By observing its transit precisely using the next generation of telescopes, such as the Thirty Metre Telescope (TMT), scientists expect to be able to search the atmosphere of the planet for molecules related to life, such as oxygen.

With only the previous space telescope observations, however, researchers can’t calculate the orbital period of the planet precisely, which makes predicting the exact times of future transits more difficult. This research group has succeeded in measuring the orbital period of the planet with a high precision of about 18 seconds. This greatly improved the forecast accuracy for future transit times. So now researchers will know exactly when to watch for the transits using the next generation of telescopes. This research result is an important step towards the search for extraterrestrial life in the future.

K2-3d

K2-3d is an extrasolar planet 147 light-years away that was discovered by NASA’s Kepler K2 mission. K2-3d’s size is 1.5 times that of the Earth. The planet orbits its host star — also known as EPIC 201367065, hosting two other super-Earth exoplanets, K2-3b and c — which is half the size of the Sun, with a period of about 45 days. Compared to the Earth, the planet orbits close to its host star (about ⅕ of the Earth-Sun distance). But, because the temperature of the host star is lower than that of the Sun, calculations show that this is the right distance for the planet to have a relatively warm climate like the Earth’s. There is a possibility that liquid water could exist on the surface of the planet, raising the tantalising possibility of extraterrestrial life.

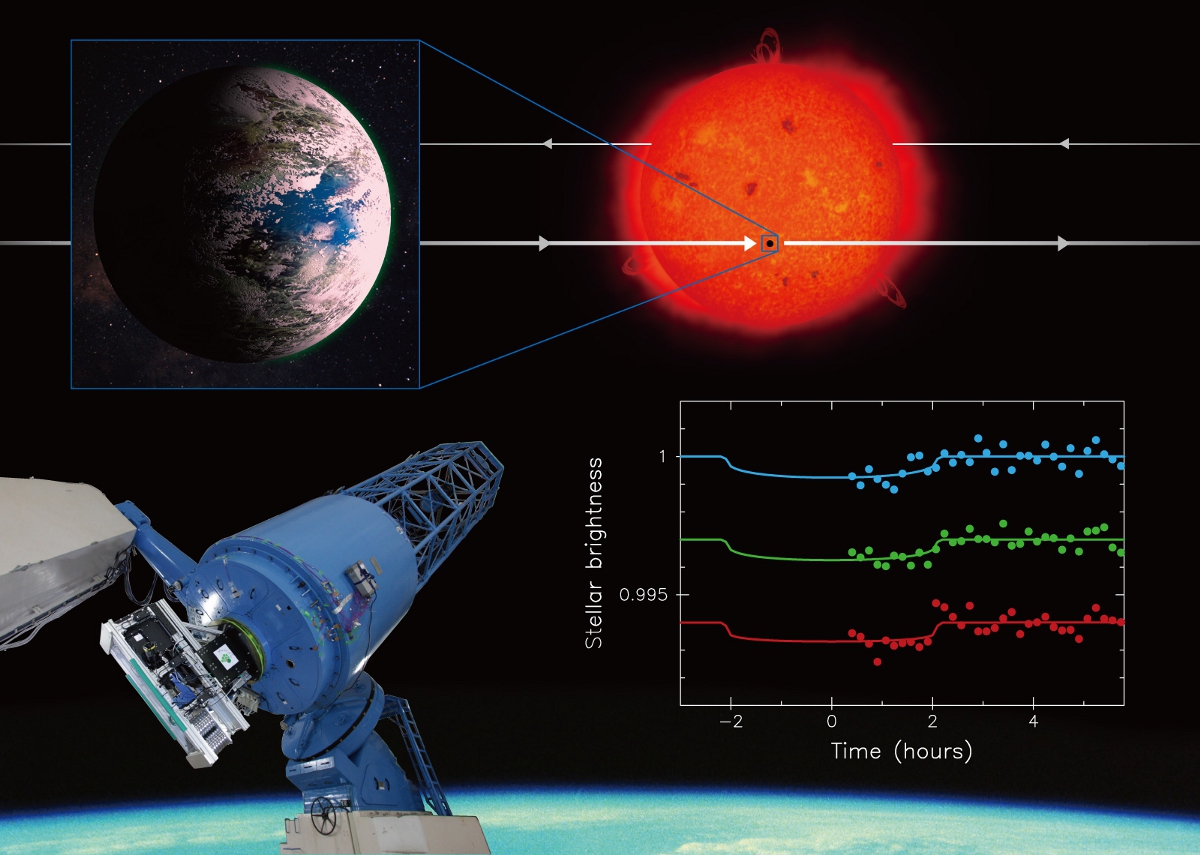

About 30 potentially habitable planets that also have transiting orbits were discovered by NASA’s Kepler mission, but most of these planets orbit fainter, more distant stars. Because it is closer to Earth and its host star is brighter, K2-3d is a more interesting candidate for detailed follow-up studies. The brightness decrease of the host star caused by the transit of K2-3d is small, only 0.07 percent. However, it is expected that the next generation of large telescopes will be able to measure how this brightness decrease varies with wavelength, enabling investigations of the composition of the planet’s atmosphere. If extraterrestrial life exists on K2-3d, scientists hope to be able to detect molecules related to it, such as oxygen, in the atmosphere.

MuSCAT observations and transit ephemeris improvements

The orbital period of K2-3d is about 45 days. Since the K2 mission’s survey period is only 80 days for each area of sky, researchers could only measure two transits in the K2 data. This isn’t sufficient to measure the planet’s orbital period precisely, so when researchers attempt to predict the times of future transits, creating something called a “transit ephemeris,” but there are uncertainties in the predicted times. These uncertainties grow larger as they try to predict further into the future. Therefore, early additional transit observations and adjustments to the ephemeris were required before researchers lost track of the transit. Because of the importance of K2-3d, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope observed two transits soon after the planet’s discovery, bringing the total to four transit measurements. However, the addition of even a single transit measurement farther in the future can help to yield a significantly improved ephemeris.

Using the Okayama 188-centimetre Reflector Telescope and the latest observational instrument MuSCAT, the team observed a transit of K2-3d for the first time with a ground-based telescope. Though a 0.07 percent brightness decrease is near the limit of what can be observed with ground-based telescopes, MuSCAT’s ability to observe three wavelength bands simultaneously enhanced its ability to detect the transit. By reanalysing the data from K2 and Spitzer in combination with this new observation, researchers have greatly improved the precision of the ephemeris, determining the orbital period of the planet to within about 18 seconds (1/30 of the original uncertainty). This improved transit ephemeris ensures that when the next generation of large telescopes come online, they will know exactly when to watch for transits. Thus these research results help pave the way for future extraterrestrial life surveys.

Future work

NASA’s K2 mission will continue until at least February 2018 and is expected to discover more potentially habitable planets like K2-3d. Furthermore, K2’s successor, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), will be launched in December 2017. TESS will survey the whole sky for two years and is expected to detect hundreds of small planets like K2-3d near our solar system. To characterise a ‘second Earth’ using the next generation of large telescopes, it will be important to measure the ephemerides and characteristics of planets with additional transit observations using medium sized ground-based telescopes. The team will continue using MuSCAT for research related to the future search for extraterrestrial life.

The researchers results were just published in The Astronomical Journal.