Although some of you will have already had a sneak preview of our updated online Almanac via links from recent Observing stories, we thought that it probably deserved a post of its own. Here, then, is our guide to exploring some of the new interactive Almanac’s enhanced features. We will explore more advanced themes in a subsequent post, but first a topical question concerning the visibility of all five bright naked-eye planets in the morning sky.

Example: Is Mercury currently best seen from Rome, Italy or Sydney, Australia?

Innermost planet Mercury attains a greatest elongation of 26 degrees west of the Sun at 1am GMT on Sunday, 7 February. This means that it is furthest from the Sun in the pre-dawn twilight and best placed for morning observation. So, is Mercury currently easier to see in the Northern or the Southern Hemisphere?

Observing circumstances from Rome, Italy

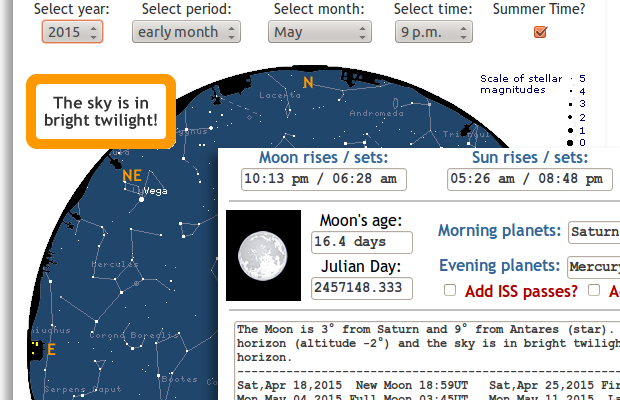

Launch the Almanac and first enter “2016/02/07” into the Date window (remember that the format must be year/month/day — “2016-2-7” or “2016/2/7” are equally acceptable — but don’t type the quotes) and the Universal Time/GMT “01:00” into the Time window (again without the quotes) and click the Calc button. The Almanac recomputes the new data. (Clicking Reset, incidentally, always restores the Almanac to the current date and time.) Next, go to the extreme upper right of the Almanac where you find the new twilight selector pull-down menu. Here you can determine the local time of Astronomical twilight (when the Sun is -18 degrees below the horizon), Nautical twilight (Sun -12 degrees below the horizon), Civil twilight (Sun -6 degrees below the horizon) or Bright planets last/first visible (Sun -9 degrees below the horizon) — we need the latter to determine when innermost planet Mercury is just fading into the bright twilight and highest in the morning sky.

Next, go to the extreme upper right of the Almanac where you find the new twilight selector pull-down menu. Here you can determine the local time of Astronomical twilight (when the Sun is -18 degrees below the horizon), Nautical twilight (Sun -12 degrees below the horizon), Civil twilight (Sun -6 degrees below the horizon) or Bright planets last/first visible (Sun -9 degrees below the horizon) — we need the latter to determine when innermost planet Mercury is just fading into the bright twilight and highest in the morning sky. Next, use the Country and City menus to select first “Italy” then “Rome” from the alphabetised pull-down lists. The Almanac will recompute and display localised data for Rome. Important note: the Almanac knows the time zones for all cities in its database, but currently requires you to know if the location observes Daylight Savings Time and to select/deselect it accordingly (www.thetimenow.com/ is a great resource if you are unsure). Since it’s currently Northern Hemisphere winter, we can be confident that Rome isn’t using DST in February, so the DST box should be unticked.

Next, use the Country and City menus to select first “Italy” then “Rome” from the alphabetised pull-down lists. The Almanac will recompute and display localised data for Rome. Important note: the Almanac knows the time zones for all cities in its database, but currently requires you to know if the location observes Daylight Savings Time and to select/deselect it accordingly (www.thetimenow.com/ is a great resource if you are unsure). Since it’s currently Northern Hemisphere winter, we can be confident that Rome isn’t using DST in February, so the DST box should be unticked. Next, we use the plus/minus hour and minute buttons to step forward/backward in time such that the Local Date & Time window displays the Rome time displayed in the Bright planets last visible window (i.e., 06:31 am). Now we can examine the observational data in the planetary data table.

Next, we use the plus/minus hour and minute buttons to step forward/backward in time such that the Local Date & Time window displays the Rome time displayed in the Bright planets last visible window (i.e., 06:31 am). Now we can examine the observational data in the planetary data table. We can see that on 7 February, Mercury rises at 05:56 am local time and at 06:31 am the Sun is indeed -9 degrees below Rome’s east-southeast horizon, rising at 07:17 am local time. At 06:31 am when the sky is not so bright as to render planet Mercury invisible in a clear sky, yet late enough for the innermost planet to reach its highest in twilight, we see that Mercury is +5 degrees high in the southeast.

We can see that on 7 February, Mercury rises at 05:56 am local time and at 06:31 am the Sun is indeed -9 degrees below Rome’s east-southeast horizon, rising at 07:17 am local time. At 06:31 am when the sky is not so bright as to render planet Mercury invisible in a clear sky, yet late enough for the innermost planet to reach its highest in twilight, we see that Mercury is +5 degrees high in the southeast.

Furthermore, the information box under the current Moon phase information states that the 28-day-old, 3 percent illuminated waning lunar crescent is 3 degrees above Rome’s east-southeast horizon and 8 degrees from magnitude zero Mercury, while the latter is 5 degrees from magnitude -4 Venus.

Observing circumstances from Sydney, Australia

Use the Country and City menus to select first “Australia” then “Sydney” from the alphabetised pull-down lists. The Almanac will recompute and display localised data for Sydney, NSW. The Almanac knows the time zone difference for Sydney, but currently requires you to know if the city observes Daylight Savings Time and to select/deselect it accordingly (remember to use www.timeanddate.com if you are unsure). Since it’s currently Southern Hemisphere winter, we can be confident that Sydney, NSW is using DST in February, so ensure that the DST box is ticked. The Bright planets last/first visible option is still selected, so we can see that Mercury will be highest in the morning sky and just fading into dawn twilight at 05:42 am local time in Sydney, Australia on 7 February. As before, use the plus/minus hour and minute buttons to step forward/backward in time such that the Local Date & Time window displays the Sydney time of 05:42 am. All done! Now we can examine the observational data in the planetary data table.

The Bright planets last/first visible option is still selected, so we can see that Mercury will be highest in the morning sky and just fading into dawn twilight at 05:42 am local time in Sydney, Australia on 7 February. As before, use the plus/minus hour and minute buttons to step forward/backward in time such that the Local Date & Time window displays the Sydney time of 05:42 am. All done! Now we can examine the observational data in the planetary data table. We can see that on 7 February in Sydney, Mercury rises at 04:24 am local time and the Sun rises at 06:22 am local time. At 05:42 am when the sky is not so bright as to render planet Mercury invisible in a clear sky, yet late enough for the innermost planet to reach its highest in twilight, we see that Mercury is +15 degrees high in the east-southeast — in other words, three times higher in Sydney’s sky compared to Rome for the same level of dawn twilight!

We can see that on 7 February in Sydney, Mercury rises at 04:24 am local time and the Sun rises at 06:22 am local time. At 05:42 am when the sky is not so bright as to render planet Mercury invisible in a clear sky, yet late enough for the innermost planet to reach its highest in twilight, we see that Mercury is +15 degrees high in the east-southeast — in other words, three times higher in Sydney’s sky compared to Rome for the same level of dawn twilight!

Furthermore, we can see that Mercury rises almost a full two hours before the Sun as seen from Sydney, NSW on 7 February 2016, whereas in Rome the innermost planet rises about 1⅓ hours prior to sunrise. The reason for the difference? Well, the angle that the ecliptic makes with the morning horizon in February is steeper in Australia compared to Italy, giving Southern Hemisphere observers a distinct advantage for currently viewing all five bright naked-eye planets in the morning sky.

Inside the magazine

Find out more about observing the Sun, Moon and planets in the February 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.