When and how to see Uranus

As seen from the centre of the British Isles, Uranus currently attains a maximum altitude of slightly more than 44 degrees above the southern horizon at 1:30am BST. By the end of October, when the clocks have gone back one hour, Uranus will be highest in the UK sky shortly before 11pm GMT.

Given the planet’s respectable altitude in the south at culmination and its current magnitude of +5.7, it’s entirely possible that the keen-eyed among you will be able to find Uranus with the unaided eye on moonless nights. Since first quarter Moon occurs on Sunday 9 October, moonlight will be a problem until around midnight in the British Isles on that date. Thereafter, the glare of the lunar orb will be troublesome until around 21 October when dark evening skies return.

To identify Uranus with the naked eye, one needs not only a moonless night when the planet is high above the horizon murk, but a location that is free from light pollution. Find a safe, rural location as far removed from streetlights as you can and allow your eyes at least 15 minutes to become fully adapted to the dark. If you have printed the greyscale versions of the finder charts above and below, study them under a dim red light so as to preserve your dark adaption.

For those of you with binoculars and the smallest of telescopes, however, moonlight presents no impediment to finding Uranus. The planet is obvious with the slightest optical aid, even when seen from an urban location with the Moon in the sky. That said, the full Moon of the night 15-16 October passes just 3.3 degrees (or two-thirds of a 10×50 binocular field) south of Uranus, offering a very convenient (if bright) means of locating the planet — though don’t confuse Uranus with magnitude +4.8 mu (μ) Piscium (see below).

Star-hopping to Uranus by naked-eye and binocular

Start your search by identifying the Square of Pegasus — an asterism that is highest in the southern sky at 11pm BST mid-October — and locate its lower-left corner, a magnitude +2.8 star known as gamma (γ) Pegasi, or Algenib. Next, move 12 degrees, or two-and-a-half 10×50 binocular fields, to the lower-left of Algenib until you reach magnitude +4.4 star delta (δ) Piscium — you are now on the curved east-west line of stars that forms the southern fish of the constellation Pisces.

Just 3.5 degrees (or two-thirds of a 10×50 binocular field) to the left of delta (δ) Piscium lies fractionally fainter star epsilon (ε) Piscium. And 2.7 degrees (half a binocular field) to the left of epsilon brings you to zeta (ζ) Piscium, an attractive double star for small telescopes with a 23-arcsecond separation. We are now on the right-hand edge of the brown rectangle encompassing Uranus on the wide-field chart above, a region seen in far greater detail below.

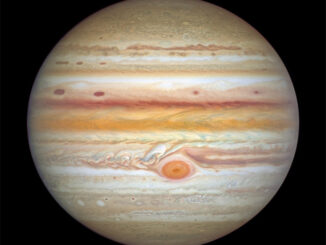

If Uranus seems star-like in binoculars, then the view doesn’t improve dramatically in small telescopes. However, in medium-sized amateur instruments the cyan colour of Uranus’ tiny disc can be seen. Despite the planet’s size — it has a diameter four times that of the Earth, making it the third largest planet in the solar system — its great distance of 18.95 astronomical units, or 1,762 million miles (2,835 million kilometres) from Earth, means that its disc appears just 3.7 arcseconds across. To put that in perspective, you need a magnification of 500x to enlarge Uranus to the same size as the full Moon appears to the unaided eye.

The large outer Uranian moons Titania (magnitude +13.7, orbital period 8.7 days) and Oberon (magnitude +13.9, orbital period 13.5 days) may be detected in large amateur telescopes when at greatest elongation from their parent planet. Oberon lies 42 arcseconds north of Uranus on 12 October and a similar distance south of the planet on 19 October. Titania lies 32 arcseconds north of Uranus on 16 October and a similar distance south of its parent planet on 20 October.

Inside the magazine

For a comprehensive guide to observing all that is happening in the current month’s sky, tailored to Western Europe, North America and Australasia, obtain a copy of the October 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.