Comets are known to be a mixture of dust and ice, and if fully compact, they would be heavier than water. However, previous measurements have shown that some of them have extremely low densities, much lower than that of water ice. The low density implies that comets must be highly porous.

But is the porosity because of huge empty caves in the comet’s interior or it is a more homogeneous low-density structure?

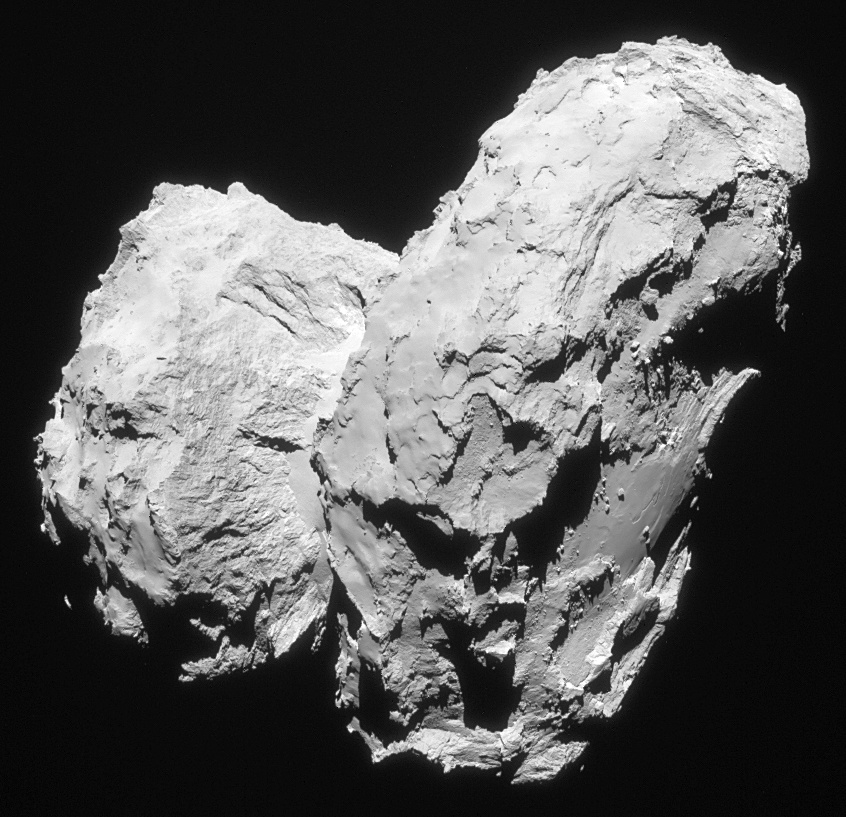

In a new study, published in this week’s issue of the journal Nature, a team led by Martin Pätzold, from Rheinisches Institut für Umweltforschung an der Universität zu Köln, Germany, have shown that Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is also a low-density object, but they have also been able to rule out a cavernous interior.

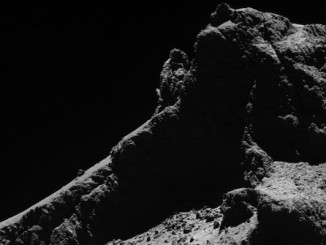

This result is consistent with earlier results from Rosetta’s CONSERT radar experiment showing that the double-lobed comet’s ‘head’ is fairly homogenous on spatial scales of a few tens of metres.

The most reasonable explanation then is that the comet’s porosity must be an intrinsic property of dust particles mixed with the ice that make up the interior. In fact, earlier spacecraft measurements had shown that comet dust is typically not a compacted solid, but rather a ‘fluffy’ aggregate, giving the dust particles high porosity and low density, and Rosetta’s COSIMA and GIADA instruments have shown that the same kinds of dust grains are also found at 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Pätzold’s team made their discovery by using the Radio Science Experiment (RSI) to study the way the Rosetta orbiter is pulled by the gravity of the comet, which is generated by its mass.

The effect of the gravity on the movement of Rosetta is measured by changes in the frequency of the spacecraft’s signals when they are received at Earth. It is a manifestation of the Doppler effect, produced whenever there is movement between a source and an observer, and is the same effect that causes emergency vehicle sirens to change pitch as they pass by.

ESA’s Rosetta mission is the first to perform this difficult measurement for a comet.

“Newton’s law of gravity tells us that the Rosetta spacecraft is basically pulled by everything,” says Martin Pätzold, the principal investigator of the RSI experiment.

“In practical terms, this means that we had to remove the influence of the Sun, all the planets — from giant Jupiter to the dwarf planets — as well as large asteroids in the inner asteroid belt, on Rosetta’s motion, to leave just the influence of the comet. Thankfully, these effects are well understood and this is a standard procedure nowadays for spacecraft operations.”

Next, the pressure of the solar radiation and the comet’s escaping gas tail has to be subtracted. Both of these ‘blow’ the spacecraft off course. In this case, Rosetta’s ROSINA instrument is extremely helpful as it measures the gas that is streaming past the spacecraft. This allowed Pätzold and his colleagues to calculate and remove those effects too.

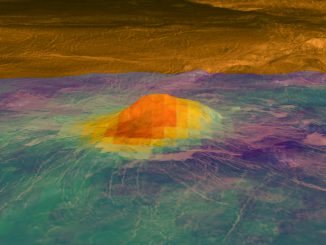

Whatever motion is left is due to the comet’s mass. For Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, this gives a mass slightly less than 10 billion tons. Images from the OSIRIS camera have been used to develop models of the comet’s shape and these give the volume as around 18.7 km3, meaning that the density is 533 kg/m3.

Extracting the details of the interior was only possible through a piece of cosmic good luck.

Given the lack of knowledge of the comet’s activity, a cautious approach trajectory had been designed to ensure the spacecraft’s safety. Even in the best scenario, this would bring Rosetta no closer than 10 kilometres.

Unfortunately, prior to 2014, the RSI team predicted that they needed to get closer than 10 kilometres to measure the internal distribution of the comet. This was based on ground-based observations that suggested the comet was round in shape. At 10 kilometres and above, only the total mass would be measurable.

Then the comet’s strange shape was revealed as Rosetta drew nearer. Luckily for RSI, the double-lobed structure meant that the differences in the gravity field would be much more pronounced, and therefore easier to measure from far away.

“We were already seeing variations in the gravity field from 30 kilometres away,” says Pätzold.

When Rosetta did achieve a 10-kilometre orbit, RSI was able to gather detailed measurements. This is what has given them such high confidence in their results, and it could get even better.

In September, Rosetta will be guided to a controlled impact on the surface of the comet. The maneuver will provide a unique challenge for the flight dynamics specialists at ESA’s European Space Operations Center (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany. As Rosetta gets nearer and nearer the complex gravity field of the comet will make navigating harder and harder. But for RSI, its measurements will increase in precision. This could allow the team to check for caverns just a few hundred metres across.