In a research paper just published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, an international team of astronomers describe surprising findings in their observations of the parent star, which is called HD 100546 or KR Muscae, 325 light-years away in the far southern constellation Musca.

Lead author Dr. Ignacio Mendigutía, from the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Leeds, said: “Nobody has ever been able to probe this close to a star that is still forming and which also has at least one planet so close in.

“We have been able to detect for the first time emission from the innermost part of the disc of gas that surrounds the central star. Unexpectedly, this emission is similar to that of ‘barren’ young stars that do not show any signs of active planet formation.”

To observe this distant system, the astronomers used the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), which is based in an observatory in Chile. The VLTI combines the observing power of four 8.2-metre-wide telescopes and can make images as sharp as that of a single telescope that is 130 metres in diameter.

Professor Rene Oudmaijer, a co-author of the study, also from the University’s School of Physics and Astronomy, said: “Considering the large distance that separates us from the star (325 light-years), the challenge was similar to trying to observe something the size of a pinhead from 100 kilometres away.”

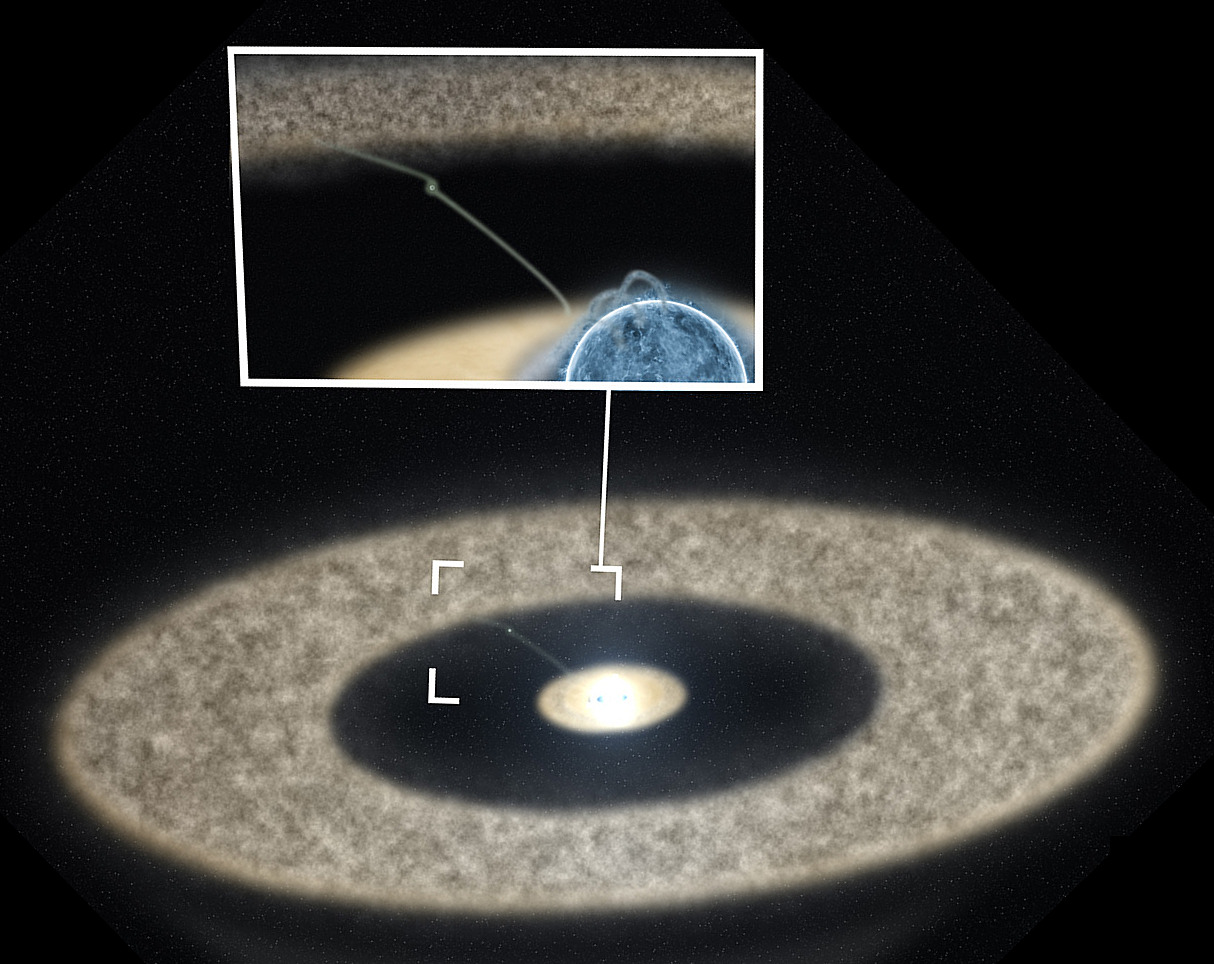

Dr. Mendigutía said: “More interestingly, the disc exhibits a gap that is devoid of material. This gap is very large, about 10 times the size of the space that separates the Sun from the Earth. The inner disc of gas could only survive for a few years before being trapped by the central star, so it must be continuously replenished somehow.

“We suggest that the gravitational influence of the still-forming planet — or possibly planets — in the gap could be boosting a transfer of material from the gas-rich outer part of the disc to the inner regions.”

Systems such as HD 100546 which are known to have both a planet and a gap in the proto-planetary disc are extremely rare. The only other example that has been reported is of a system in which the gap in the disc is ten times further out from the parent star than the one in the new study.

“With our observations of the inner disc of gas in the HD 100546 system, we are beginning to understand the earliest life of planet-hosting stars on a scale that is comparable to our solar system,” concludes Professor Oudmaijer.