Amid flame and smoke, the Hubble Space Telescope blasted off the launch pad aboard the space shuttle Discovery 30 years ago today, ushering in a new era for astronomy that has transformed our understanding of the Universe around us.

Yet just a month after its launch, few people would have believed that the $1.5 billion space telescope would have lasted three years, never mind thirty. An error in the construction of Hubble’s 2.4-metre main mirror had seen it sculpted to an incorrect specification. It was a mere two microns – that’s two-millionths of a metre – out of shape, but that was enough to result in an acute case of spherical aberration. In other words, as the first images back from Hubble attested to, the space telescope was born short-sighted, capable or bringing to focus only 15 per cent of the light that it collected. What should have been crystal-clear images of stars, nebulae and galaxies were fuzzy, indistinct, and absent of all the detail that Hubble had been designed to see.

In what was probably NASA’s greatest moment since the Apollo programme, the space agency turned around this catastrophic situation and rescued Hubble from ignominy. Seven astronauts, having spent months training for five risky and complex spacewalks, undertook a daring mission aboard the space shuttle Endeavour in December 1993 to install ‘glasses’ – the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement, or COSTAR – on Hubble, as well as replace several instruments. Their rescue mission was a success, and the Hubble Space Telescope became a triumph not only for NASA, but for the entire astronomical world.

Suddenly, scientists really were able to probe the deepest depths of the cosmos and see things no one had ever seen before. What they found with Hubble was often beyond anybody’s wildest imagination.

Hubble’s edge

What gives the Hubble Space Telescope the edge is the fact that it resides in space, 568-kilometres high above the surface, and the vast bulk of the Earth’s atmosphere. As the nursery rhyme reminds us, when we look at the stars from the ground they appear to twinkle. It’s an optical effect, brought about by the shifting currents within our atmosphere, but it limits the potential maximum resolution of any given telescope on Earth. There are now ways around this for most modern professional observatories, by using laser beams to create an artificial guide star for adaptive optics to track and counteract most of the twinkling, but by being in space, Hubble can avoid this problem entirely. Plus, Hubble has ultraviolet and near-infrared capabilities, and these are wavelengths of light that would otherwise be absorbed by our atmosphere. As such, Hubble’s vision is greater than any current ground-based telescope.

Two images in particular, which came in quick succession in 1995, showcased Hubble’s ability to present the Universe with a clarity never experienced before, and to see deeper than any telescope had done previously.

Technicolour towers

The first was the famous ‘Pillars of Creation’, which are three towering spires of molecular gas, each several light years long, at the heart of the Eagle Nebula, which is about 6,500 light years away. The image is astounding for numerous reasons. The detail seen in the Pillars, where stars are being born, was unlike anything else seen at the time. Sculpted by the harsh ultraviolet light of newborn stars ionising the gas and causing it to ‘photo-evaporate’, the image showed, for the first time, this process in action. The spectacular image also showcased the Hubble colour palette, a technicolour mix of red, green and blues representing light from sulphur-II, hydrogen-alpha and oxygen-III emission. More importantly, the Pillars of Creation gave the public a view of the Universe that even outmatched the grandeur of science fiction, cementing Hubble’s reputation as a household name, now for all the best reasons.

Deep Field, even deeper meaning

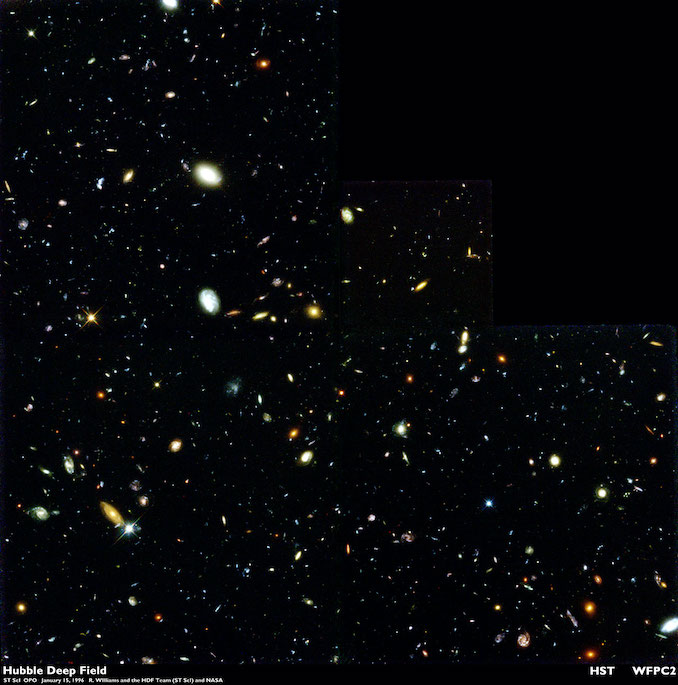

The second image might not have had the aesthetic beauty of the Pillars of Creation, but for profundity it exceeded it. The Hubble Deep Field was our most intense look into the distant, early Universe at the time. The space telescope gazed at a singular patch of sky, just 2.6 arcminutes across, over ten days to record 1,500 faraway galaxies in that tiny region of the sky, some whose light set off on its journey as long ago as 12 billion years in the past, less than two billion years after the Big Bang. The Hubble Deep Field, and its successor, 2004’s Hubble Ultra Deep Field (which itself was enhanced in 2013 to become the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field), take us back to near the dawn of time, and the growth of the first galaxies. In a way, it’s like comparing a picture of yourself as an adult with a photo of yourself as a toddler. The Deep Field speaks to us of our cosmic history through deep time, as we look back towards the beginning of everything.

Exploring new frontiers

In the quarter of a century since those two images were taken, the Hubble Space Telescope has continued to scale new heights, but nothing has perhaps been quite the watershed moment that those two images provided. They, and Hubble, changed what we thought was possible in astronomy and have opened our eyes to new frontiers. In almost every major astronomical advance over the past three decades, Hubble has played a role, whether it be the study of the development of galaxies and their black holes, the science of exoplanets, the quest to identify dark matter and dark energy, and the aim of understanding how stars are born, live and die.

Despite now holding ‘veteran observatory’ status, the Hubble Space Telescope still has lots of life left in it. It’s got enough gyroscopes still functioning to keep pointing accurately, its cameras and spectrographs all still function, and there’s still much science to be conducted with it. With a little luck and care, it will survive to see its fortieth anniversary, and based on what Hubble has accomplished over the past 30 years, there are plenty of reasons to feel excited about what the next 10 years may have in store.

Our May issue is now available to order in print or digital versions and includes part 2 of our special coverage to mark the 30th anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope.