Ground teams are buying more time to study two sluggish valves inside the Juno spacecraft’s fuel pressurisation system and postponing a major engine burn that was scheduled for this week to reshape the probe’s orbit around Jupiter.

The rocket burn was slated for 19 October as the Juno spacecraft dived toward Jupiter for its second close approach, or perijove, since arriving in Jupiter’s orbit 4 July. The manoeuvre is necessary to place Juno into its final science orbit, an orbit selected to maximize the $1 billion mission’s scientific bounty and minimize exposure to harmful radiation that could fry the craft’s electronics.

But ground controllers encountered an issue with two helium check valves inside Juno’s fuel pressurisation system last week, according to a NASA statement.

“Telemetry indicates that two helium check valves that play an important role in the firing of the spacecraft’s main engine did not operate as expected during a command sequence that was initiated yesterday,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “The valves should have opened in a few seconds, but it took several minutes. We need to better understand this issue before moving forward with a burn of the main engine.”

After consulting with NASA Headquarters and Lockheed Martin, the manufacturer of the Juno spacecraft, the Juno team elected to delay the rocket firing, known as the period reduction manoeuvre, by at least one orbit to allow engineers to evaluate the valves, the space agency said in a press release issued late Friday.

The period reduction manoeuvre is planned to be final burn of Juno’s Leros 1b main engine, which successfully fired 4 July for 35 minutes to steer Juno into an initial orbit around Jupiter. Manoeuvres needed later in Juno’s mission — due to end in February 2018 — can be done using the orbiter’s smaller rocket thrusters.

The Leros 1b engine burns a mixture of hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide to produce about 145 pounds of thrust. Juno carries a supply of gaseous helium to pressurise the propellant tanks and plumbing before an engine burn.

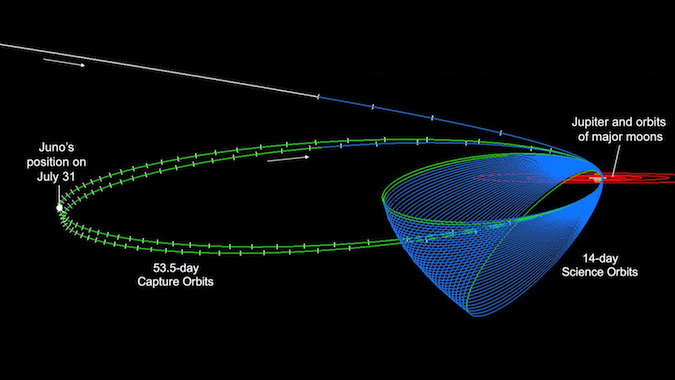

Juno slid into a looping orbit around Jupiter after the make-or-break arrival burn. In its current orbit, which takes the spacecraft as far as 8.1 million kilometres from Jupiter, Juno completes one lap around the giant planet every 53 days.

The period reduction manoeuvre is designed to do exactly what its name implies: reduce the period of time for Juno to make one orbit from 53 days to 14 days.

The rocket burn will slow down Juno’s speed around Jupiter, dropping the highest point of each orbit closer to the planet. The laws of orbital mechanics require the burn to happen when Juno is close to the planet, at perijove just a few thousand miles above Jupiter’s cloud tops.

The next time Juno will be that close after next week is 11 December, so managers have penciled in that date for the period reduction manoeuvre.

Scientists say Juno can still collect the same type of science data as expected regardless of whether its orbit is lowered or not, but the longer path around Jupiter means fewer opportunities to capture the measurements and imagery researchers are eager to see.

Ground controllers planned to switch off most of Juno’s science instruments for the Oct. 19 flyby to allow the spacecraft to focus on the engine burn. With the change of plans, all nine of Juno’s instruments, comprising 29 individual sensors, will be activated for the close approach next week.

“It is important to note that the orbital period does not affect the quality of the science that takes place during one of Juno’s close flybys of Jupiter,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “The mission is very flexible that way. The data we collected during our first flyby on 27 August was a revelation, and I fully anticipate a similar result from Juno’s 19 October flyby.”

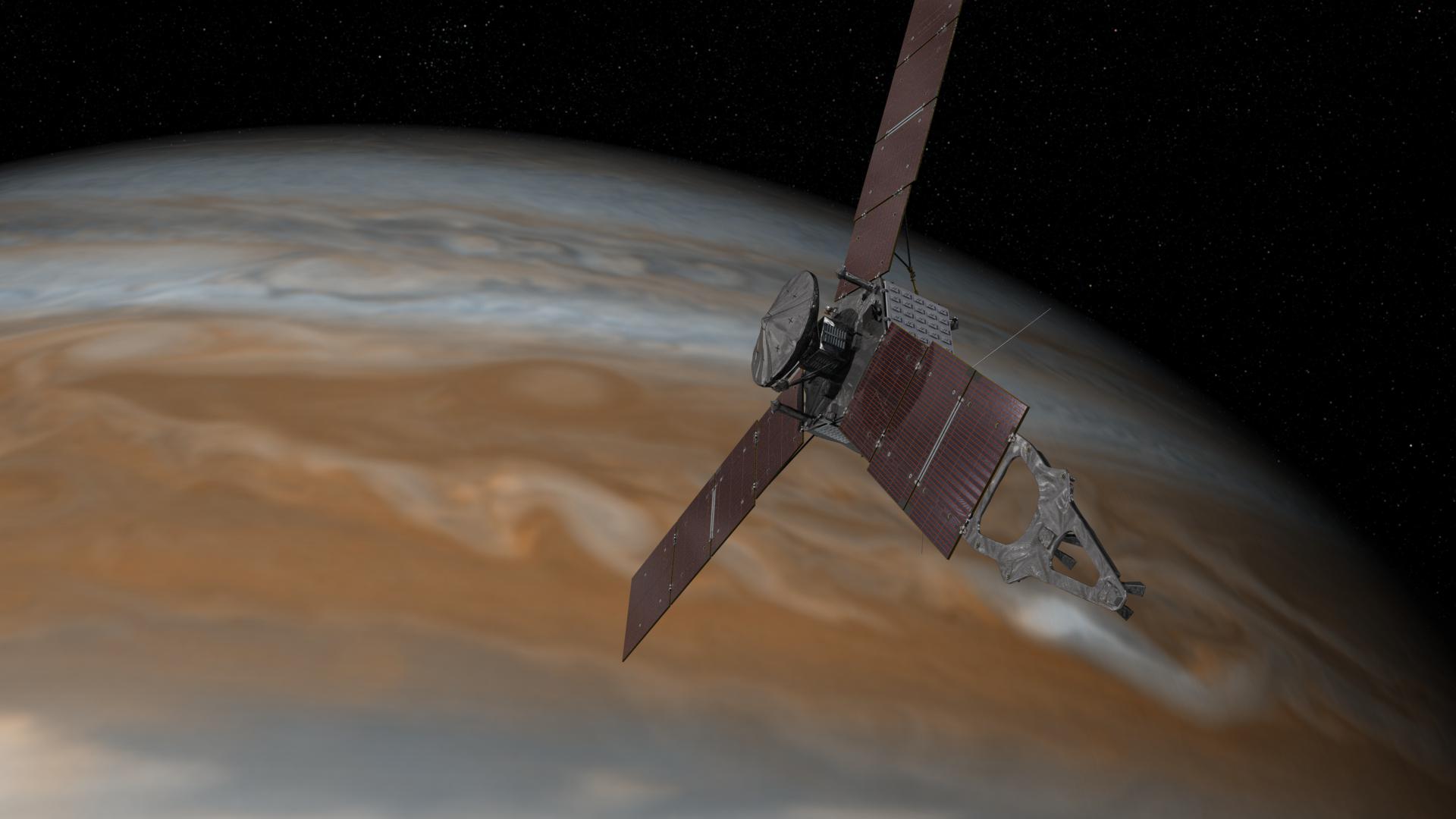

Juno’s objective is to unravel the mysteries of Jupiter’s interior, learn how the planet’s intense magnetic field is generated and how it traps charged particles in toxic radiation belts, and probe the structure beneath Jupiter’s turbulent clouds to find out what drives the gaseous world’s storms and whether it has a solid core.

Mission planners originally intended to put Juno into a preliminary 107-day orbit around Jupiter after arrival, then drive the probe into the shorter 14-day orbit 19 October. But officials decided after Juno’s launch in August 2011 to change the plan, and instead have Juno go into a 53-day orbit, where it would fly around the planet two times before starting the mission’s regular science campaign.

Managers had contingency plans to hold off on the period reduction manoeuvre in case Juno encountered technical problems, such as the current issue with the propulsion system, or if there was more radiation in the spacecraft’s path than anticipated.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.