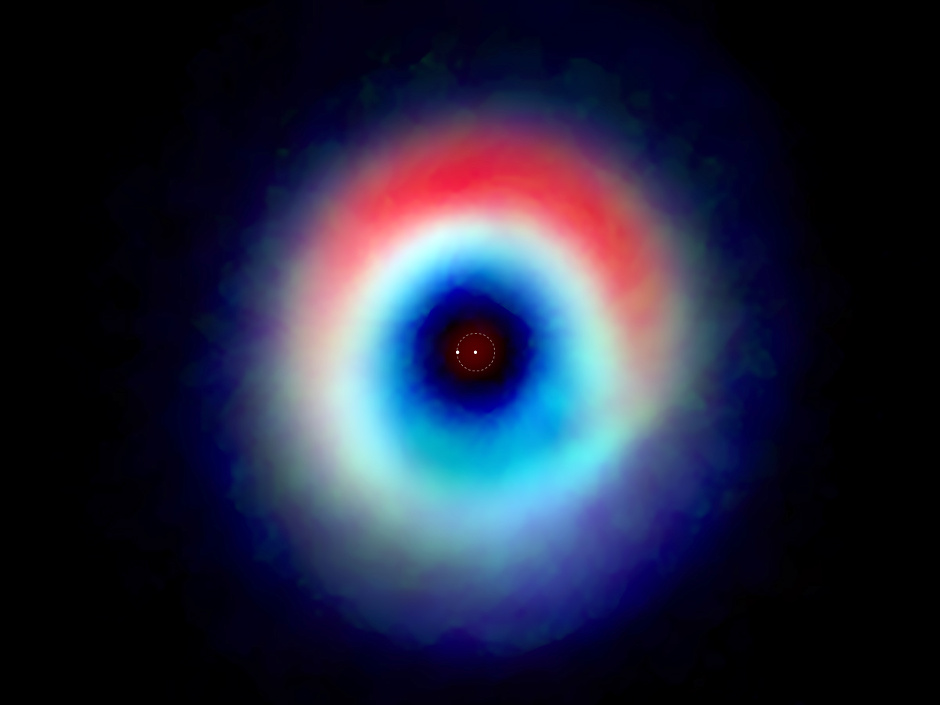

To better understand how such systems form and evolve, astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) took a new, detailed look at the planet-forming disc around HD 142527, a binary star about 450 light-years from Earth in a cluster of young stars known as the Scorpius-Centaurus Association.

The HD 142527 system includes a main star a little more than twice the mass of our Sun and a smaller companion star only about a third the mass of our Sun. They are separated by approximately one billion miles: a little more than the distance from the Sun to Saturn. Previous ALMA studies of this system revealed surprising details about the structure of the system’s inner and outer discs.

“This binary system has long been known to harbour a planet-forming corona of dust and gas,” said Andrea Isella, an astronomer at Rice University in Houston, Texas. “The new ALMA images reveal previously unseen details about the physical processes that regulate the formation of planets around this and perhaps many other binary systems.”

Planets form out of the expansive discs of dust and gas that surround young stars. Small dust grains and pockets of gas come together under gravity, forming larger and larger agglomerations and eventually asteroids and planets. The fine points of this process are not well understood, however. By studying a wide range of protoplanetary discs with ALMA, astronomers hope to better understand the conditions that set the stage for planet formation across the universe.

This crescent-shaped dust cloud may be the result of gravitational forces unique to binary stars and may also be the key to the formation of planets, Isella speculates. Its lack of free-floating gases is likely the result of them freezing out and forming a thin layer of ice on the dust grains.

“The temperature is so low that the gas turns into ice and sticks to the grains,” Isella said. “This process is thought to increase the capacity for dust grains to stick together, making it a strong catalyst for the formation of planetesimals, and, down the line, of planets.”

“We’ve been studying protoplanetary discs for at least 20 years,” Isella said. “There are between a few hundred and a few thousand we can look at again with ALMA to find new and surprising details. That’s the beauty of ALMA. Every time you get new data, it’s like opening a present. You don’t know what’s inside.”