The distance between the galactic cosmic rays’ point of origin and Earth is limited by the survival of a very rare type of cosmic ray that acts like a tiny clock. The cosmic ray is a radioactive isotope of iron, 60Fe, which has a half life of 2.6 million years. In that time, half of these iron nuclei decay into other elements.

In the 17 years CRIS has been in space, it detected about 300,000 galactic cosmic-ray nuclei of ordinary iron, but just 15 of the radioactive 60Fe.

“Our detection of radioactive cosmic-ray iron nuclei is a smoking gun indicating that there has been a supernova in the last few million years in our neighbourhood of the galaxy,” said Robert Binns, research professor of physics in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and lead author on the paper published online in Science on 21 April 2016.

“The new data also show the source of galactic cosmic rays is nearby clusters of massive stars where supernova explosions occur every few million years,” said Martin Israel, professor of physics at Washington University and a co-author on the paper.

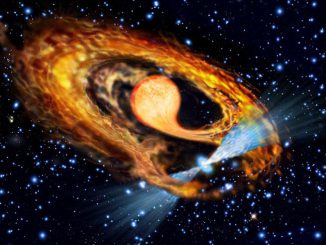

The radioactive iron is believed to be produced in core-collapse supernovae, violent explosions that mark the death of massive stars, which occur primarily in clusters of massive stars called OB associations.

There are more than 20 such associations close enough to Earth to be the source of the cosmic rays, including subgroups of the nearby Scorpius and Centaurus constellations, such as Upper Scorpius (83 stars), Upper Centaurus-Lupus (134 stars) and Lower Centaurus-Crux (97 stars). Because of their size and proximity, these are the likely sources of the radioactive iron nuclei CRIS detected, the scientists said.

The 60Fe results add to a growing body of evidence that galactic cosmic rays are created and accelerated in OB associations.

Earlier CRIS measurements of nickel and cobalt isotopes show there must be a delay of at least 100,000 years between creation and acceleration of galactic cosmic-ray nuclei, Binns said.

This time lag also means that the nuclei synthesised in a supernova are not accelerated by that supernova but by the shock wave from a second nearby supernova, Israel said, one that occurs quickly enough that a substantial fraction of the 60Fe from the first supernova has not yet decayed.

Together, these time constraints mean the second supernova must occur between 100,000 and a few million years after the first supernova. Clusters of massive stars are one of the few places in the universe where supernovae occur often enough and close enough together to bring this off.

“So our observation of 60Fe lends support to the emerging model of cosmic-ray origin in OB associations,” Israel said.

Corroborating Evidence?

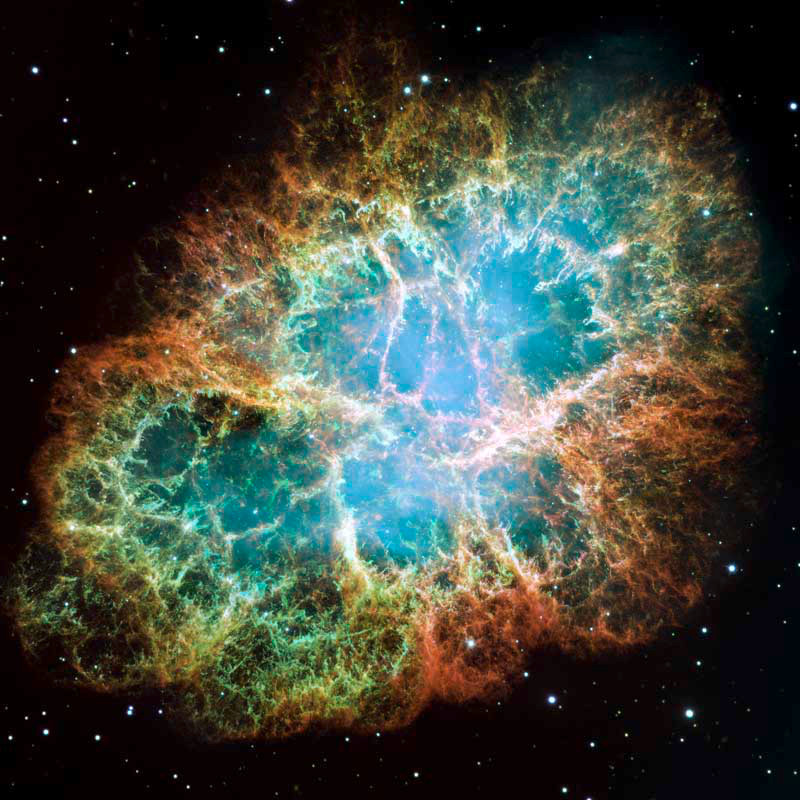

Although the supernovae in a nearby OB association that created the 60Fe CRIS observed happened long before people were around to observe suddenly brightening stars (novae), they also may have left traces in Earth’s oceans and on the Moon.

In 1999, astrophysicists proposed that a supernova explosion in Scorpius might explain the presence of excessive radioactive iron in 2.2 million-year-old ocean crust. Two research papers recently published in Nature bolster this case. One research group examined 60Fe deposition worldwide and argued that there might have been a series of supernova explosions, not just one. The other simulated by computer the evolution of Scorpius-Centaurus association in an attempt to nail down the sources of the 60Fe.

Lunar samples also show elevated levels of 60Fe consistent with supernova debris arriving at the Moon about 2 million years ago. And here, too, there is recent corroboration. A paper just published in Physical Review Letters describes an analysis of nine core samples brought back by the Apollo crews.