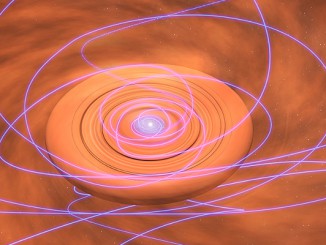

Measurements of T-Tauri circumstellar discs provide important tests for theories of planet formation and migration. Near-infrared results, for example, sample the hotter temperature dust grains, and can reveal the presence of gaps in the disc (perhaps cleared by massive planets) when an expected ring of warm dust around the star is not detected. Astronomers during the past few decades have been able to use infrared space telescopes like NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope to probe T-Tauri discs, but there are still many puzzles, in particular about the mechanisms responsible for the accretion, the subsequent dissipation of material, and the evolutionary ages when these processes occur.

CfA astronomer Philip Cargile was a member of a team of seven scientists studying the evolution of these stars and their discs. They took detailed optical observations (including spectra) of a sample of twenty-five X-ray selected T-Tauri stars in two nearby star-forming clouds to derive their ages and stellar masses. They find that most of the sources in one cloud are between about five and six million year old; a couple turn out to be more like twenty-five million years old and can now be excluded from the T-Tauri class. In the other cloud, most of the sources are younger than about ten million years. The results agree well with theoretical models and other observations. Perhaps more usefully, the results help to identify true T-Tauri stars with discs that would be suitable for imaging observations with a new generation of large telescopes.

This research appears in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.