NASA made a final attempt to contact the Opportunity Mars rover 12 February, heard no response and then reluctantly bid the robotic geologist farewell with a recording of jazz singer Billie Holiday crooning “I’ll be seeing you.” NASA managers then officially declared the spacecraft lost, eight months after losing contact during a global dust storm, bringing a remarkable 15-year mission to an end.

Designed to operate in the harsh martian environment for just 90 days and to rove at least one kilometre (1,100 yards), Opportunity exceeded NASA’s wildest expectations, covering 45 kilometres (28 miles) since landing on Meridiani Planum on 24 January 2004.

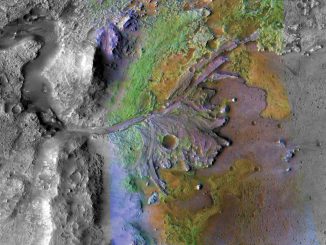

The six-wheeled robot sent back 217,000 pictures, carried out detailed inspections of more than 120 rocks using spectrometers and a microscopic imager, found hematite, a mineral that forms in water, at its landing site and found clear evidence of a watery past at its final resting place, a region near the rim of Endeavour Crater known as Perseverance Valley.

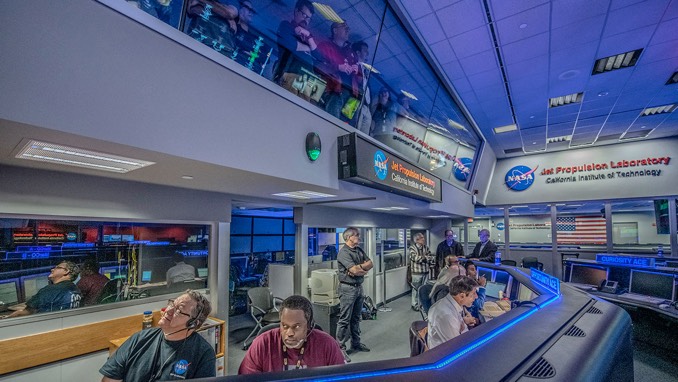

“I cannot think of a more appropriate place for Opportunity to endure on the surface of Mars than one called Perseverance Valley,” said Michael Watkins, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The records, discoveries and sheer tenacity of this intrepid little rover is testament to the ingenuity, dedication, and perseverance of the people who built and guided her.”

Launched on 7 July 2003, Opportunity bounced to an airbag-assisted landing on 24 January 2004, three weeks after a twin rover, Spirit, landed in Gusev Crater on the other side of Mars. The two rovers confirmed water once flowed and pooled on the surface of the red planet, giving planetary geologists their strongest clues yet that Mars once hosted a habitable environment.

“When you combine the discoveries of Opportunity and Spirit, they showed us that ancient Mars was a very different place from Mars today, which is a cold, dry, desolate world,” said Steve Squyres, the mission’s principal investigator. “But if you look to its ancient past, you find compelling evidence for liquid water below the surface and liquid water at the surface.”

Spirit got trapped in deep sand in 2010 and eventually ceased operation. But Opportunity continued to creep across the barren surface, eventually making its way to the edge of Endeavour Crater, an eroded 22-kilometre-wide (14 mile) impact depression. Then in June last year, a global dust storm boiled up, quickly clouding the martian atmosphere and sharply reducing the sunlight reaching Opportunity’s solar panels.

As the opacity of the sky climbed to record levels, the solar cells were unable to keep the rover’s batteries charged and contact was lost on 10 June 2018. Engineers expected the rover to power back up when the sky finally cleared and either attempt to contact Earth or respond to commands sent up from JPL “in the blind.”

But despite their best efforts, flight controllers never heard a response.

“Back in June, we were afflicted by a historic global dust storm on Mars, it just blackened the skies over the rover and starved the rover for energy and the rover went silent,” said John Callas, the project manager at JPL, said during a 13 February news briefing.

“We tried valiantly over these last eight months to try to recover the rover, to get some signal from it, we listened every single day with the Deep space Network, and we sent over a thousand recovery commands, trying to exercise every possibility of getting a signal from the rover.”

The team held out hope that the windy season on Mars might blow accumulated dust from the arrays and permit battery charging, but after a final round of commands, “we heard nothing,” Callas said.

“And so, it comes time to say goodbye,” he said. “But we want to remember the 14-and-a-half years of phenomenal exploration. This was a 90-day mission, and we were so excited by just having three months to explore the planet with just a kilometre of capability. But 14-and-a-half years later, and 45 kilometres of odometry, we’ve done phenomenal things, we’ve greatly expanded our understanding of the red planet.”