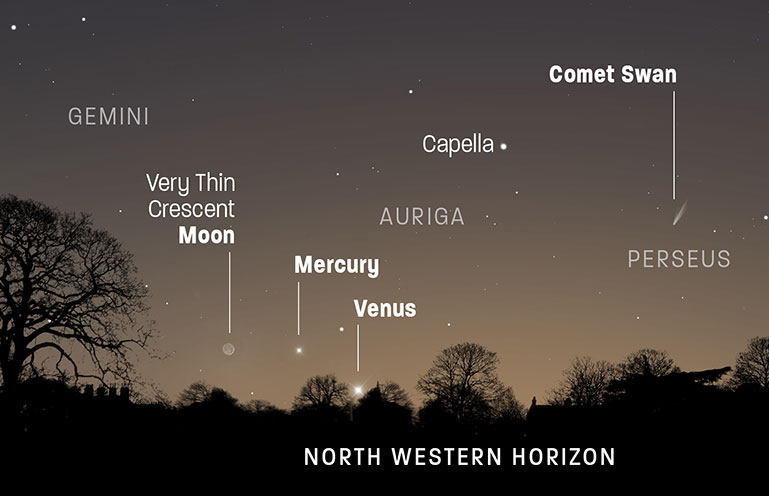

Look to the north-west on the evening of Friday 22 May, soon after sunset, to enjoy a spectacular coming together of brilliant Venus and shy and elusive Mercury. The planetary pair are separated in the sky by just 1.3 degrees (77 arcminutes), which is just over two full-Moon diameters. (Another easy-to-demonstrate method of gauging how far this is, is that a finger held out at arm’s length covers approximately one degree.) Given clear skies, with a few caveats, this exciting event can be enjoyed even from light-polluted towns and cities.

The one fly in the ointment is that the conjunction occurs at an altitude of less than 10 degrees, so you’ll need to have a horizon from the west-north-west around to the north-west (azimuth 290 to 315 degrees; check your smartphone’s compass) that’s free from obscuring buildings and trees. If you can secure a good view, then this event should be readily visible with the naked eye, but have a pair of binoculars or a small telescope, operating at a low magnification, to hand in case the early evening is hazy. Sunset in London occurs shortly before 9pm BST (20:00 UT), at 9.14pm in Manchester and just after 9.30pm in Edinburgh. Your smartphone’s weather app can give your local sunset time.

If you have to use binoculars to view the conjunction, then make absolutely sure that the Sun has set below the horizon at your location before sweeping across the sky. If the Sun enters the field of view of any optical aid that you are using, its heat and light can cause catastrophic damage to your eyesight.

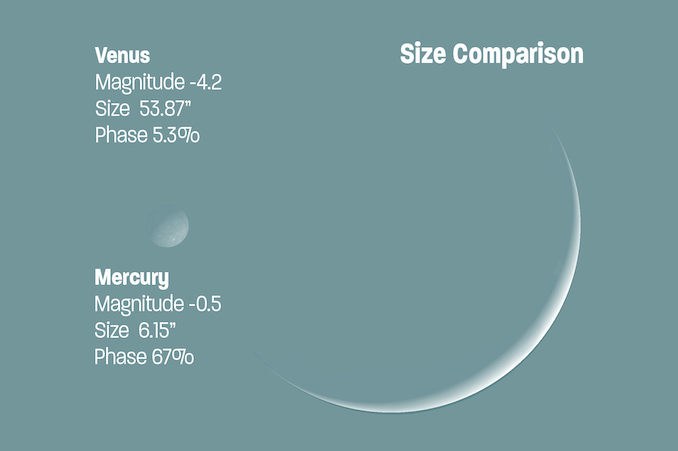

Venus will be the first astronomical object to appear in the deepening twilight. Even casual stargazers can’t have failed to notice the blazing ‘evening star’ that has recently seemed an almost permanent fixture in the post-sunset western sky, especially given the fine weather and clear skies most of the UK has been enjoying. The more committed observers will have noticed that the gloss has been coming off Venus’ brilliance as May has progressed, with the planet sinking lower in the sky and its brightness dimming somewhat. Having said this, Venus is still a blazing beacon, shining at magnitude –4.2.

It shouldn’t be too long into the evening before Mercury appears alongside Venus, placed to Venus’ left at roughly the same altitude. Mercury has been on the scene for about a week now, itself shining significantly brighter than any star visible from UK shores at this time of year, as it has been climbing steadily away from the north-western horizon. This evening it shines at magnitude –0.5.

The end of civil twilight (when the Sun lies six degrees below the horizon) usually signals the appearance of the brighter stars. In London, this occurs at about 9.40pm BST (20.40 UT) and at 10pm and 10.25pm, from Manchester and Edinburgh, respectively. The planetary pair lie at an altitude just short of eight degrees as seen from London, and just over six and seven degrees as seen from Edinburgh and Manchester, respectively.

During any moments of steady seeing (often fleeting at such a low elevation), it might be possible to glean Venus’ extremely thin crescent disc through a pair of binoculars. Its elongation from the Sun is only 20 degrees and so it exhibits just a 5.3 per cent-illuminated phase some 53 arcminutes in size. A small telescope would be a better bet to see this, as well as resolving Mercury’s 67 per cent-illuminated gibbous phase.

Experienced observers can observe this conjunction in broad daylight, as Venus and Mercury are actually at their closest of 0.9 degree (53 arcminutes) at around 9am BST (08:00 UT). At this time, the pair lie about 27 degrees above the eastern horizon from London, and culminate due south at an advantageous 65-degree altitude at around 2.15pm BST, when their separation has widened to nearly 56 arcminutes. Viewing astronomical objects that are close to the Sun in broad daylight is fraught with danger, given the risk of damaging your eyes by looking at the Sun, so this is not recommended for casual or inexperienced observers.

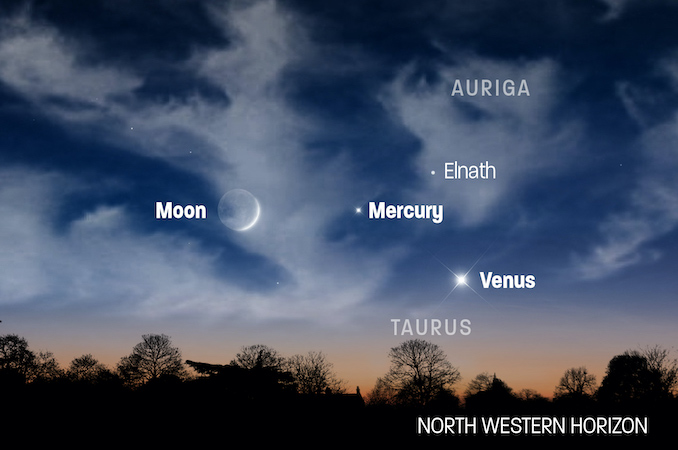

If you are clouded out or can’t be free to observe this conjunction, then two evenings later, on Sunday 24 May, look out for when the young crescent Moon muscles in on the scene. It appears above five degrees to the left of Mercury, which is now separated from Venus by just over five degrees.

Venus now rapidly departs the evening sky on its way to inferior conjunction (between us and the Sun) on 3 June. It’s been a memorable evening apparition and, in what’s a great year for Venus fanciers, the planet returns as a blazing ‘morning star’ in July, for what promises to be a splendid morning apparition that lasts almost until the end of 2020.

Mercury makes further strides in evening visibility to put on a fine evening apparition, centred on a greatest eastern elongation from the Sun on 4 June.

It’s not all that common to see the two innermost, or so-called ‘inferior’ planets, come this close together, so make the most of it should the sky be clear for you.