrument for detecting FRBs. The new study suggests that over the whole sky the SKA may be able to detect more than one FRB per minute that originates from the time when reionization occurred.

The Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME), that recently began operating, will also be a powerful machine for detecting FRBs, although its ability to detect the bursts will depend on their spectrum, i.e., how the intensity of the radio waves depends on wavelength. If the spectrum of FRB 121102 is typical then CHIME may struggle to detect FRBs. However, for different types of spectra CHIME will succeed.