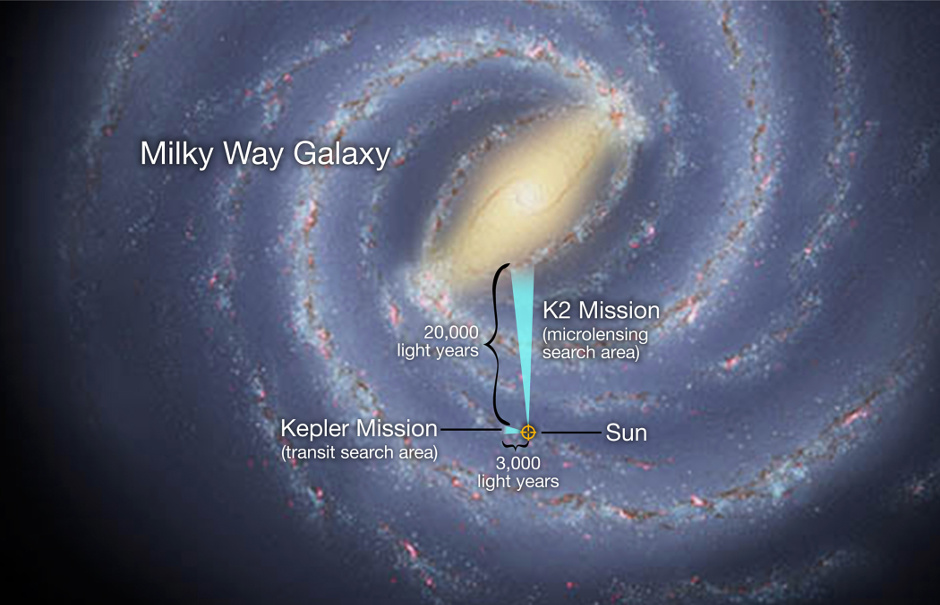

The majority of these exoplanets have been found snuggled up to their host star completing an orbit (or year) in hours, days or weeks, while some have been found orbiting as far as Earth is to the Sun, taking one Earth year to circle. But, what about those worlds that orbit much farther out, such as Jupiter and Saturn, or, in some cases, free-floating exoplanets that are on their own and have no star to call home? In fact, some studies suggest that there may be more free-floating exoplanets than stars in our galaxy.

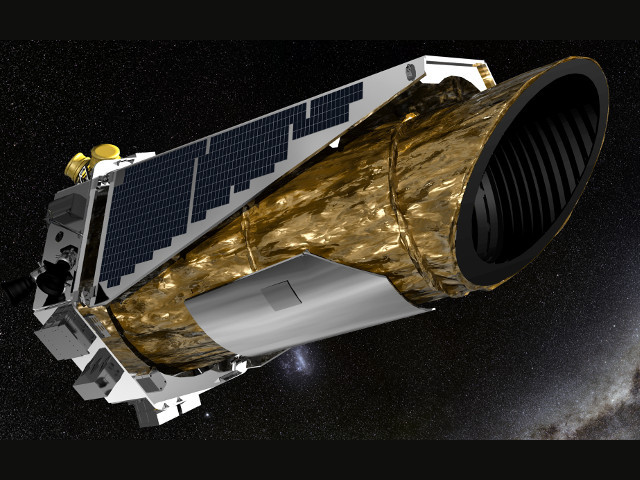

This week, NASA’s K2 mission, the repurposed mission of the Kepler space telescope, and other ground-based observatories, have teamed up to kick-off a global experiment in exoplanet observation. Their mission: survey millions of stars toward the centre of our Milky Way galaxy in search of distant stars’ planetary outposts and exoplanets wandering between the stars.

While today’s planet-hunting techniques have favoured finding exoplanets near their sun, the outer regions of a planetary system have gone largely unexplored. In the exoplanet detection toolkit, scientists have a technique well suited to search these farthest outreaches and the space in between the stars. This technique is called gravitational microlensing.

Gravitational microlensing

For this experiment, astronomers rely on the effect of a familiar fundamental force of nature to help detect the presence of these far out worlds — gravity. The gravity of massive objects such as stars and planets produces a noticeable effect on other nearby objects.

But gravity also influences light, deflecting or warping the direction of light that passes close to massive objects. This bending effect can make gravity act as a lens, concentrating light from a distant object, just as a magnifying glass can focus the light from the Sun. Scientists can take advantage of the warping effect by measuring the light of distant stars, looking for a brightening that might be caused by a massive object, such as a planet, that passes between a telescope and a distant background star. Such a detection could reveal an otherwise hidden exoplanet.

“The chance for the K2 mission to use gravity to help us explore exoplanets is one of the most fantastic astronomical experiments of the decade,” said Steve Howell, project scientist for NASA’s Kepler and K2 missions at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “I am happy to be a part of this K2 campaign and look forward to the many discoveries that will be made.”

This phenomenon of gravitational microlensing — “micro” because the angle by which the light is deflected is small — is the effect for which scientists will be looking during the next three months. As an exoplanet passes in front of a more distant star, its gravity causes the trajectory of the starlight to bend, and in some cases results in a brief brightening of the background star as seen by the observatory.

The lensing events caused by a free-floating exoplanet last on the order of a day or two, making the continuous gaze of the Kepler spacecraft an invaluable asset for this technique.

“We are seizing the opportunity to use Kepler’s uniquely sensitive camera to sniff for planets in a different way,” said Geert Barentsen, research scientist at Ames.

The ground-based observatories will record simultaneous measurements of these brief events. From their different vantage points, space and Earth, the measurements can determine the location of the lensing foreground object through a technique called parallax.

To understand parallax, extend your arm and hold up your thumb. Close one eye and focus on your thumb and then do the same with the other eye. Your thumb appears to move depending on the vantage point. For humans to determine distance and gain depth perception, the vantage points, our eyes, use parallax.

Flipping the spacecraft

The Kepler spacecraft trails Earth as it orbits the Sun and is normally pointed away from Earth during the K2 mission. But this orientation means that the part of the sky being observed by the spacecraft cannot generally be observed from Earth at the same time, since it is mostly in the daytime sky.

This alignment will also yield a viewing opportunity of Earth and the Moon as they cross the spacecraft’s field of view. On 14 April 14 at 7:50pm BST (18:50 UT), Kepler will record a full frame image. The result of that image will be released to the public archive in June once the data has been downloaded and processed. Kepler measures the change in brightness of objects and does not resolve color or physical characteristics of an observed object.

Observing from Earth

To achieve the objectives of this important path-finding research and community exercise in anticipation of WFIRST, approximately two-dozen ground-based observatories on six continents will observe in concert with K2. Each will contribute to various aspects of the experiment and will help explore the distribution of exoplanets across a range of stellar systems and distances.

These results will aid in our understanding of planetary system architectures, as well as the frequency of exoplanets throughout our galaxy.

For a complete list of participating observatories, reference the paper that defines the experiment: Campaign 9 of the K2 Mission.

During the roughly 80-day observing period or campaign, astronomers hope to discover more than 100 lensing events, ten or more of which may have signatures of exoplanets occupying relatively unexplored regimes of parameter space.