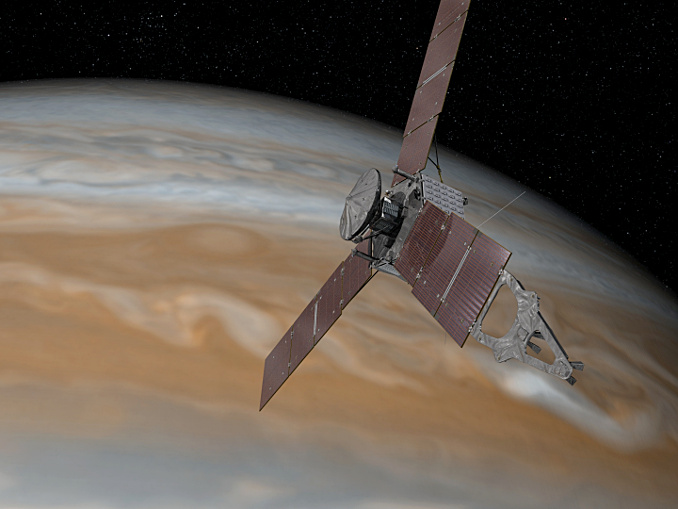

“We have over five years of spaceflight experience and only 10 days to Jupiter orbit insertion,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “It is a great feeling to put all the interplanetary space in the rearview mirror and have the biggest planet in the solar system in our windshield.”

On 11 June, Juno began transmitting to and receiving data from Earth around the clock. This constant contact will keep the mission team informed on any developments with their spacecraft within tens of minutes of it occurring. On 20 June, the protective cover that shields Juno’s main engine from micrometeorites and interstellar dust was opened, and the software program that will command the spacecraft through the all-important rocket burn was uplinked.

One of the important near-term events remaining on Juno’s pre-burn itinerary is the pressurisation of its propulsion system on 28 June. The following day, all instrumentation not geared toward the successful insertion of Juno into orbit around Jupiter on 4 July will be turned off.

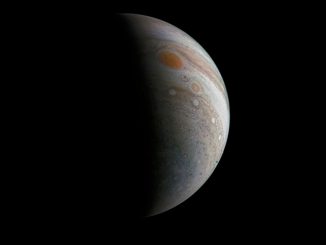

“If it doesn’t help us get into orbit, it is shut down,” said Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “That is how critical this rocket burn is. And while we will not be getting images as we make our final approach to the planet, we have some interesting pictures of what Jupiter and its moons look like from five-plus million miles away.”

JunoCam is an outreach instrument — its inclusion in this mission of exploration was to allow the public to come along for the ride with Juno. JunoCam’s optics were designed to acquire high-resolution views of Jupiter’s poles while the spacecraft is flying much closer to the planet. Juno will be getting closer to the cloud tops of the planet than any mission before it, and the image resolution of the massive gas giant will be the best ever taken by a spacecraft.

All of Juno’s instruments, including JunoCam, are scheduled to be turned back on approximately two days after achieving orbit. JunoCam images are expected to be returned from the spacecraft for processing and release to the public starting in late August or early September.

“This image is the start of something great,” said Bolton. “In the future we will see Jupiter’s polar auroras from a new perspective. We will see details in rolling bands of orange and white clouds like never before, and even the Great Red Spot.

More information on the Juno mission is available at: http://www.nasa.gov/juno