In a paper to be published today in the journal Science Advances, lead author Karen Meech of the University of Hawai`i’s Institute for Astronomy and her colleagues conclude that C/2014 S3 (PANSTARRS) formed in the inner solar system at the same time as the Earth itself, but was ejected at a very early stage.

Their observations indicate that it is an ancient rocky body, rather than a contemporary asteroid that strayed out. As such, it is one of the potential building blocks of the rocky planets, such as the Earth, that was expelled from the inner solar system and preserved in the deep freeze of the Oort Cloud for billions of years.

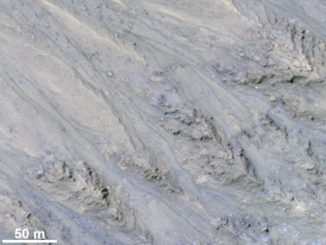

C/2014 S3 (PANSTARRS) was originally identified by the Pan-STARRS1 telescope as a weakly active comet a little over twice as far from the Sun as the Earth. Its current long orbital period (around 860 years) suggests that its source is in the Oort Cloud, and it was nudged comparatively recently into an orbit that brings it closer to the Sun.

The team immediately noticed that C/2014 S3 (PANSTARRS) was unusual, as it does not have the characteristic tail that most long-period comets have when they approach so close to the Sun. As a result, it has been dubbed a Manx comet, after the tailless cat. Within weeks of its discovery, the team obtained spectra of the very faint object with ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile.

The authors conclude that this object is probably made of fresh inner solar system material that has been stored in the Oort Cloud and is now making its way back into the inner solar system.

A number of theoretical models are able to reproduce much of the structure we see in the solar system. An important difference between these models is what they predict about the objects that make up the Oort Cloud. Different models predict significantly different ratios of icy to rocky objects. This first discovery of a rocky object from the Oort Cloud is therefore an important test of the different predictions of the models. The authors estimate that observations of 50–100 of these Manx comets are needed to distinguish between the current models, opening up another rich vein in the study of the origins of the solar system.

Co-author Olivier Hainaut (ESO, Garching, Germany), concludes: “We’ve found the first rocky comet, and we are looking for others. Depending how many we find, we will know whether the giant planets danced across the solar system when they were young, or if they grew up quietly without moving much.”